Alternative Investments: Big Promises, Questionable Payoffs!

Many a slip between the cup and the lip!

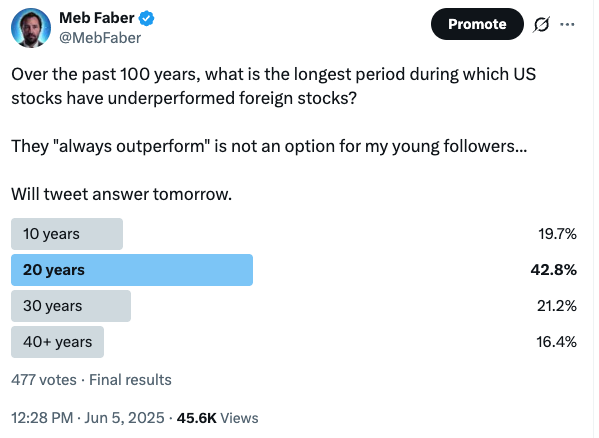

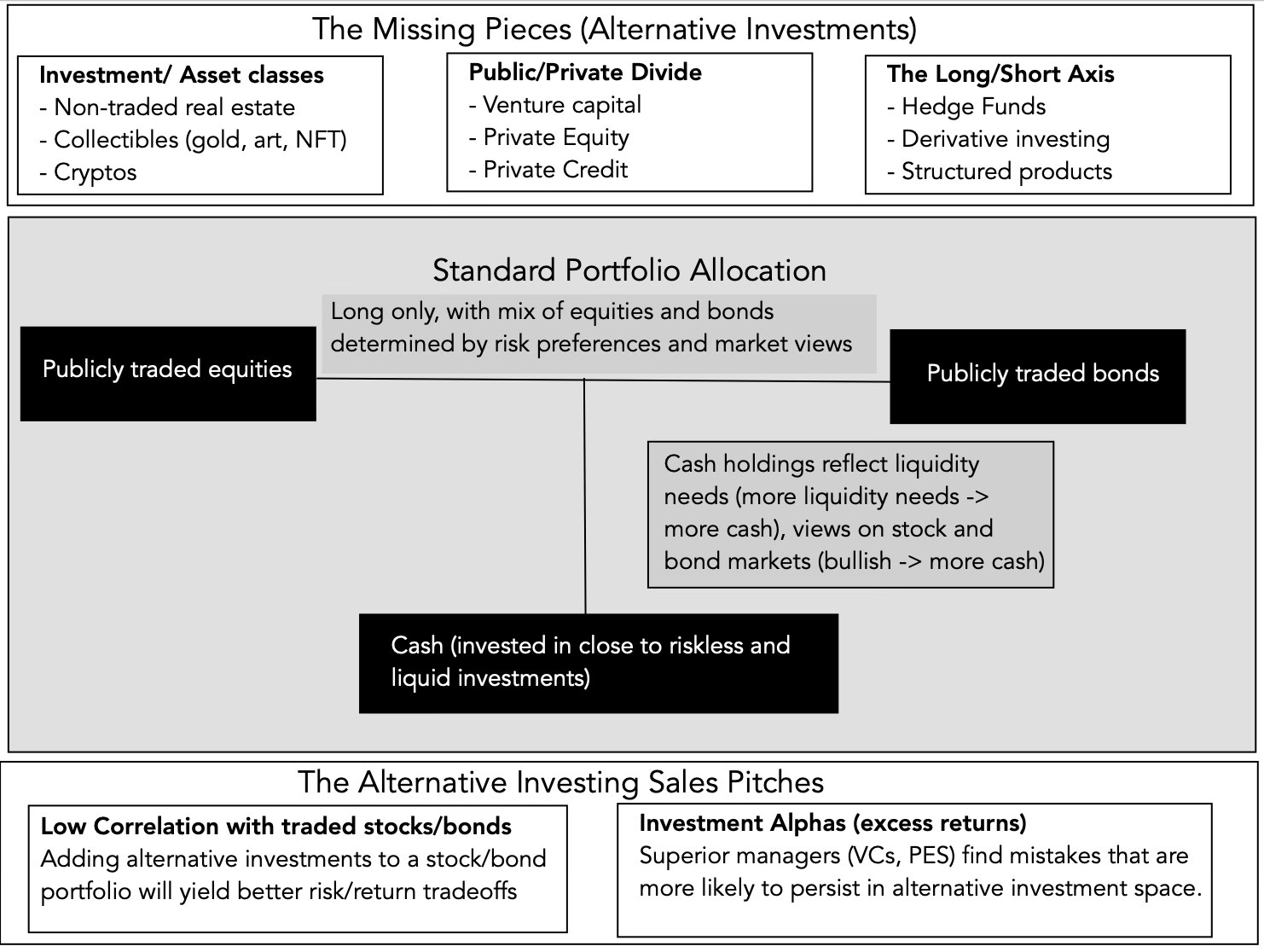

It is true that most investing lessons are directed at those who invest only in stocks and bonds, and mostly with long-only strategies. It is also true that in the process, we are ignoring vast swaths of the investment universe, from other asset classes (real estate, collectibles, cryptos) to private holdings (VC, PE) to strategies that short stocks or use derivatives (hedge funds). These ignored investment classes are what fall under the rubric of alternative investments, and while many of these choices have been with us for as long as we have had financial markets, they were accessible to only a small subset of investors for much of that period. In the last two decades, alternative investments have entered the mainstream, first with choices directed at institutional investors, but more recently, in offerings for individual investors. Without giving too much away, the sales pitch for adding alternative investments to a portfolio composed primarily of stocks and bonds is that the melding will create a better risk-return tradeoff, with higher returns for any given risk level, albeit with two different rationales. The first is that they have low correlations with financial assets (stocks and bonds), allowing for diversification benefits and the second is investments in some of these alternative asset groupings have the potential to earn excess returns or alphas. While the sales pitch has worked, at least at the institutional level, in getting buy-in on adding alternative investments, the net benefits from doing so have been modest at best and negative at worst, raising questions about whether there need to be more guardrails on getting individual investors into the alternative asset universe.

