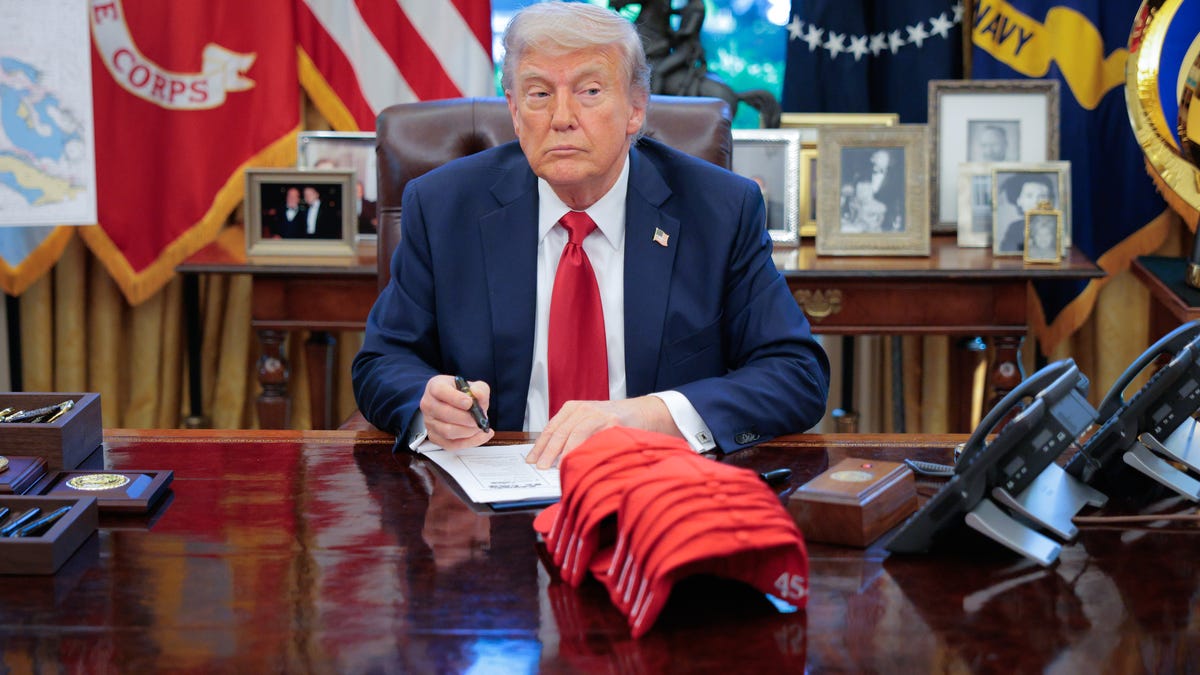

At the Money: Austan Goolsbee, Chicago Fed President on Tariffs, Inflation and Monetary Policy

At the Money: Chicago Fed President Austan Goolsbee on Tariffs, Supply Chains and Inflation (March 5, 2025) What is the potential inflation impact of tariffs? Can the Fed ignore supply-chain disruptions that drive up prices? How should investors view the relationship between trade policy and inflation in the current economic environment? This… Read More The post At the Money: Austan Goolsbee, Chicago Fed President on Tariffs, Inflation and Monetary Policy appeared first on The Big Picture.

At the Money: Chicago Fed President Austan Goolsbee on Tariffs, Supply Chains and Inflation (March 5, 2025)

What is the potential inflation impact of tariffs? Can the Fed ignore supply-chain disruptions that drive up prices? How should investors view the relationship between trade policy and inflation in the current economic environment?

This week, we speak with Austan Goolsbee, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. Previously, he was Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, Chief economist for the President’s Economic Recovery Advisory Board, and a member of President Barack Obama’s cabinet.

Full transcript below.

~~~

About this week’s guest:

Austan Goolsbee, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago

For more info, see:

BIO: Chicago Federal Reserve Bank President

Chicacgo Booth School of Business, Robert P. Gwinn Professor of Economics

Masters in Business (coming soon)

~~~

Find all of the previous At the Money episodes here, and in the MiB feed on Apple Podcasts, YouTube, Spotify, and Bloomberg. And find the entire musical playlist of all the songs I have used on At the Money on Spotify

TRANSCRIPT:

Inflation tariffs, egg prices, commodities, geopolitics, inflation, is very much on investors’ minds. I’m Barry Ritholtz and we’re gonna discuss how investors should think about. Inflation as a driver of returns. To help us unpack all of this and what it means for your portfolio, let’s bring in Austin Goolsbee.

