Walgreens’ lost decade: How M&A mania and retail neglect shrunk a $100 billion giant to a $10 billion private equity gamble

As Walgreens exits Wall Street after 98 years, its new owners face a daunting turnaround. Will a renewed focus on its pharmacies and more financial discipline be enough?

In hindsight, it was an exchange that encapsulated years of shopper frustration.

On an earnings call in January, a Wall Street analyst asked Walgreens Boots Alliance CEO Tim Wentworth about his efforts to ease the strain that the U.S. drugstore chain’s security measures were putting on its sales. As millions of American shoppers know, and many deeply resent, a great many items in a typical Walgreens are locked up behind glass—obtainable only with help from a clerk. (And, by the way, good luck finding a clerk.)

Wentworth responded that countering shoplifting was like “hand-to-hand combat.” He then made a comment that earned him countless headlines: “When you lock things up, you don’t sell as many of them. We’ve kind of proven that pretty conclusively.”.

“No sh*t, Sherlock,” was the general flavor of reactions in countless comment sections, as critics noted that the CEO of the company that owns the 8th-largest U.S. retailer ought to have understood that equation intuitively.

Wentworth, a well-regarded executive, went on to explain that the loss to theft was hurting the company’s profit too much, hence the draconian lockdowns. But investors’ annoyance over his answers pointed to Walgreens’ much deeper problems.

In 2024, Walgreens drugstores generated non-pharmacy revenue—called “front-of-store sales” in the industry—of some $27 billion, from items like toothpaste, soda, aspirin and potato chips; and another $89 billion from filling prescriptions and other pharmacy services. Pharmacy has historically had lower margins than front-of-store, and in recent years, under pressure from insurance companies and rivals, those pharmacy margins have only gotten lower. In the old days, front-of-stores’ better profits helped raise overall margins. But alas for Walgreens, its retail business, left on autopilot for years, analysts say, has slipped—and in 2023 and 2024, the company posted a total of $11.7 billion in losses, among the highest totals of any Fortune 500 company.