The Alternative Investment Universe

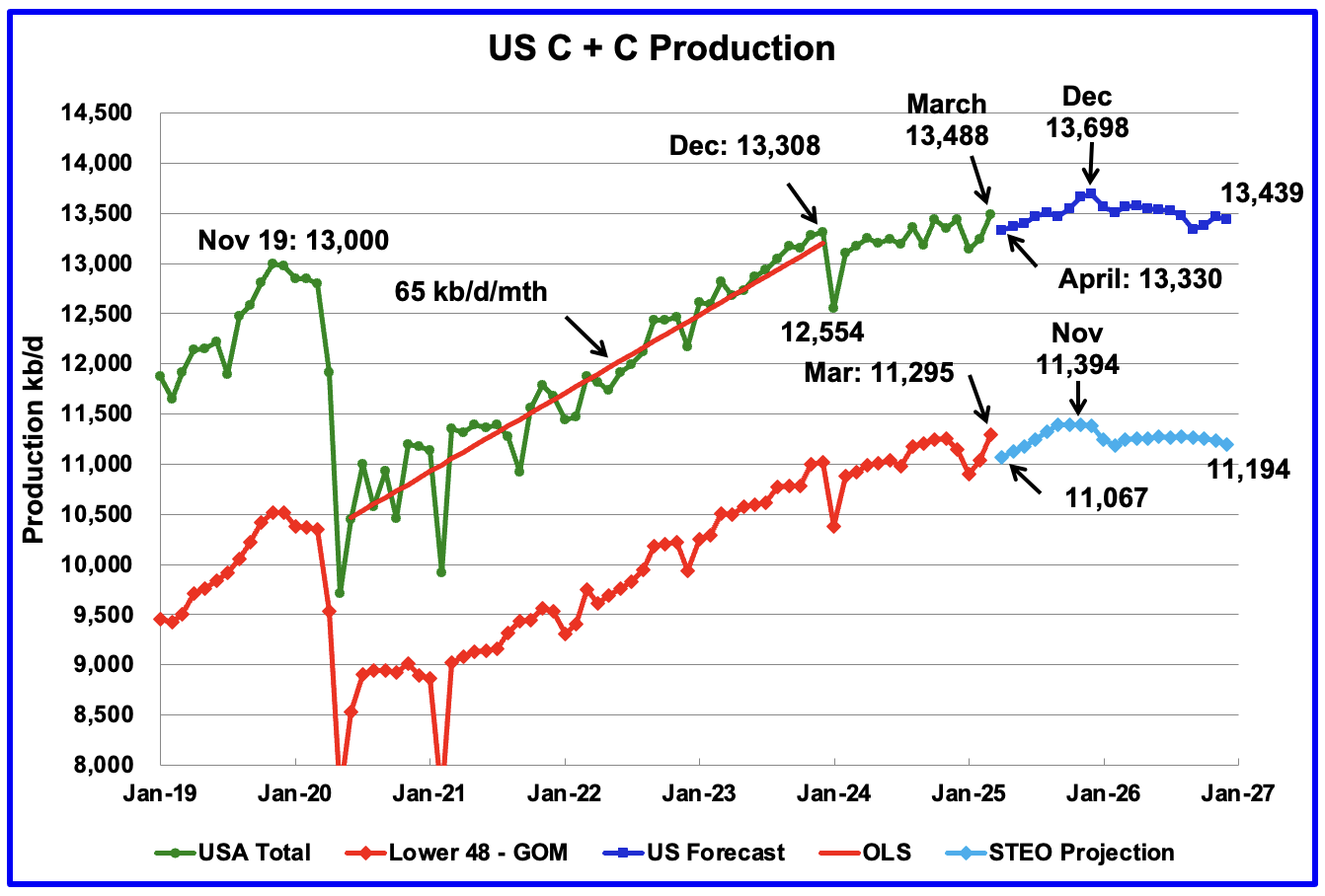

The use of the word "alternative" in the alternative investing pitch is premised on the belief that much of investing advice is aimed at long-only investors allocating their portfolios between traded stocks, bonds and cash (close to riskless and liquid investments). In that standard investment model, investors choose a stock-bond mix, for investing, and use cash as a buffer to bring in not only liquidity needs and risk preferences, but also views on stock and bond markets (being over or under priced):

The mix of stocks and bonds is determined both by risk preferences, with more risk taking associated with a higher allocation to stocks, and market timing playing into more invested in stocks (if stocks are viewed as under priced) or more into bonds (if stocks are over priced and bond are viewed as neutral investments).

This framework accommodates a range of choices, from the purely mechanical (like the much touted 60% stocks/40% bonds mix) to more flexible, where allocations can vary across time and be a function of market conditions. This general framework allows for variants, including different view on markets (from those who believe that markets are efficient to stock pickers and market timers) as well as investors with very different time horizons and risk levels. However, there are clearly large segments of investing that are left out of this mix from private businesses (since they are not listed and traded) to short selling (where you can have negative portfolio weights not just on individual investments but on entire markets) to asset classes that are not traded. In fact, the best way to structure the alternative investing universe if by looking at alternatives through the lens of these missing pieces.

1. Long-Short

In principle, there is little difference between being long on an investment and holding a short position, with the only real difference being in the sequencing of cash flows, with the former requiring a negative cash flow at the time of the action (buying the stock or an asset) and a positive cash flow in a subsequent period (when it is sold), and the latter reversing the process, with the positive cash flow occurring initially (when you sell a stock or an asset that you do not own yet) and the negative cash flow later. That said, they represent actions that you would take with diametrically opposite views of the same stock (asset), with being long (going short) making sense on assets where you expect prices to go up (down). In practice, though, regulators and a subset of investors seem to view short selling more negatively, often not just attaching loaded terms like "speculation" to describe it, but also adding restrictions of how and when it can be done.