He’s president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. Previously he was chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors and member of Barack Obama’s. Presidential Economic Recovery Advisory Board following the great financial crisis. So let’s just start out with a simple question. You’ve talked about the golden path between inflation and recession.

What lesson should the Federal Reserve take from our recent and rather successful bout with, uh, disinflation? Yeah, Barry, thanks for having me on. Look, I called the Golden Path. You’ll remember as I came into the Fed, I started the very beginning of, of 2023 in December of 2022. It was the Bloomberg economist who said there was a 100% chance of recession in 2023 because.

The historical record suggested that to get rid of inflation, you had to have a big, nasty recession. That’s what had happened at all times, and what I called the golden path was in 23, we had as almost as large a drop. In inflation that we have ever had in a single year. And not only was there not a recession, the unemployment rate never even got above 4%.

A level that a lot of folks thought is below full employment. Um, that, so that was a Golden Path year. And I think one of the principle lessons, there were a couple of principle lessons that explain how it was possible. One was. The supply side was healing on the supply chain, and there was a big surge of labor force participation from a number of groups.

I think a, a lot of it tied to the workforce flexibility, but if you saw, if you looked at self-described disabled workers, highest labor force participation ever, if you looked at, uh, child age. Women, again, highest labor force participation ever. So you got a number of positive supply shocks that are exactly what allowed for the immaculate disinflation, which the people who thought that was impossible use that phrase mockingly.

But that is exactly what happened. And now, fast forward to today. Um, so in a way transitory became, as Steve Leeman’s phrase, transitory, but it, it was all because the supply side, when you get negative supply shocks, they do heal. But one of the lessons of COVI was, that might take longer than you thought ahead of time because the supply chain.

Is complicated, the modern supply chain, and you, you know, that the, the Chicago Fed is the seventh district and we’re like the Saudi Arabia of, of auto production. Uh, in the seventh district. We got Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, soon. If you go talk to the auto suppliers, that’s sounds like the mother of all supply chains.

Okay? So a single car has up to 30,000 different parts and components in it, and every single one of ’em has its own supply chain. And you’ve probably seen some of these people that will track one individual part. Through the US supply chain and the way that it cut, you know, a transistor came from Asia, then they sent it to Mexico, they put it into a capacitor.

They put the capacitor in a seat, gets sent to the seat manufacturer in Michigan, it goes to Canada, comes back to the us, finally gets put in a car and you go buy it on the lot and drive it out. In an environment like that, the spillovers take can take a long time. That’s what we saw in Covid that. You couldn’t get computer chips, so you couldn’t make the electronic seat so they couldn’t make the car.

So the price of cars went up. Then that meant the rental car companies couldn’t get new cars, so the price of rental cars went up. Then the, the whatever, the used cars salesman who used the rental car, and so that thing played out over years, not weeks. My fear now is that if you’re going to do something negative on the supply side, and make no doubt about it, tariffs on intermediate goods like steel, like parts and components, like the things that are getting sent from auto factories, from suppliers in Canada that are getting sent over the border to be fa fabricated in into the car in Michigan.

That’s a negative supply shock. And I hope that it’s small enough or short-lived enough that it doesn’t reteach us the lessons of covid. But, but it might, the, the, the lesson of Covid was that can have, if it’s big enough, that can have a longer lasting impact than, than you might have thought at the beginning.

So let me ask you a question, um, about. That recession that never showed up, forget a hundred percent chance of recession. 22, 23, 24. Half of the Wall Street economists were forecasting recessions and no less August. And, and well regarded economists, uh, than Lawrence Summers was saying, Hey, you’ll need 10% unemployment to bring this inflation down.

What was it about? The historical models that seem to have gotten gotten, that seems to have gotten this economic cycle so wrong? Well, that, that’s the critical question. And summers said it either had to go to 10%, or if it went to 6%, it would take five years of unemployment above 6%. I think the thing that it got wrong, I

That worldview got wrong is that it was rooted in almost all previous business cycles were regular demand-driven business cycles. And that’s, that’s the logic in a demand-driven business cycle. You overstimulate, e inflation goes up, inflation expectations go up, and you have a hell of a time getting it out of there.