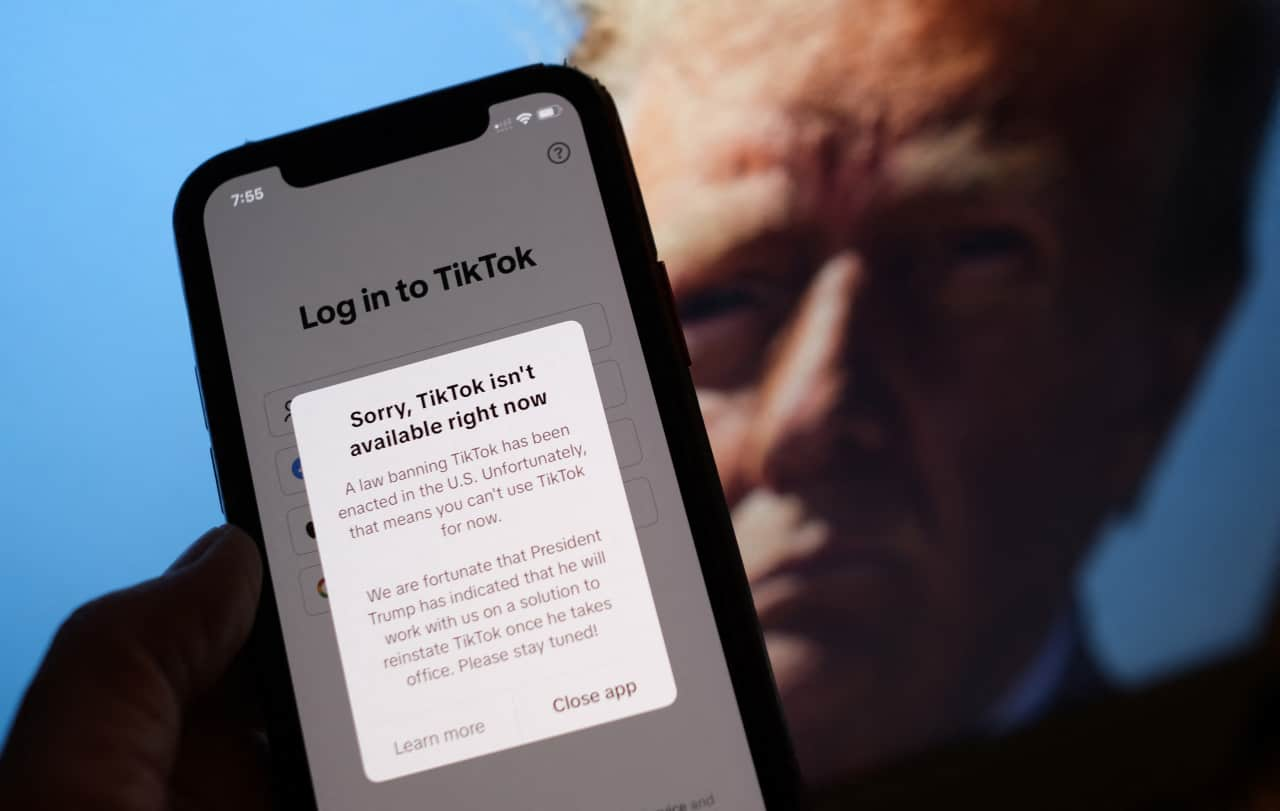

Wentworth will likely soon be spared from having to publicly field any more investor questions. In March, Walgreens Boots Alliance announced that it had reached a deal to be bought by a private equity firm, Sycamore Partners, for $10 billion, in a transaction that will take it off the U.S. stock market after 98 years. The deal is expected to close in late 2025.

For Walgreens, going private is the culmination of an epic fall from grace. A decade ago, it was worth $100 billion, riding high on the buzz of a bold albeit controversial merger. But since then, its failings have sent shares down 91%. The company has been weakened by years of bad deal-making that left it with too many stores; detritus from failed efforts to become a successful player in healthcare; and a heavy debt burden.

In early 2024, Walgreens was removed from the Dow Jones Industrial Average, a sign of its rapidly declining relevance. Another indignity: in January, Walgreens suspended its quarterly dividend, one it had paid without fail for 91 years, to hold on to desperately needed cash.

On the bright side, going private will give the venerable chain’s leaders an opportunity to fix its many problems. Since taking the helm in 2023, Wentworth has repeatedly warned investors that many elements of the company need a time-consuming turnaround—from its tired stores, ill-equipped for the e-commerce era, to shrinking reimbursement rates, to demoralized staff. All that work will be more easily and quickly done away from Wall Street’s klieg lights.

“It’s hard to do under the microscope of quarterly check-ins with the investor community, so hopefully they can get back up there with the hard decisions they’re going to have to make,” says Michael Cherny, an analyst at Leerink Partners, an investment bank focused solely on health care.

Walgreens has in recent years undone, or is preparing to undo, some of its ill-advised acquisitions. It has already taken a $5.8 billion write-down on its acquisition of primary care provider VillageMD. But such changes leave the company extremely reliant on its core drugstore businesses, selling general merchandise and filling prescriptions to get out of the hole it has fallen into. Wentworth has won credit from analysts for his early progress in improving Walgreens’ cost structure, and his willingness to close money-sapping stores. But Wentworth, or whoever becomes CEO if Sycamore brings in someone else, faces a long, tough slog. (Walgreens declined to make Wentworth available for an interview; Sycamore declined to comment.)

“The next few quarters are about laying bricks, not finishing walls, to set the foundation for the company’s next chapter,” Jonathan Palmer, an analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence, wrote in a research note.

A long history, and grand ambitions

Walgreens, the U.S. druggist that is the biggest component of Walgreens Boots Alliance, was founded in 1901 when Chicago pharmacist Charles R. Walgreen bought the store at which he worked. By the time the Great Depression hit, the company was already a 500-store chain with locations far afield from Chicago, many of them anchored by lunch counters whose malted milkshakes and hot meals helped make the chain beloved.

