Trump’s ‘art of the retreat’ may signal he’s setting Powell up to take the fall for economic turmoil

Trump’s tactical retreat on key points like Fed Chair Powell and trade negotiations with China signals a change within the White House—potentially lining up a scapegoat if its policies fall flat.

- Confidence in Trump’s tariff strategy may be waning after no major trade deals have materialized, prompting speculation that the administration is shifting from a strategy of bold negotiation to tactical retreat. Analysts suggest Trump’s recent softening toward Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell after months of criticism may be less about calming the markets and more about managing blame for potential economic fallout down the line.

A few weeks ago, the White House said media and analysts had missed “the art of the deal” when it came to Trump’s tariff policy. Now that no such deals have emerged, Wall Street is speculating that President Trump is more focused on “the art of the retreat.”

This tactic is evidenced on two counts, wrote UBS chief economist Paul Donovan in a note seen by Fortune.

“U.S. President Trump demonstrated the art of the retreat. [Trump] stated [he] had ‘no intention’ of firing Federal Reserve Chair Powell,” Donovan wrote. “Trump also said they would be ‘very nice’ in any trade negotiations with China, raising hopes that the tax burden on U.S. consumers may lessen.”

But the about-face on the Fed chairman—whom Trump had been lambasting for months—has raised suspicion among some analysts that the move may not merely be about calming markets, but about ensuring the Oval Office has a fall guy.

“On Powell, we’ve never thought that he’d be ‘fired,’” wrote Macquarie strategists Thierry Wizman and Gareth Berry in a note seen by Fortune. “Not only would the legality of a dismissal be challenged in the courts, but, even earlier, pressure from markets and even rating agencies would likely serve to halt the political process of a ‘firing’ in its tracks.”

Trump may have changed his tune because he realized the threats were legally empty, but the Macquarie duo had a different take: “The best reason for thinking that Trump would not fire Powell is that Trump needs Powell as a ‘foil’—someone to blame for any economic slowdown that may ensue. Indeed, if the Fed cut its policy interest rates aggressively, Trump would have little excuse for a recession apart from his own policy agenda.”