As, as you know, I was a old dear friend. With Paul Volcker, and he was a mentor of mine and, and a, and a personal hero, really. Um, and one of the lessons of the Volcker episode, which was a time when inflation expectations went way up, is that it’s extremely painful if the Fed or the central bank does not have credibility.

It’s extremely painful to get rid of inflation. In an environment where the Fed is credible, so that even as headline CPI, inflation was approaching double digits, the Fed was announcing we will get inflation back to 2%. And if you go look at the market estimation from tips or from others, people believed it.

If you looked at the, what do you think inflation will be in five years, they were saying it will be back to 2%. That is a sign of credibility of the central bank. So A, you must have credibility, and B, you must have the good fortune. That’s positive supply shocks in our case, one, a big increase in labor force, uh, participation.

That that was enabled, I think, by some of the more flexible work arrangements. Two, that we had had such a horrible supply chain experience coming through covid with shortages, et cetera, that could heal. And then three, a pretty substantial uptick in the rate of productivity growth. That combination was a lovely combination that allowed inflation to come down without a recession.

And I think that the, the chat GPT AI version of a central bank. Would’ve got it wrong because it would’ve been based on a training sample that was a whole bunch of demand shocks. And this really wasn’t a demand shock induced, uh, business cycle. And you don’t look, it doesn’t take somebody with the market acumen that you have Mary, and it certainly doesn’t take a PhD to look out and recognize that the covid business cycle was driven by.

Industries that are not normally cyclical. Normally cyclicals like consumer durables. Or business investment are the thing that drives the recession. And here the demand for consumer durables went up because people could not spend money on services. This is the only recession we ever had that came from people not being able to go to the dentist.

And the thing about that is like the, the, the dentist is normally recession proof. And so that’s why we, everybody should have been more humble in pronouncing. What the future would be coming out of such a weirdo business cycle. Um, and, and we’re still kinda living with that, so, so let’s talk about humility.

You have specifically mentioned that the Fed needs to be, quote, more careful and more prudent about rate cuts due to the risk of inflation kicking back up again. So what specific inflation indicators are you watching closely in 2025? Okay. I’ve, I’m, I’m thankful, Barry, I thought you were gonna be like, let’s talk about humility.

You once said, and I thought, you’re gonna be like, you’re not, you’re not a humble person. Look, my, I, I have actually been. B before we got to this dust in the air period where everybody’s talking about major, either geopolitical changes to conditions or changes to policy conditions that might affect inflation.

I’ve been more confident. I, I, I’ve had comfort. We’re still on the path to get inflation to 2% and we could cut rates now. I’m open to, to being proven wrong, and if I adjust the, the, uh, I’m in the data dog caucus, if, if the data come in and the, the outlook is changing, for sure, I would change my view. But the, I, I think it’s critical to answer your question specifically of, well, what should we look at in inflation?

I think number one. You want to look at the through line on inflation, not get overly indexed on monthly gyrations. It’s a very noisy series. Mm-hmm. Okay. So looking over a longer period and what matters is the new months coming in the the inflation that’s a 12 month backward looking average, which is usually what we’re reporting it, 11 of the 12 months.

That are included in that are not new information. We already knew that. We knew, for example, that the blip up in inflation last January, more than a year ago was gonna fall out the back, and so that it would be very likely that the 12 month average would start dropping here in the first quarter, but that would not be a sign that the inflation is falling right now.

The inflation already fell. This is just like how, how we do the average. So number one, I put a lot of weight on the new months coming in and trying to get the through line of that, not just react to, to one month. And. Uh, second thing that that helps me that I, that I find helpful is looking at the components of core inflation.

Now, I know it can drive people nuts, like it drive my mom nuts that we put our focus on core inflation and not food and energy inflation because my mom’s like, what do you mean you’re not paying attention to food and energy inflation? That’s very public, uh, top of mind for her. It is because those are so variable.

They’re up, they’re down. The, we think the better observation is to look at core, and then within core there’s goods, there’s services, there’s housing. Our problem has been. Goods inflation had returned to deflation and was looking good. Housing inflation’s been the biggest puzzle. Mm-hmm. And services inflation.