Many institutional investors, including most mutual, pension and endowment funds, are restricted from taking short positions on investments, with exceptions sometimes carved out for hedging. For close to a century, at least in the United States, hedge funds have been given the freedom to short assets, and while they do not always use that power to benefit, it is undeniable that having that power allows them to create return distributions (in terms of expected returns, volatility and other distributional parameters) that are different from those faced by long-only investors. Within the hedge fund universe, there are diverse strategies that not only augment long-only strategies (value, growth) but also invest across multiple markets (stocks, bonds and convertibles) and geographies.

The opening up of derivatives markets has allowed some investors to create investment positions and or structured products that use options, futures, swaps and forwards to create cash flow and return profiles that diverge from stock and bond market returns.

2. Public-Private

While much of our attention is spent on publicly traded stocks and bonds, there is a large segment of the economy that is composed of private businesses that are not listed or traded. In fact, there are economies, especially in emerging markets, where the bulk of economic activity occurs in the private business space, with only a small subset of businesses meeting the public listing/trading threshold. Many of these private businesses are owned and funded by their owners, but a significant proportion do need outside equity capital, and historically, there have been two providers:

For young private businesses, and especially those that aspire to become bigger and eventually go public, it is venture capital that fills the void, covering the spectrum from angel financing for idea businesses to growth capital for firms further along in their evolution. From its beginnings in the 1950s, venture capital has grown bigger and carries more heft, especially as technology companies have come to dominate the market in the twenty first century.

For more established private businesses, some of which need capital to grow and some of which have owners who want to cash out, the capital has come from private equity investors. Again, while private equity has been part of markets for a century or more, it has become more formalized and spread its reach in the last four decades, with the capacity to raise tens of billions of dollars to back up deal making.