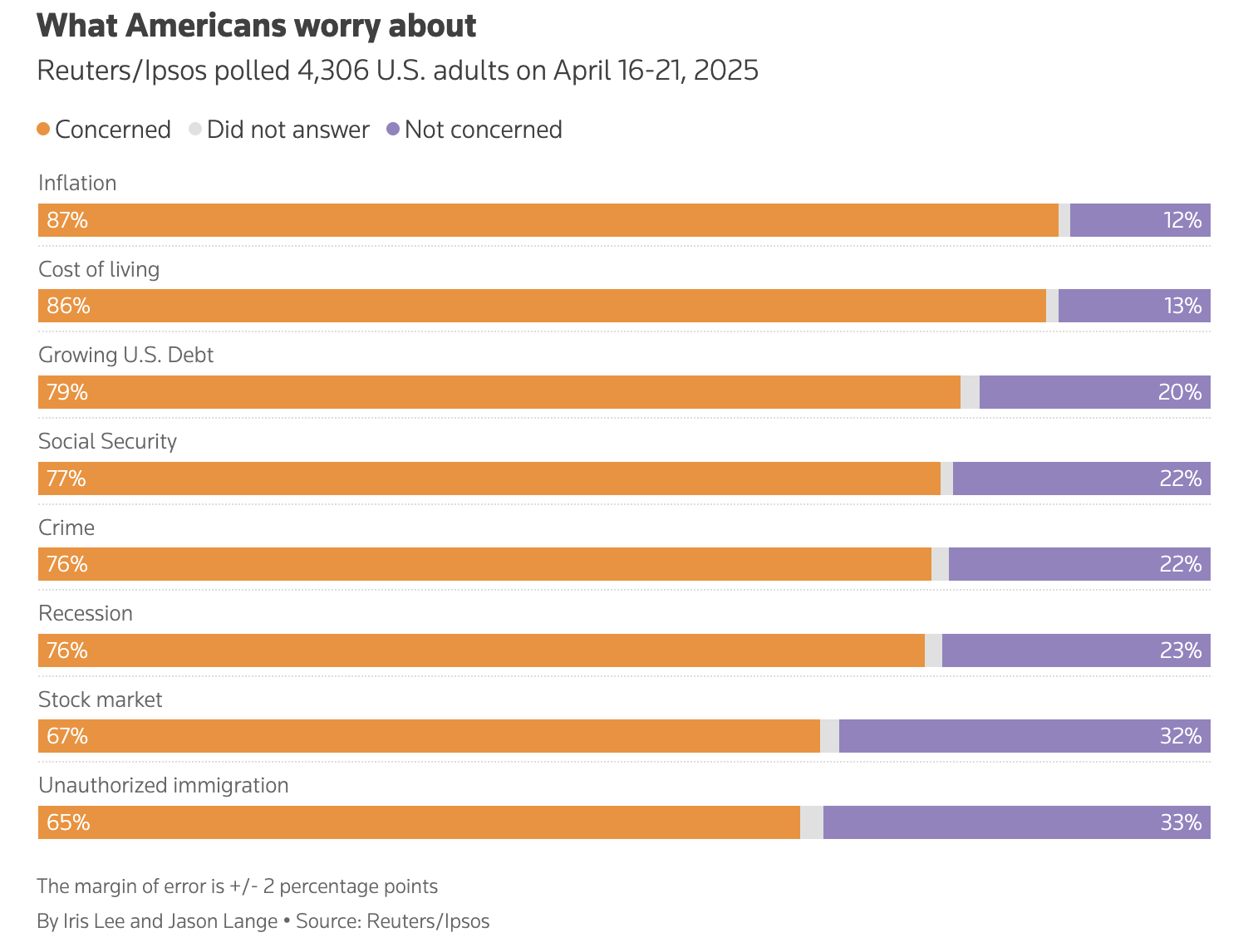

In a potentially inflationary environment courtesy of the Oval Office’s tariff plan, a dramatic rate cut is looking increasingly unlikely; Deutsche Bank notes that analysts priced in a 78% chance of a rate cut in June on Monday, but by Wednesday this had fallen to 57%.

And Trump’s attacks on Powell thus far could already provide the bedrock of blame that the White House may need to deploy in the event of an economic slowdown.

The president has already given Powell a nickname, “Mr Too Late,” saying that Powell is a “major loser” for not slashing the base rate in order to foster economic growth.

A ‘significant miscalculation’?

The fact that Trump is changing his tune on some of his loudest talking points indicates to the Macquarie strategists that the aggressive foreign policy out of the White House isn’t landing quite the way the Oval Office hoped.

For all the noise about the droves of countries lined up to cut a deal with Trump, such a contract has yet to materialize. Indeed, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has begun touting the benefits of being the “first mover” to encourage at least one foreign government to reach a deal.

Nations that had been earmarked for a quick agreement, such as Japan, have indicated they’re in no hurry. Further caution is now likely after China warned that any nation coming down on the opposite side of its agenda would face consequences.

This is not the “90 deals in 90 days” dynamic, fast-paced period of negotiations that the White House had promised.

And Trump may be tightening the thumbscrews to get the ball rolling, telling reporters in the Oval Office yesterday: “In the end, I think what’s going to happen is, we’re going to have great deals, and by the way, if we don’t have a deal with a company or a country, we’re going to set the tariff.

“I’d say over the next couple of weeks. Over the next two, three weeks. We’ll be setting the number.”

“Bessent’s comments on China ... point to the admission of a significant miscalculation on the part of the administration,” Wizman and Berry wrote.

“If this means that Trump is sidelining the administration’s ideologues, such as Peter Navarro, and giving more voice to pragmatists such as Scott Bessent, there may still be disengagement from China, but more slowly.

“The prospect of reengagement with the U.S.’s allies (the EU, Japan, India, Canada, and Mexico, etc.) also beckons. After all, if the administration can play nice with China, it can play nice with anyone.”

Markets will be buoyed by the notion that a lower tariff rate with China might indicate “a more predictable direction [of foreign policy] from here,” chimed in Jim Reid, global head of macro research at Deutsche Bank.

“In fact, we’re moving back closer towards Trump’s campaign pledges of a 10% universal baseline tariff and a 60% tariff on China, albeit two weeks into a 90-day reprieve on the more aggressive reciprocal tariffs,” Reid added.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com