Rabbithole: What Do People Get Wrong About Money?

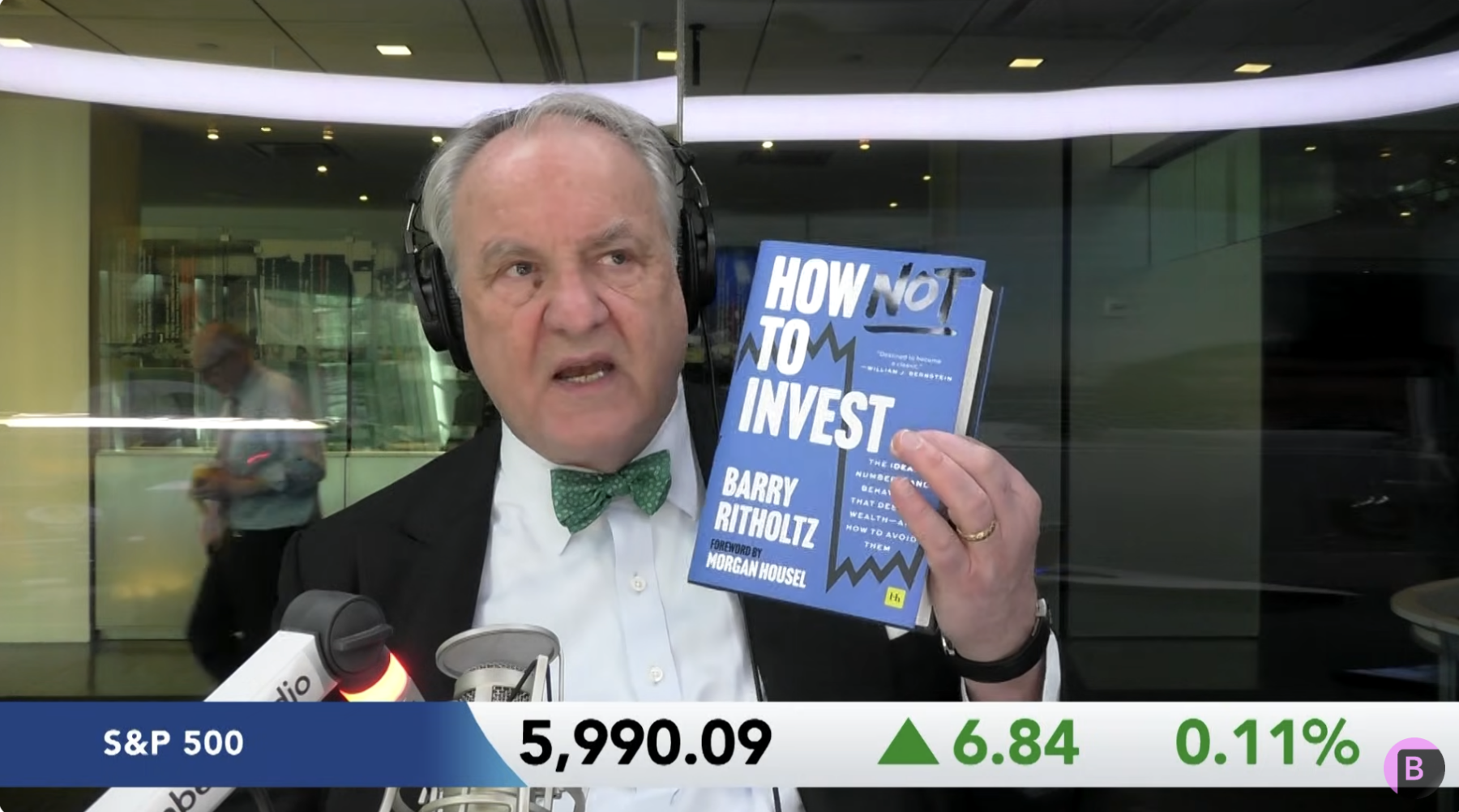

Money Delusions: What Do People Get Wrong About Money? David Nadig, “Rabbithole” March 7, 2025 I had fun chatting with Dave Nadig about philosophy, behavior, and investing (video after the jump). His new podcast is called “Rabbithole” because Dave does not do broad and shallow; rather, he picks a narrow topic and… Read More The post Rabbithole: What Do People Get Wrong About Money? appeared first on The Big Picture.

Money Delusions: What Do People Get Wrong About Money?

David Nadig, “Rabbithole”

March 7, 2025

I had fun chatting with Dave Nadig about philosophy, behavior, and investing (video after the jump). His new podcast is called “Rabbithole” because Dave does not do broad and shallow; rather, he picks a narrow topic and goes deep down the rabbithole for 30 minutes — which is only a few questions. Here is the full-length Q&A discussion. Enjoy.

