Crushing the dollar won't solve America's debt problem. It'll make it worse

Trump wants a weaker dollar. He shouldn't.

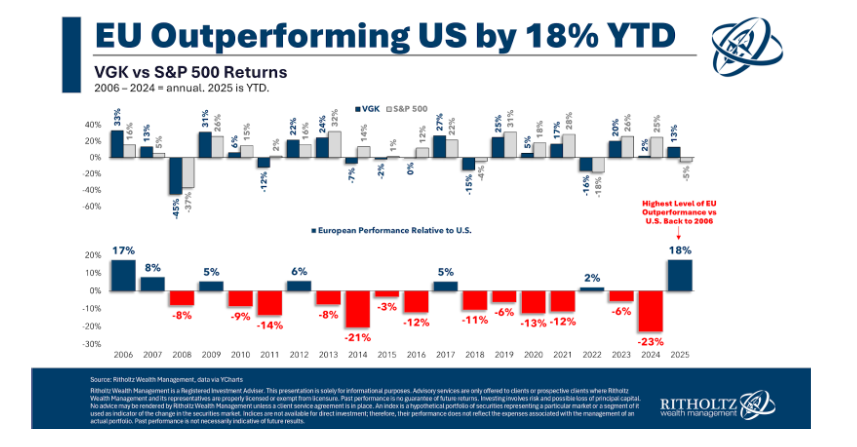

Stocks have been hugely sensitive to tariff-related headlines since President Donald Trump took office in late January, with the S&P 500 sliding into correction territory earlier this month amid a $5 trillion selloff.

The bigger, and potentially far more damaging, impact of the president's economic agenda, however, has yet to materialize and could challenge one of his key ambitions in coming months.

Trump appears to be following, loosely at least, strategies laid out in the Project 2025 series of essays and policy ambitions published prior to the 2024 election race.

A key economic-policy component of those goals centers on a complicated plan to weaken the U.S. dollar in an effort to induce a larger domestic manufacturing industry while stoking American exports and rewiring global trade relationships.

In simple terms, it would require the biggest U.S. trading partners, many of which hold trillions of dollars of U.S. government debt, to agree to sell those holdings, or swap them for longer-term bonds. In exchange they'd receive relief from tariffs plus favored access to the world's biggest economy.

Dubbed the Mar-a-Lago Accord, in reference to a similar agreement to weaken the greenback in 1985 known as the Plaza Accord, the multilateral pact would theoretically weaken the dollar, trim the weight of U.S. treasury securities held by foreign central banks, and narrow America's trade deficit.

But there are two problems.

It won't happen and it won't work.

That's $8.5 trillion with a 'T'

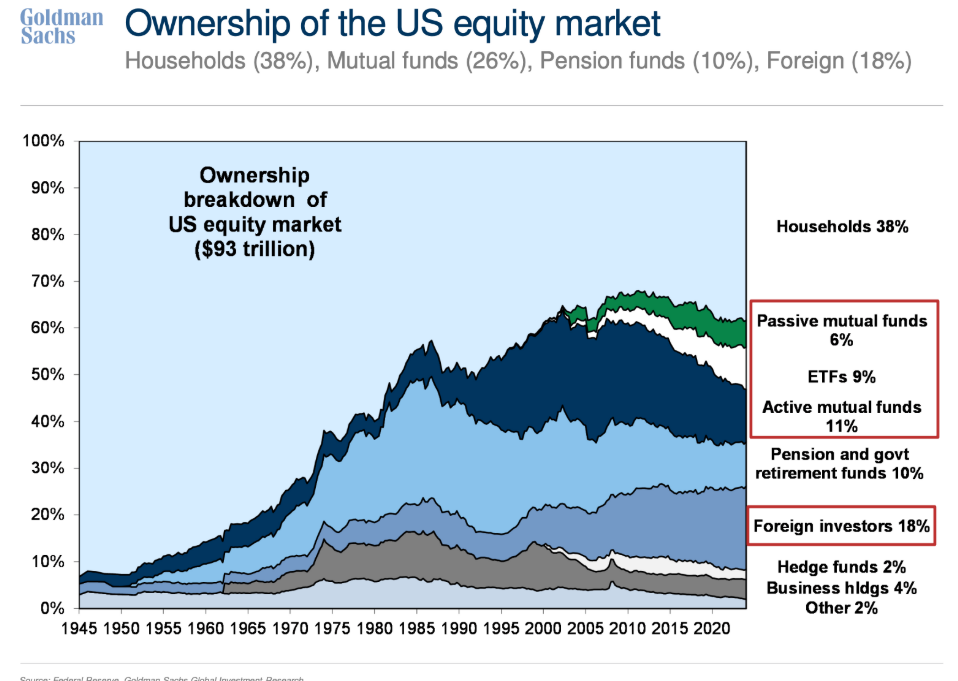

First and foremost, with foreign investors owning around 25% of the overall U.S. debt — a tally of around $8.5 trillion, which tops even that held by the Federal Reserve — inducing the sale of those assets is an incredibly risky process.

Aside from asking the very reasonable question of who would buy them, coordinated selling would trigger a drop in Treasury bond prices and a corresponding surge in yields, adding immense pressure to both government borrowing rates and consumer lending costs.