Pretty persistent. The thing that have given me, the things that have given me a little more confidence lately is that even as we had a bit of a blip up in the inflation. Here, the components still look pretty good. The housing inflation has finally started falling on a pretty persistent basis as we’ve been wanting it to services getting closer, much closer to what it was pre covid housing back close to what it was pre covid.

And the thing that has been firmed up here in the last couple of months has actually been goods. And the thing about goods inflation is. As you know, uh, and, and as some of my, uh, research showed before I ever got to the fed goods, inflation over long periods is actually deflation. The, the, the, the 2% inflation that we were at before Covid was housing three and a half to four.

Per year services two and a half per year and goods minus a half to minus one per year. And so I think it’s overwhelmingly likely that goods will go back to that very longstanding trend and as it does, so that’s the, those are the kinds of things that give me confidence. So you mentioned housing. We seem to have two ongoing issues with housing.

The first is it appears that since the financial crisis. We’ve significantly underbuilt single family homes as underbuilt. Yeah, I agree with that. As the population can and, and multifamily. So, so you have the population growing, you still have fairly, uh, decent immigration numbers. Too much demand, not enough supply.

The first question, what can we do to generate more supply and housing, do higher rates? Operate as a headwind against builders, contractors, developers, putting up more housing. Look, this, this is a t tangled, uh, this is a tangled web, uh, that is critically important to, to the economy. You’ve seen the relative price of housing go way up post covid.

But the one thing that I wanna highlight is. Yes, it’s very noticeable, but it’s not new. If you look like, like I said, for the whole decade plus pre covid, you had house prices going up three and a half percent a year. Goods prices going down 1% a year. If you just compare housing relative price versus going to Costco, relative price.

A thing that compounds 5% a year for 15 or 20 years. Yeah, that’s gonna be a really big difference at the end of that time. And so I think one component that people are seeing, and they’re not wrong, you see the frustration of young people. They say, you know, when my, when my dad was, was 25 years old, he on one job could, could afford a decent house and I can’t buy a condo.

They’re not wrong. The relative price of housing has gone way up. I think some component of that is, uh, regulatory in nature and business permits, and I’ve been convinced by a, by a bunch of the evidence that land use regulation have made it very difficult for us to build housing of any form, single family home, multi-family homes.

I have a. I did some research that was about the construction industry. And the another thing going on is that overall productivity in the construction industry is not only been stagnant, it’s actually over long periods of time been negative. Mm-hmm. That we’ve, we’ve gotten worse at building the same things that, that we did 20, 30 years ago.

Um, so I think that’s, that’s part of it. And I think you’re highlighting that. Uh, rates do have a twin. They, they, they do have a twin, twin effect. One is they affect demand, but the other is they do affect construction. Um, and so I, I think in a higher rate environment, if you’re trying to cool the economy, this is always true.

But the shift of more and more of our mortgages to being 30 year fixed. Than they were say in 2007, um, have meant that changing rates can have more of a lock-in effect than. And, and, and it kind of dull the immediate impact of, of monetary policy than, than it does in, in a, in a more immediate mortgage impact environment.

Let, let’s wonk out a little bit about housing. Yeah. Um, yeah. Owners’ equivalent rent have been this bugaboo for a long time that some people following the financial crisis said had understated housing inflation. Now there’s some people, uh, saying something similar. How do we, and I know the Fed has looked at this, there’ve been a number of white papers that have come out of the Fed.

How should we think about the equivalent of renting versus ownership in terms of the impact on inflation? Uh, the, IM, uh, the, you raised several key critical points. Um, if we’re gonna walk out on housing and inflation. Point one, it’s not single family home sales prices. It’s owner equivalent rent. Plus rents.

And the reason it’s that is because part of buying a house is a financial asset. So if you’re buying a house and the value’s going up and you’re selling it for more, and if there’s speculation, that’s not really housing what you’re trying to get. That’s, that’s not really inflation. What you’re trying to get for housing inflation is something like the CPI, how much more does it cost for the same housing services?

Um, and that’s why they try to compute owner equivalent rent and, and, and similar 0.2, that’s, there’s a heavy lag in the way they do it. So in a way, the critics were correct that it was understating inflation. On the way up and the, the other critics are right that now it’s overstating inflation on the way down.