Later, Walgreens pioneered features like drive-through pharmacies and in 1999, an online pharmacy. It also became a front-runner in the pharmacy wars, along with CVS (initially called Consumer Value Stores) and Rite Aid. As these national chains emerged, they absorbed countless local drugstores along the way. By the early 2010s, after years of industry consolidation, CVS and Walgreens were duking it out for the top spot, each with about 10,000 locations at their peak, and Rite Aid a distant third.

By that point, the two behemoths, long interchangeable, were going in different directions. Walgreens believed that its scale and its millions of customers gave it clout with pharmacy benefits managers, or PBMs, which function as a type of go-between, negotiating how patients pay for drugs, what insurers owe drugmakers, and how much pharmacies are reimburses. It believed that clout would only grow if it continued its drugstore pharmacy land grab.

But CVS had already started to pursue ambitions well beyond its drugstore roots. The company bought Caremark, a leading PBM, in 2007 for $21 billion. Seven years later, CVS garnered big headlines when it stopped selling cigarettes and changed its name to CVS Health, making its new orientation unmistakable. It followed that move with several big acquisitions of clinics and specialty pharmacies.

While CVS reinvented itself, Walgreens kept fumbling the ball. In 2011, it overplayed its hand in a dispute with Express Scripts, a major PBM, and lost the business of millions of customers for years. That stoked investor interest in a new catalyst for growth and new management. Enter Italian billionaire Stefano Pessina, the largest shareholder in British druggist chain Alliance Boots.

In 2012, Walgreens bought a minority stake in Alliance Boots; it then bought the rest of it two years later for $10 billion in all. The deal was something of a reverse merger, with Pessina and his posse becoming CEO and top managers, respectively, of the newly minted Walgreens Boots Alliance. The idea was to create the first ever international drugstore chain operator and drug wholesaling company. And the plan might have worked—had it been executed well.