Secondly, asking any trading partner to dump their U.S. treasury securities and incur significant losses, while just recently having slapped tariffs on the goods they export into the U.S., seems like a tough sell.

Related: Legendary hedge fund manager sounds alarm on US debt (Here's why he's wrong)

It's even more difficult when the end result is to make those exports more expensive (a weaker dollar raises the value of other countries' currencies, making their exports less attractive to U.S. buyers).

Attracting signees to any Mar-a-Lago Accord that promises immediate losses, with the prospect of more to come, seems bleak at best.

On the domestic side, the accord's ambitions are just as damaging. To mitigate the spike in Treasury yields that would surely follow its enactment, the government would have to induce U.S. buyers to take up the slack.

That means billions, if not more, flowing out of equity funds and into Treasury portfolios, sending stock prices sharply lower.

Don't ask the Fed to buy in

The Fed could be persuaded to buy them as well. But that would almost certainly put the central bank's cherished independence into question, as it would indicate a willingness to support fiscal and political ambitions over its legally binding mandate of price stability and full employment.

In turn, that would undermine confidence in the Fed's inflation fight, and likely would deanchor market rates from the Fed's, triggering a dangerous surge in Treasury market and interest rate volatility.

The hit to consumers would be significant as well. They would see higher mortgage rates (which are tightly linked to 10-year Treasury bond yields), higher-priced domestic goods (since cheaper exports would be locked out) and softening purchasing power (tied to the weakening greenback).

Related: Tariff risks handcuff Trump and Fed's Powell

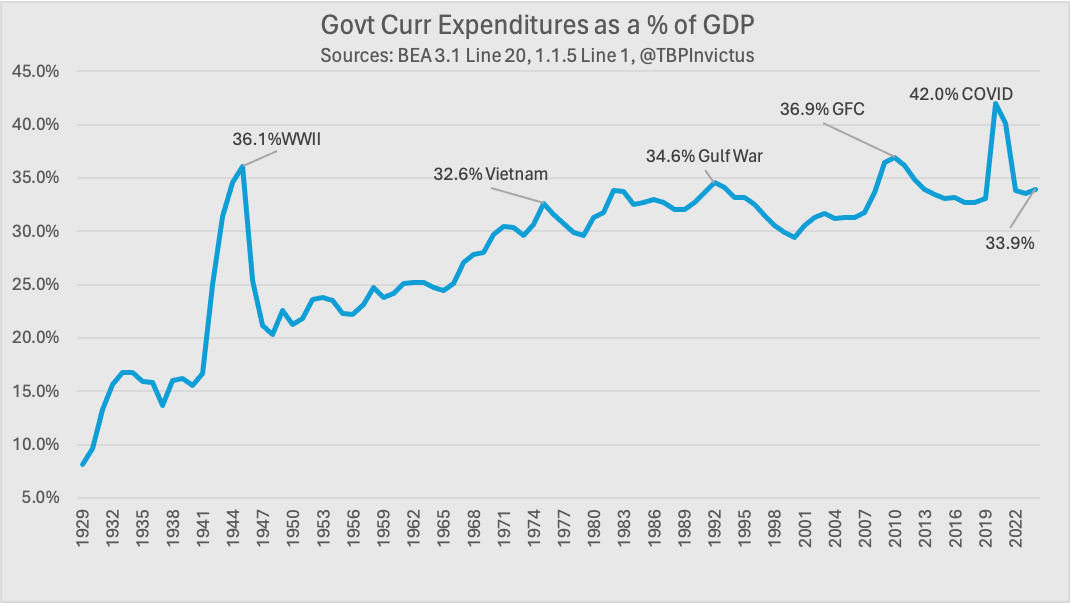

And it's not as if the U.S. is suddenly on course to trim its overall debt pile, which currently stands at $36 trillion and is swiftly on its way to $50 trillion over the next 10 years.

Trump's planned tax cuts, which are likely to cost $4.5 trillion, are being offset by only around half that total in spending cuts, even when factoring in a generous result from Elon Musk's effort at overhauling the federal workforce through the Department of Government Efficiency.

Seeking to make your debt more expensive by weakening the dollar, while simultaneously discouraging foreign investors from buying it, doesn't seem like a winning strategy.

Trump dollar policy is 'playing with fire'

And even if it were to result in the onshoring of some American manufacturing, it wouldn't likely offset the ways in which the U.S., and indeed the global economy, is likely to change over the coming years as a result of developments in AI, automation and robotics.

"The idea of encouraging foreigners to leave the U.S. Treasury market at a time of 6%+ budget deficits seems like playing with fire," said ING strategists lead by Chris Turner in recent analysis of the accord's proposals.

More Economic Analysis:

- Gold's price hit a speed bump; where does it go from here?

- 7 takeaways from Fed Chairman Jerome Powell's remarks

- Retail sales add new complication to Fed rate cut forecasts

"And equally the idea of dangling currency accords/threats to weaken the dollar may prove counterproductive if a stronger dollar is what's required in the shorter term to insulate U.S. consumers from import tariffs," they added.

More expensive debt, more expensive goods, and the end of U.S. dollar exceptionalism. That not likely to make America great again.

Related: Veteran fund manager unveils eye-popping S&P 500 forecast