For the same reason that it’s kind of like if you were measuring average rent and people were raising the, it was a time when the market was raising the rent. It’s gonna take time before that shows up in average rents because. The, the contracts last for a year. Andre, 12, 20 months, they’re over. So you get this automatic lag in there.

I think that has been a major component of measured housing inflation because if you go look at market-based measures, like from Zillow or others, they were showing rapid drops in the inflation rate back to, or in some cases even below. What inflation was before Covid started and so that’s been the puzzle.

That’s is been our impatience. Why hasn’t it shown up yet? That’s been true for quite a while. And the lag theory, it’s should start showing up. Well, finally it has, and that’s why I have a little more confidence that the housing inflation improvement. Will be lasting is, it was, it took a long time to run up and now it’s finally started coming down.

So I think it’s, it’s probably got legs of coming down. Um, so I, I think those are two key components on, on the housing inflation side. We could get, we could even go into a third layer of wonky, but it’s more subtle, which is. The component if, if you think about rents and say market rents in Zillow or who are renters versus who are new home buyers, there’s sort of different markets.

And so it doesn’t have to be that the inflation rate of the Zillow market rents matches the owner equivalent rents. Th that they’re measuring at at the BLS because they might be different new renters and, and existing tenants might be a little bit two separate markets. Makes a lot of sense. You mentioned the 2% inflation target in the 2010s, an era dominated by monetary policy.

The Fed had a 2% inflation target. Now, in the 2020s, we have a primarily fiscally driven economy, or at least post pandemic. Yeah, that’s what it feels like. You’ve said you’ve turned 180 degrees on the inflation target questions since your initial thoughts in 2012. Tell us about that. Explain that. Okay, so in 2012 th there had been vague targets.

In 2012, I believe, is when the Fed officially said, where you have a 2.0% inflation target and you go back and look, I wasn’t at the Fed. I was critical. I was publicly critical on the grounds that that conveyed a way, false sense of precision to me. That, that if, if I asked you just take the, take the standard deviation of.

Of the inflation series and ask yourself, how many observations would you need to get to be able to distinguish between a 2.0% inflation rate and a 2.1% inflation rate? And the answer was like decades. You’d need decades of monthly observation before you could tell no, no, this is 2.1, not 2.0. So that was my critique.

Fast forward to. The inflation, now it goes way up. And the, the, the, the, the one wonky thing that you gotta know, which you already know Barry, but the, the average person might not know is I. The 2.0% inflation target is for personal consumption, expenditure inflation. PCE inflation. That’s not CPI. It’s a little different.

They have different weightings of, of what goes into it. We believe the PCE measure. Which instead of the CPI measures a basket. Mm-hmm. And the PCE measures everything consumers spend money on. So it’s the better measure. But just as a technical CPI of 2.3 is about the equivalent of a PCE of 2.0. Okay. We go through covid, the inflation post covid soar to almost double digits.

In long run inflation expectations measured in the market never go up. They remain exactly and they’re off of CPI. Importantly, they remain exactly 2.3%, and so I said either that’s the biggest coincidence in the history of price indices. Or else the inflation target of 2.0 is serving as exactly the anchor that its advocates said it would be.

And at that point, I changed 180 degrees and I, not only am I not opposed to the inflation target, I. I think it’s critical. It’s vital and it is serving as exactly the anchor that we needed, so So it’s a magnet, not necessarily magnet. A landing spot magnet. Exactly. Really interesting’s a you, you mentioned, but it will be the landing spot.

It will be you, you, we’ll get the 2%. You mentioned inflation expectations when, when we look at some of the survey DA data in 2020 and 21, right before inflation really exploded higher. They were really low. And then go fast forward to June, 2022, just as inflation was peaking, they were really high. How close attention does the Fed pay to inflation expectation?

It seems that it’s very much a lagging, not leading indicator. Uh, now fascinating. Uh, in a way a, I should have said at the beginning. Uh, you know the rules. I’m not allowed to speak for the FOMC Sure. Or the Fed only for myself. Yes. That gives them great relief. That gives my colleagues great relief. Um, in the world of food safety, the thing that characterizes almost every, uh, worker in the food supply chain is frustration.

Why do we have to wash our hands all the time? There’s no, nobody’s ever getting sick from the food. And it’s only because they’re washing their hands all the time that nobody’s getting sick from the food. I feel that way. A little bit about inflation expectations. They are lagging indicators. If the Fed has credibility and is doing it right, as soon as that’s not true, they become very instructive, forward-looking indicators.