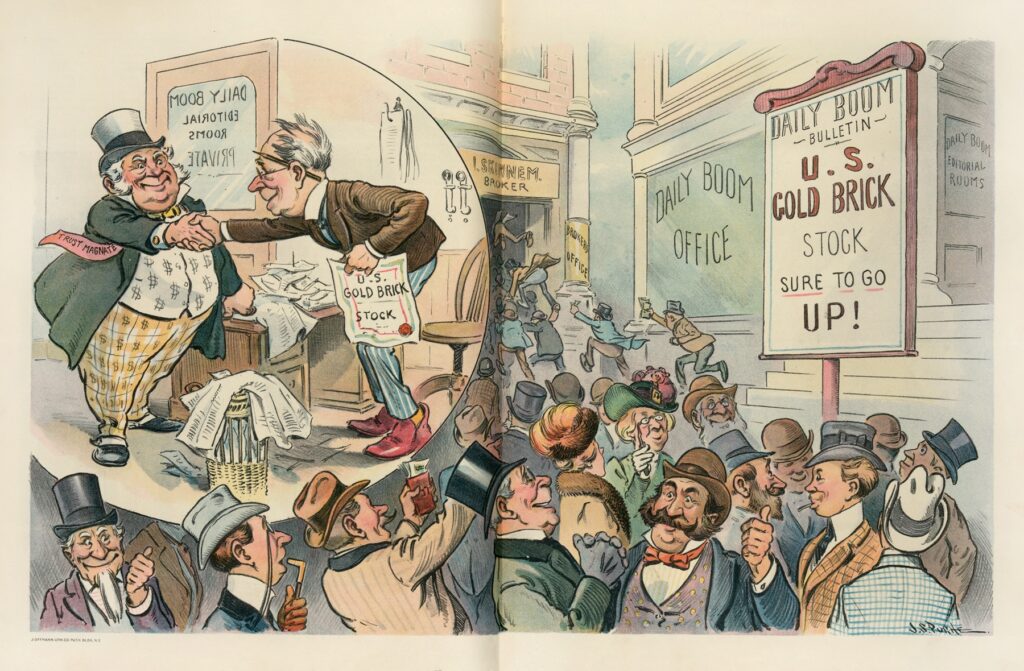

The Bad News Bears of M&A

Pessina, an M&A enthusiast (some might even say addict) was still caught up in the Walgreens vs. CVS race to be the chain with the most stores. Not long after the Boots Alliance merger, he set his eyes on Rite Aid, the third-place pharmacy contender, which had been struggling for years under $3 billion debt stemming from a 2006 deal to buy rival chains Eckerd and Brooks. The interest expense had been impeding Rite Aid from investing in keeping stores enticing enough to keep up with its bigger roles.

In 2015, Walgreens made a bid to buy Rite Aid and its 5,000 stores for $9.4 billion. But in a case of antitrust regulators saving a company from itself, the Federal Trade Commission blocked the deal but ultimately allowed Walgreens to buy only 2,100 stores. The result was a larger Walgreens store footprint—but one with tons of overlap, given the proximity of many Rite Aids to nearby Walgreens.

Walgreens had bragged for years about having the stores on the best corners: Now, it often had two stores within blocks of each other, cannibalizing each other’s sales. Last year, Wentworth announced Walgreens would close 1,200 stores out of 8,700. While he didn’t specify which ones had been Rite Aid locations, the store closures announcement was a tacit admission that much of the $4 billion Walgreens had plunked down for 40% of Rite Aid’s fleet had been a waste of money.

Even as Walgreens expanded its store footprint, some analysts were bemoaning the lack of innovation at and updating of its existing fleet. When Walgreens bought Boots, a chain beloved in Great Britain for sleek stores with cool beauty areas and for its No. 7 store brand, it touted how it could borrow from Boots’ playbook. But that never took place. “It was a massive missed opportunity to elevate Walgreens,” says Neil Saunders, managing director of GlobalData. He also sees Walgreens inertia as contributing to it losing much of its beauty industry market share to Ulta Beauty.

For both Walgreens and CVS, retail seemed to become an afterthought by the late 2010s. For both chains, the traditional retail piece should be a bonanza of easy, profitable sales, given how many people come into a Walgreens or a CVS to pick up their prescriptions. And excellent retail in turn should entice people to choose one store over another and visit often. That opportunity is even greater given the ubiquity of their stores: Some 78% of Americans live within 10 miles of a Walgreens. But consumers have choices, and Walmart, Amazon and Target have been more than happy to pick up that casual retail business, given their stronger e-commerce muscles and, Saunders says, much better prices.

“The drugstore is an ecosystem of a number of different parts of the business, from healthcare to prescriptions to retail and it only really works if you have all those engines whirring,” says Saunders. “Both CVS and Walgreens took their eyes off the ball ages ago and it’s had a detrimental impact on their pharmacy businesses.”

Both CVS and Walgreens have seen their front-of-store sales struggle for years, aside from a COVID bump fueled by vaccine-driven foot traffic in 2021. But retail is much more important to Walgreens than it is to CVS. (CVS has begun to see improvements in its retail business.)

While Pessina doggedly pursued Rite Aid, CVS was head down, continuing to build out its health care empire and buying health insurer Aetna in 2018 for a whopping $69 billion. (That same year, Cigna bought Express Scripts in another mega-deal, shelling out $67 billion.) CVS’s ownership of Caremark, the biggest PBM in the U.S., had spurred millions of member customers to get their scripts filled at CVS stores, a hold made even stronger with the Aetna deal. (Still, that deal is at the center of CVS’s own current travails: Aetna’s profitability has sagged because of rising health care costs.)

Walgreens did eventually pivot its M&A more toward healthcare, but to little success. In fact, those deals have weakened it further and were the key reasons behind its stock’s implosion.

