AI on the farm: The startup helping farmers slash losses and improve cows’ health

The U.K. company CattleEye found that a single camera posted four meters above dairy cows can identify health issues before they become a big problem—saving money and the planet along the way.

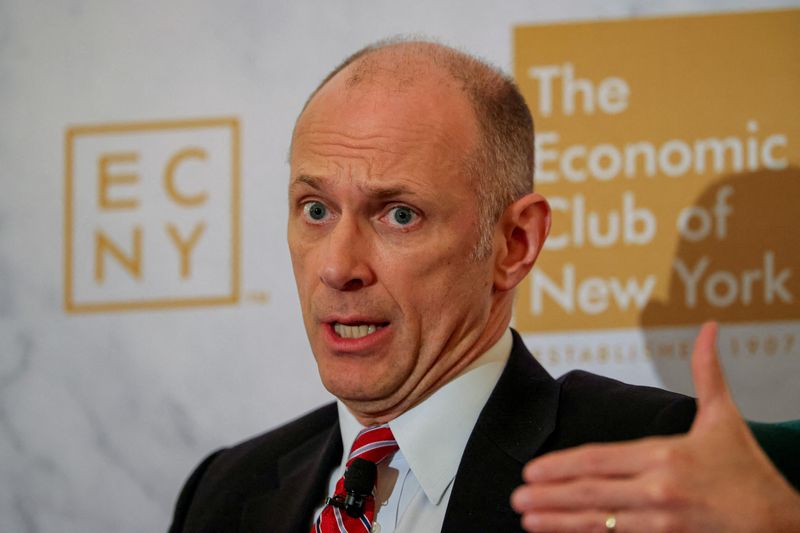

Having grown up on a small dairy farm in County Armagh, Northern Ireland, Terry Canning was well aware that dairy cows were vital to his upbringing—but they weren’t meant to be his future.

Instead, Canning was “shipped off to academia,” he tells Fortune, where he studied engineering for four years. After graduation, he worked for a number of computing companies. Then, in 2004 at age 30, Canning decided to return to his family home and set up his own company—developing a software product for managing livestock.

The idea of animal analytics was hugely important within the agricultural industry at the time, because of recent outbreaks of foot-and-mouth disease, highlighting the risks of not keeping records of animal movements.

To solve that problem, the initial idea was to attach devices to animals—as Canning describes it, a kind of “Fitbit for cows,” but that turned out to be expensive and tricky to do. Batteries would run out, or ear tags could get caught and removed as a cow moved through a farm.

Canning thought there must be another way—and he found it with the help of his cofounder, Adam Askew. Askew was a researcher looking at computer vision for medical purposes, such as cancer detection. Together, they had a eureka moment: Why couldn’t they use the same tech to watch cows? They devised a system to watch as the cattle passed beneath a camera, using computer vision to analyze how healthy cows are, and particularly whether they were limping.

“We’re addressing the lameness issue, which is a big issue at lots and lots of dairies,” says Canning. “They reckon 30% of all cows don’t walk as well as they should do.” That has an economic impact since immobile cows are culled: Canning points to U.K. data suggesting cattle lameness results in £142 million ($190 million) of losses there. And there’s an environmental impact, too: Shortening the milk-producing years of cows means more animals are needed, which makes the industry more resource-intensive and greenhouse-gas-emitting.

The company became CattleEye, and its core technology hasn’t changed all that much since its founding in 2019. An AI eye—a simple camera—sits above the route dairy cows take on a farm daily. As each cow passes beneath its scope of vision, it’s identified based on its unique markings, and assessed for how well it’s walking. The camera identifies around 16 points on each animal, such as the ear, the back of the head, and the spine, then uses the shifting of those data points to analyze the cow’s gait. CattleEye’s AI is composed of advanced deep learning models that have been trained on data generated by veterinarians. The company has a trove of around 100,000 videos of cows that have been annotated and scored by veterinarians for observed health, and are used for training the models.

When the system is in use, the AI gives each cow a score between 0 and 100: Any cow scored at over 50 is deemed to be lame, and worthy of a checkup by the farmer, who accesses the data on his herd through a web app. CattleEye can identify lame cows four weeks earlier than most humans, Canning says, thanks to its machine-learning-powered analysis.

CattleEye typically costs farmers about $1.45 per cow per month but can deliver “at least a 10x return,” says Canning; it also slashes lameness by roughly 10 percentage points and cuts emission intensity by up to 40% by increasing the lifespan of cows. The science behind CattleEye has also been evaluated by independent scientific studies, which came to similar conclusions.

The setup costs are kept low by using off-the-shelf products to avoid scaring off farmers with high upfront charges. The AI system is a patented and complicated process, but the hardware involved consists of a simple, mass-produced camera posted at least four meters above the ground where the cows walk, as well as an Ethernet switch and an SD card. And because cows can’t be trusted to queue single file, the system works even if multiple animals walk underneath the camera at once.

One of CattleEye’s earliest commercial customers was U.K. supermarket chain Tesco. Tom Atkins, agriculture manager at Tesco, says the company has been working with CattleEye since 2019. “It’s a key part of ensuring our customers who buy our milk know our farmers are fairly treated and their cows are well cared for,” he tells Fortune.

Tesco’s early, enthusiastic adoption of CattleEye’s technology helped land seed funding of £500,000 ($672,900) from the Belfast-based venture capital fund Techstart. (Further funding included a $2.5 million round in 2021.) The company launched a pilot project in 2020 at three dairy farms outside Cheshire in the U.K., where a veterinarian would go along every week and rate the cows’ health over time as the cameras watched, too. “That became our ground truth data,” says Canning.

Today, CattleEye is a digital custodian for more than 200,000 cows worldwide, with an increasing U.S. customer base after German food technology supplier GEA Group acquired the company in March 2024. (Canning declined to share financial details about the acquisition, other than to say that the deal has helped resource up CattleEye and helped with “not having to worry about cash anymore” to grow the company.) Clients include the Dutch-based A-ware Food Group, Danone, and global dairy giant Arla.

Next on the road map for CattleEye is to try to find other uses for the same technology. The company has already completed a pilot project with poultry, in an attempt to measure their well-being, but didn’t end up commercializing it. “A lot of this technology is used in other sectors already,” says Canning. “The dairy industry isn’t the forerunner in all of this. You’re looking at stuff around the military and autonomous cars, where a lot of the innovation comes from, and we’re just reapplying the technology and learning from it.”

Because GEA is a significant data holder, focused on the dairy industry, Canning can foresee a future where GEA’s data and CattleEye’s AI expertise could be combined to produce specific advice on how and when it’s best to milk a particular cow. Other insights could include when a cow is calving and how well they’re eating. “It’s great to be having an impact in bringing about a better planet, feeding more people, and giving them more nutrition in a more sustainable way,” says Canning.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com