The, the only thing that I want to emphasize as well is. N Now we’ve actually started to get a couple of observations where not short run expectations, but longer run expectations actually bumped up in the University of Michigan survey, and since I had said this about how important inflation expectations were as a measure, a couple of folks asked me, well, does that make you nervous?

And yes, but. A, I’ve always said I value the market-based measures more than survey-based measures, and one month is no months. But make no doubt about it, if what we started to see was persistent, a persistent increase in long run expectations of inflation in surveys and markets. And for example, if you started to see long rates rising, one for one with long run inflation expectations, then that fundamentally to me means the Fed’s job is not done and we’ve got to go address that.

Because if you, that’s the, that’s one of the main lessons of the Volker experience. And central banks around the world, if the expectations start rising, it is really hard to slay. You don’t have to just slay the inflation dragon. You have to go convince people that it’s going to stick, and it kind of the only way we know.

The only way we know central banks have been able to convey that is to have awful recessions where they grind down wages. Mm-hmm. To convince people look that we will keep the job market, um, as suppressed as we need to. As proof that we’re serious. So we don’t ever want to get back into that situation if we can help it.

Last question on inflation. You have mentioned that prioritizing real economic channels, the real economy over wealth effects. Can you, can you explain this perspective? Why does the real economy channels matter more to the wealth effects? I, I always thought the wealth effect was. So dramatically overstated because you know, it’s typically the wealthy that owns most of the stocks, and the real economy is the real economy.

But I’m curious as to your perspective. Yeah, look, it, it the, I would expand it a little more than just the wealth effect. My view is the Federal Reserve Act tells us we should be looking at the real economy, maximizing employment and stabilizing prices. The stock market. Other financial markets can influence those two things, partly through the wealth effect.

But I’ve, by the very first speech I gave, when I got to the, to the Fed, I went out to Indiana and the, uh, factory, um, where they make the, where they make RVs and. And, uh, a, a community college where they train people for advanced manufacturing. And I said this, look, the fed by law is supposed to be looking at the real economy and financial markets.

To the extent they’re affecting the real economy, we should pay attention to them. But that’s, that’s it. Like, let’s remember the priorities. Um, I quantitatively agree with you. I think there are a number of people who overweight. The, the wealth effect and its impact on consumer spending. Uh, and I don’t want us to get into a mindset that the Fed has an accomplishment.

If it does something and it changes the financial markets, that’s a, that’s a indirect, I in my, in my worldview, if you get the real economy right, the financial markets will benefit, but. Doing something to try to create higher equity prices or benefit the financial market. That should not be the Fed’s goal.

The Fed’s goal should be stabilize prices, maximize employment, and and focus on the real side. And if you do both of those, stock market tends to do well under those circumstances. The stock market does great, takes care of itself. And that’s how it should be. That’s how it should be. Well, thank you Austin.

This has been absolutely fascinating. I have a, so we’ve only done the first segment, but it’s 1145. How hard is your 1145 stop. 10 45 by you. What can we do? How do you think we could do the next in five minutes? No, I, I got a board. I got my, my Detroit board of directors that starts at noon in a different room.

So I could go, I could go. Five, six minutes. But then I got, so let me just give you, I’ll just give you one more question on inflation and if we ever wanna redo the second discussion on monetary policy, we can always squeeze that in. But I need like, so neither you nor I are brief, so we tend, we. Tend to go a little long and they’ll tighten this up for, for broadcast.

Okay. Do you want me to be tight? I can be tighter. That’s fine. Um, but to go through 10 questions can, let’s take five minutes. We got five minutes. However much we want to fit in there. All right. So let me find my best question from this. Um. You wanna know one from here and one from the other, or I’m just, yeah, I’m just looking for what, uh, what really works.

All right. So here are two, two good questions. So you’ve mentioned that conditions have not materially changed despite recent economic data. Do you still expect to see, uh, interest rates a fair bit lower over the next 12 to 18 months? I still do. If we can get out of this dusty environment, look, the I I I’ve highlighted, look, you gotta look at, look at the horizon and look at the through line.