In 2013, in a move that ultimately hurt its reputation, Walgreens made a big investment in the health technology company Theranos, hoping to open dozens of its blood-testing clinics within its drugstores; but Theranos fell apart in scandal as its main product failed amid a fraud scandal. In 2020, Walgreens invested in VillageMD; the next year, it grabbed a controlling stake for $5.2 billion. It is now trying to offload that network of primary medical care clinics.

Also in 2022, under then-CEO Rosalind Brewer, previously of Walmart and Starbucks, VillageMD paid $9 billion for CityMD, another clinic chain, in another deal that has not paid off. Brewer abruptly left Walgreens in 2023, and Walgreens has unwound or is unwinding much of the M&A it has conducted in recent years.

Wentworth, who had earlier been CEO of Express Scripts and had a long career as a pharmacy and healthcare executive, replaced Brewer. Though he didn’t have much pure retail experience, he has made clear the caliber of Walgreen’s drugstores had to be taken up a notch for the company to emerge from its slump.

“The stores are central to our strategy,” he told a healthcare conference in March 2024.

Squeezing out savings

Wentworth has so far concentrated on cost cutting, with an initial goal of hitting $1 billion in savings, and focused Walgreens on being better at its core pharmacy business. One early move was to announce those 1,200 store closings over three years (some 500 of them are slated to happen this year), on top of the hundreds it has closed in recent years, the better to focus on the 80% of its stores that do turn a profit.

Neither Walgreens nor Sycamore has said whether Wentworth will stay on once the take-private deal is done. But it’s telling that Wentworth was chosen as CEO despite his inexperience with retail. That suggested that Pessina, who will keep a 17% stake in Walgreens after the Sycamore acquisition, and the rest of the board valued Wentworth’s PBM chops as a former PBM CEO himself, above all else.

And indeed, those shrinking pharmacy reimbursements have been a major source of Walgreens’ malaise. Leerink’s Cherney has said that is Walgreens’ biggest problem to solve.

CVS, tapping its Caremark clout, recently found a promising solution to shrinking pharmacy margins. Starting this year, all commercial prescriptions filled at a CVS will be reimbursed at the cost of the drug plus a predetermined markup and a handling fee. This model is called “CostVantage,” and Cherney says Walgreens could easily have its own version. “It wouldn’t be at all surprising if Walgreens became a fast follower,” he said. After all, Wentworth knows the PBM world intimately.

As for Wentworth’s lack of a retail background, this is where Sycamore’s extensive expertise in that industry could be useful. Sycamore has a long history of buying distressed retailers and helping them optimize their store operations. It has done so for such retailers as Belk department stores, The Limited, Staples, and Talbots.

Walgreens has already taken some encouraging steps on the retail side. It has begun to beef up its roster of store brands with 300 new products; it is also remodeling many drugstores and is offering faster delivery than before. On the pharmacy side, Walgreens is trying to squeeze out costs with initiatives like using automated robotic prescription filling; it hopes to have that service in place by year-end in more than 5,000 of its stores.

On the other hand, Sycamore has never done a deal involving healthcare, raising some concerns about its ability to improve Walgreens’ underlying business. Media reports have suggested that Sycamore may break Walgreens into three pieces—its international business, its healthcare and its retail— essentially undoing almost all its M&A since the Boots deal.

Sycamore, and by extension Walgreens, will be taking on an enormous amount of debt—$12 billion—to make this acquisition happen. (Bloomberg estimates Walgreens could be facing an additional, separate liability of $1.5 billion from the opioid litigation against it; the chain has been accused by a number of state governments and the Justice Department of making millions of illegal opioid prescriptions, accusations it has denied.) Given Rite Aid’s recent bankruptcy, its second in consecutive years, because of the combination of deteriorating business and high debt, it’s not surprising to hear some alarms about the deal’s financing.

But bankruptcy theories aside, the even higher debt load and service post transaction certainly mean that Walgreens will have an even smaller margin of error in the near future. “They haven’t really cared for the business internally, and that’s led to the crunch they are in now,” says Saunders. It took a little over 10 years for the company to tumble from its Boots-merger heights to its current lows; its leadership probably doesn’t have 10 more years to right the ship.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com