Question: “Barry, your book How Not to Invest dissects numerous financial misconceptions. But let’s set aside markets and investing strategies entirely. What’s the most fundamental thing people get wrong about money itself—about the actual dollars we earn and hold?”

Answer: It is that Money is a tool – it is a means to an end; it’s NOT an end goal itself. And since I mentioned NOT, let me give you three more things Money is NOT:

-It is NOT a store of value (it’s a medium of exchange);

-It’s NOT the path to happiness, at least not how most people imagine;

-It frees you up from NOT doing things or spending time on what you don’t want to do; it allows you to focus your time and energy on what you want to…

Question: “You mention ‘denominator blindness’ in your book. How does this same blindness affect our understanding of what a dollar actually represents in our daily lives?”

Answer: The core of Danny Kahneman’s “Thinking Fast & Slow” is the differences between your fast, instinctual reactions and your more thoughtful, deliberate mind. His brilliant insights colored lots of themes in my book, and Denominator Blindness is a perfect example. Unless you have CONTEXT, FRAMING and NUANCE, you lose sight of what things truly mean…

Q: “In your section ‘Dollars Are For Spending and Investing, Not Saving,’ you challenge conventional wisdom. Can you elaborate on how people misunderstand the very purpose of currency?”

A: Money is NOT a store of value – to be useful, a dollar must maintain its value long enough for me to pay my rent or mortgage, buy food and energy, fund my entertainment and travel, pay my taxes, and get invested. It does that splendidly.

Q: “Your book discusses emotional decision-making extensively. What emotional relationship do people form with physical money that creates problems, separate from investment choices?”

A: It depends on your specific history with Money, be it traumatic or complacent. In my own family, myself and my two siblings each had a very different relationship with money. I grew up lower income. My sister grew up a little more comfortable, middle income and the youngest, my brother, was solidly upper-middle class.

I hate budgeting — its a waste of emoptional bandwidth — so I figured out I needed to make enough money so I never had to balance my checkbook; my sister grew up with more family income, when we were in the “keeping up with Jones” phase, and my brother, who is the most concerned with running up the numbers, not using money as a tool, grew up the most financially secure. Our experiences mashed up with three different personalities and three different outlooks on money.

Q: “You write about the ‘illusion of explanatory depth‘ – if I asked most people to explain what money actually is and how it functions, what fundamental gaps would you expect in their understanding?”

A: It’s true for most things – how are pencils made? How does a manual transmission work? Money is just another item we THINK we understand, but we really don’t.

Q: “The narrative that ‘the dollar has lost 96% of its purchasing power‘ appears in your book as a misleading claim. Why do these kinds of misunderstandings about money’s value over time persist?”

A: Two reasons: The starting point is a simple overlooked question: Why would you hold a pile of dollars for a century? If you had 10,000 dollars today and you wanted to give it to your great-great-grandkids in 100 years, would you keep it in cash? Just asking that question reveals how transparently deceptive this claim is. If you invest $10k today, in a century, it’s worth (brace yourself) ~$320 million. No one believes that, but when I walk people through an online returns calculator, their heads explode!

But the second part is the contextualizing side of the equation: You don’t spend 1925 dollars today; you spend 2025 dollars. So if you want to discuss purchasing power, the useful, thoughtful question is: How much has the average salary increased over that same period of time? It’s another version of “Denominator Blindness.”

Q: “How does our relationship with money change during different life phases? Do our misconceptions about what money represents evolve as we age?”

A: The standard answer is Accumulation, Maintenance Distribution, but let’s dig deeper. Who we are financially is very different than who we become in middle age or after retirement. We hopefully learn lessons about money, which we apply to ourselves, family members, friends, and if you write a book, your readers.

The strangest thing I came to realize was that the market crashes and bear markets that should have mattered the least to me were most terrifying. The ones that should have mattered the most I was blasé about. During the 2000 crash, I had no 401k, and my wife’s 403B was tiny. The GFC I had a more money at risk; Covid was fully invested, with a 401k, portfolio and of course, the firm.

As we grow and mature, you kind of learn that everything is cycle, you know how the movie ends. We learn the Solomonic wisdom of “This too shall pass.”

Q: “Throughout your career observing people’s financial behaviors, has there been a shift in how the average person understands what money is versus what it does?”

A: Around the edges, there is some improvement. It seems it’s still early days in the widespread understanding of how and why people behave the way they do around money and risk. It’s well understood academically, but it’s still seeping out into the real practice of wealth management.

Q: “If you could correct just one widespread misunderstanding about money itself – not investment strategy – what would make the biggest difference in people’s financial wellbeing?”

A: Optionality. Money gives you choices, freedom, and perhaps most important of all, agency. We radically underestimate how important that is.

Q: “Throughout history, money has been defined as everything from a ‘store of value’ to a ‘social agreement.’ In your observation, which philosophical concept of money do most people misunderstand today?”