And when we’re having a bunch of uncertainties that are about things that will increase prices, it’s just throwing lots and lots of dust in the air and it’s hard to see the through line. I still think that underneath there. Is a robust, healthy economy with employment, pretty much stable at full employment, inflation headed back to 2% GDP growth, solid and strong.

And we can get back to the resting point of normal. Um, in, in that kind of environment if we’re gonna have an escalating. F trade war that leads to higher prices and a stagflationary kind of environment where GDP growth is falling. I could revise, um, I, I could revise my, my economic outlook, but I still think if we can get past this dusty part over 12 to 18 months.

The SAP dot plot tells you that the vast majority of members of the committee believe that the ultimate settling point for rates is well below where we are today. And so I still think that, that we can get there. And our final question, I, I love your self description. You have said, I’m neither a hawk nor a dove.

I’m a data dog, so now we have to add That’s right. Hawks. I don’t like birds. I don’t wanna Dogs haw, stuss and dogs. So, explain, um, how you as a data dog, how does that affect your approach to monetary policy, especially in 2025, where you are a voting member? I, it, I try to get out there. Uh, the, the first rule of the Datadog kennel.

Is that there’s a time for walking and there’s a time for sniffing and know the difference and the time for sniffing is exactly when there is not clarity. Okay? And that is go get every data series you can, every frequency. Don’t throw anything away. If you can get private sector price information, get it.

If you are looking at the job market, don’t just look at payroll employment when. There’s a bunch of stuff with population growth and immigration that make it noisier. Don’t just look at the unemployment rate. When labor force participation changes can, can affect it. Take ratios of unemployment to vacancies.

Look at the hiring weight and the quit rate. Get out and talk to the business people in, in our regions and the kind of information that goes into the base book. All of those things are more real time than just the data series, but that mentality that if you, if you have a question, get out there and sniff.

That’s the essence of the Datadog credo. If, if, if you wanna and look, it comes with some downsides. Um, if you are more theoretical, ideological, there are times when you might be right and, and you can get to the answer quicker, but. This seems like a very uncertain environment. Unusual, unprecedented business cycles, nothing like things we’ve seen before.

So just personally I’m more comfortable with, with that kind of approach. Hmm. Real really fascinating stuff. Thank you, Austin, for being so generous with your time. 1149 and 30 seconds. I don’t wanna make you late. Whenever you wanna do the second, I’m a big fan and, and well thank you. It’s a real treat for me.

Thank you. Very. So whenever we wanna do another one of these, we can talk about monetary policy, we can talk about whatever. Happy to schedule it at your convenience anytime. And we’ll run it whenever. That’s great. Alrighty, that’s great. Thank you so much. Talk to you later. We’ll talk to you soon and I’ll, I’ll record the intros and outros now and we’ll do that.

Thank you. Austin Ya. All right, so I’m gonna end the. I’m gonna end this. I’m just gonna shut this, uh, here, and then we’ll just keep recording. Leave meeting, uh, no, no. Zoom market. Go away. All right, so I’m gonna record an outro. This is gonna be a tough one to edit. Are you gonna do it or is, uh, Colin or Bob?

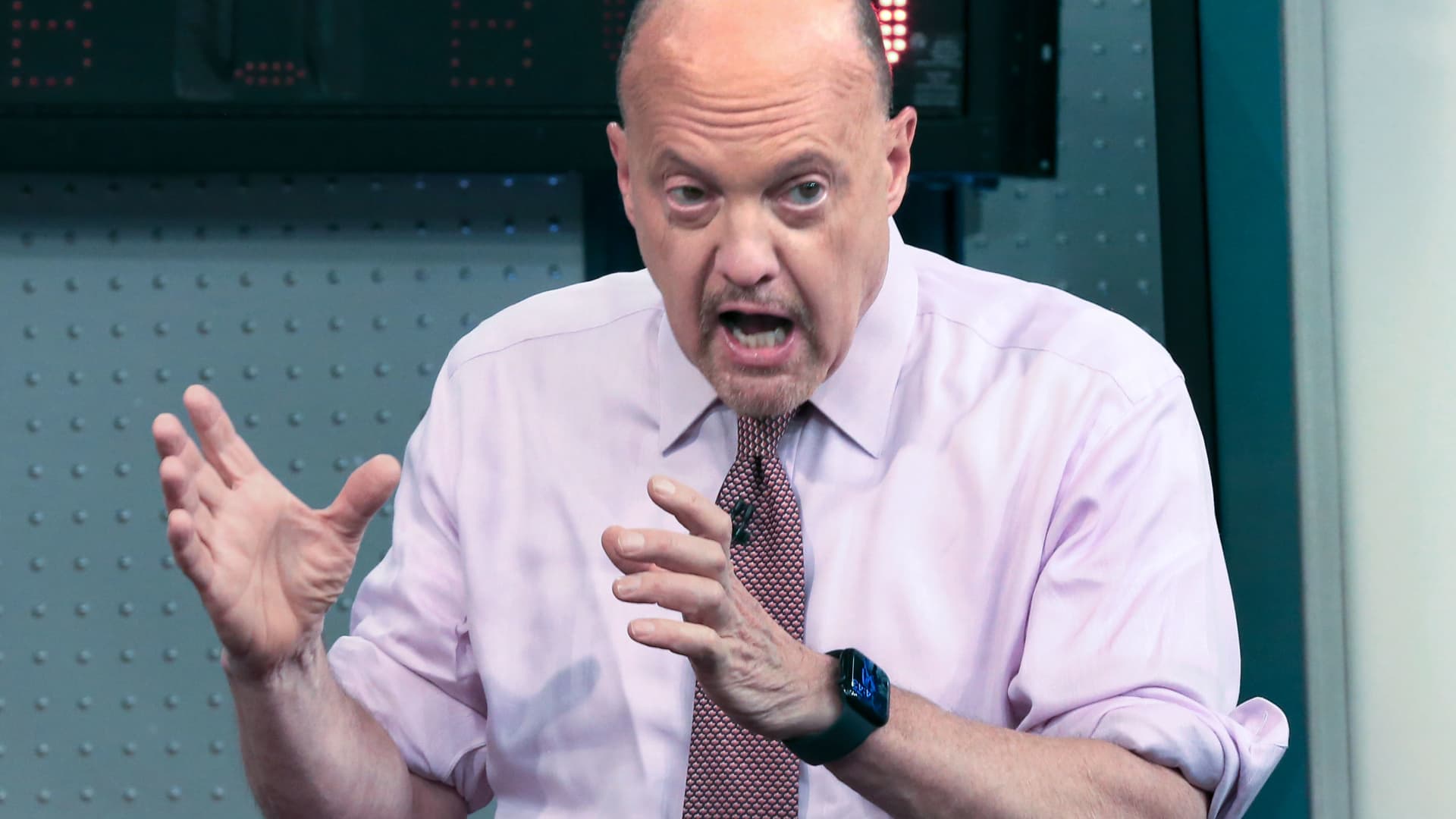

All right, I’ll, I’ll circle back to her. So, to wrap up. If you’re an investor interested in what’s going on in the economy, looking at inflation, looking at monetary policy, it’s simply not as black and white As you often hear about, uh, many of the voting members of the FOMC, uh, look at the data that’s out there as complex and not binary.

Uh, there are a lot of moving parts. Don’t think that what you’re hearing in these headline, um, reports are remotely giving you the full color of what’s happening. There are obviously a whole lot of moving parts here, uh, a lot of complexity, and it’s reassuring when you hear from people like. Chicago Federal Reserve President and FOMC, voting member Austin Gouldsby, who are data driven, who do focus on filtering out the noise, but paying attention to the most recent trends, but following the through line.

It’s not simple, it’s complicated. We really need to bring a more intelligent approach than we often see. Uh, when. In as investors, we think about. What the federal reserve’s gonna be, what’s gonna happen, what the Federal Reserve is gonna do in response to what inflation is doing. Uh, perhaps if we had a little more sophisticated approach and a little less binary, we wouldn’t see people being so wrong about when the Fed’s gonna cut, when a recession is gonna happen.

What’s going on overall with the robustness of the economy. Hey, it turns out that. Economics is hard. It’s complicated. There are lots of moving parts. We oversimplify this at our own, uh, risk. I’m Barry Ritholtz. You’ve been listening to Bloomberg’ At The Money.

~~~

Find our entire music playlist for At the Money on Spotify.

The post At the Money: Austan Goolsbee, Chicago Fed President on Tariffs, Inflation and Monetary Policy appeared first on The Big Picture.