A: Fiat currency is a collective delusion, albeit a powerful one. The country that produces the Dollar has a massive law enforcement mechanism and a standing army. That’s not nothing…

My favorite example if the collective delusion is the Rai stones on the island of Yap, part of Micronesia. Enormous round stones are their currency. They were too big and heavy to physically move during transactions, so the Yapese just transferred ownership rights. One fell off a boat and sank. Did not hurt the ownership – they could still use it as a medium of exchange!

Q: “From commodity money like gold to fiat currency to digital transactions – how has the evolution of money’s form changed or reinforced our fundamental misconceptions about what it is?”

A: All forms of money come with a narrative! A good narrative is an engaging story but not necessarily a truthful one. Therein lies the risk of believing something that is not true. The less connected to reality you are, the higher the probability of making an expensive mistake.

Q: “Aristotle distinguished between ‘natural wealth’ and ‘artificial wealth,’ with money falling into the latter category. Do you think people today confuse money itself with actual wealth in ways that lead to poor decisions?”

A: You’re making me reach back to college philosophy? OK, when Aristotle referred to “Natural wealth” he meant the resources that serve human needs and what was required for “Eudaimonia” or a good life: Food, drink, clothing, dwellings, ethics, philosophical debate – he was, after all, Socrate’s student – its akin to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

Artificial wealth is the pursuit of wealth as an end unto itself. I use the phrase “Purposeless Capital,” and it applies here. It’s beyond materialism, its excess. It was later adapted in the New Testament as “For the love of money is the root of all evil.” (The oft used misquote is “money is the root of all evil”). That should give you an idea how influential Aristotle was.

Q: “The economist Georg Simmel wrote about money as an ‘absolute means’ that becomes an ‘absolute end.’ How do you see this transformation playing out in how people relate to the dollars they possess?”

A: This goes back to what I said earlier, that money is a medium of exchange. It should facilitate trade. It should not be the end goal.

Q: “John Maynard Keynes talked about ‘money illusion’ – our tendency to think in nominal rather than real terms. How does this cognitive bias shape our relationship with cash today?”

A: We tend to think in nominal rather than Inflation-adjusted terms. I have noticed this personally in major purchases like homes or autos. Our perceptions lag; our frame of reference is the past few years. We get anchored to our prior experiences. Kind of reminds me of the Paul Graham quote: “When experts are wrong, it’s because they’re experts on an earlier version of the world.” Even non-experts think and behave that way…

Q: “Some philosophers view money as a ‘claim on human labor.’ Do you think most people understand what their dollars actually represent in terms of social relationships and obligations?”

A: Back to the medium of exchange discussion: First and foremost, you exchange your time & expertise for money. Secondly, you “work” (that aforementioned exchange) and hopefully derive a feeling of satisfaction that what you are doing is worthwhile and good. Where you go beyond that is up to you…

Q: “Marx critiqued money as having a ‘fetish character’ where we attribute powers to it beyond its functional purpose. Where do you see this playing out most dramatically in modern attitudes toward money?”

A: Obviously, the idea that money buys happiness. My experience has shown that it buys the elimination of stress and woes that the lack of money creates. But it gets more complicated from there. Money buys some happiness up to $75-90k (depending on which research you look at), then tails off at ~$400k, but specific life experiences — like divorce — shatter the data results into very different outcomes.

Q: “From the Bitcoin whitepaper to MMT, competing theories of money have gained traction in recent years. Has this theoretical debate changed how average people conceptualize the dollars in their wallet?”

A: I honestly do not know the answer to that. I cannot tell you how people conceptualize the money in their wallets. I have 30,000 foot data on spending and contentment and lots of fun anecdotes, but I really don’t know…

Q: “Historically, money has been understood as both a ‘medium of exchange’ and a ‘unit of account.’ Which of these functions do you think people most fundamentally misunderstand?”

A: These are 2 sides of the same coin. Units of account seem inevitable once you go beyond barter and basic trade.

Q: “The anthropologist David Graeber argued that money emerged from debt rather than barter. How might this origin story change how we should think about the nature of the cash we hold?”

A: Full disclosure: I have his book “Debt: The First 5000 Years” on my shelf and I have been intimidated by how dense it is. His core argument makes intuitive sense – credit/debt predates money by 1000s of years, so his core thesis seems to eb well supported by history.

I keep coming back to the same takeaway: Money, including risk capital, credit, leverage, etc. are simply tools. Used properly, they can work wonders. Misuse them, and well, if this was Twitter, I’d say “fuck around and find out…”

~~~

Thanks Dave, for the very deep and thoughtful questions…

Coming March 18, 2025

see more at HowNOTtoInvestbook.com

The post Rabbithole: What Do People Get Wrong About Money? appeared first on The Big Picture.