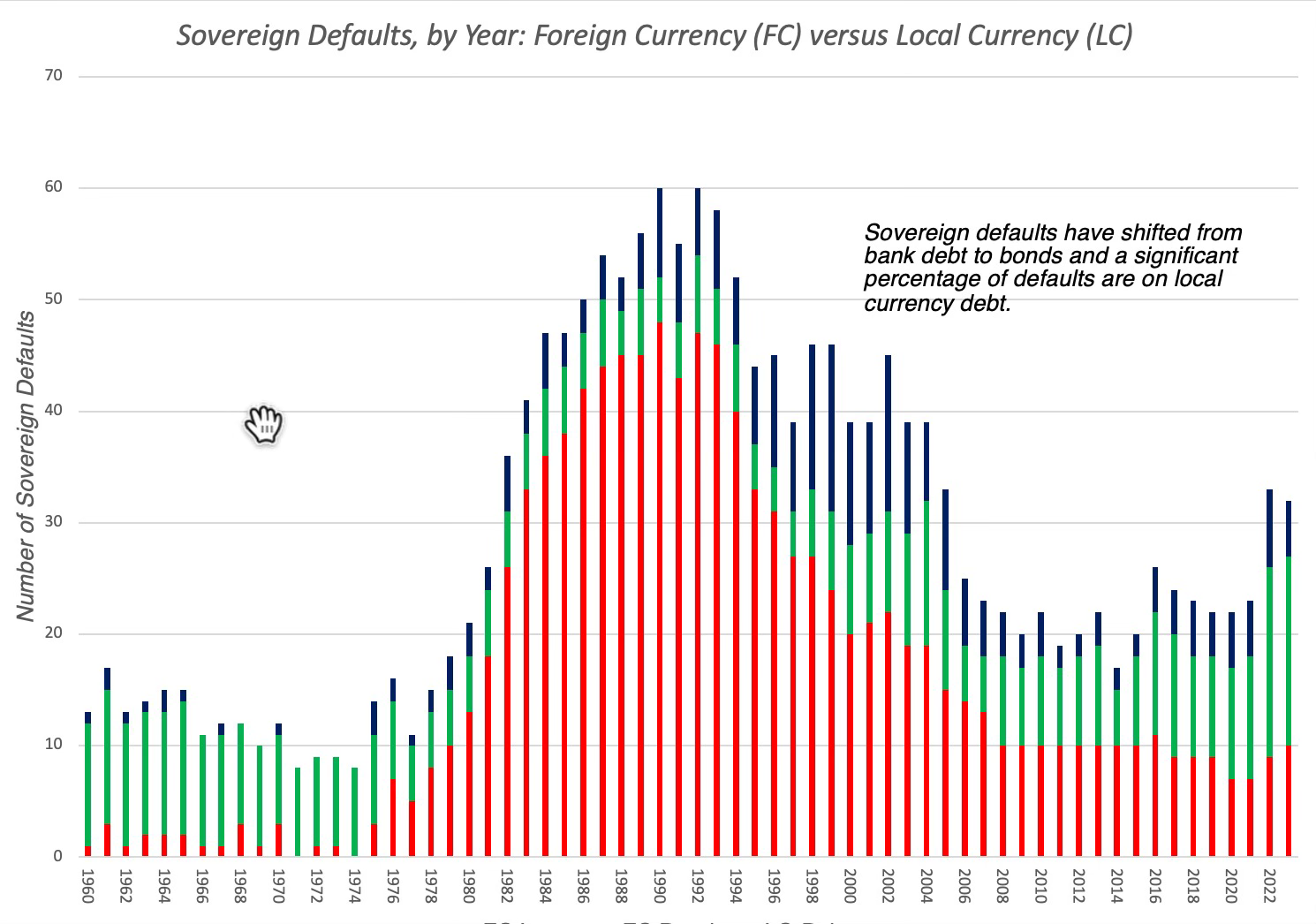

On the debt front, the public debt and bank debt market is supplemented by private credit, where investors pool funds to lend to private businesses, with negotiated rates and terms. again a process that has been around a while, but one that has also become formalized and a much larger source of funds. Advocates for private credit investing argue that it can be value-adding partly because of the borrower composition (often cut off from other sources of credit, either because of their size or default history) and partly because private credit providers can be more discerning of true default risk. Even as venture capital, private equity and private credit have expanded as capital sources, they remained out of reach for both institutional and individual investors until a couple of decades ago, but are now integral parts of the alternative investing universe.

3. Asset classes

Public equity and debt, at least in the United States, cover a wide spectrum of the economy, and by extension, multiple asset classes and businesses, but there are big investment classes that are either underrepresented in public markets or missing.

Real estate: For much of the twentieth century, real estate remained outside the purview of public markets, with a segmented investor base and illiquid investments, requiring localized knowledge. That started to change with the creation of real estate investment trusts, which securitized a small segment of the market, creating liquidity and standardized units for public market investors. The securitization process gained stream in the 1980s with the advent of mortgage-backed securities. Thus, real estate now has a presence in public markets, but that presence is far smaller than it should be, given the value of real estate in the economy.

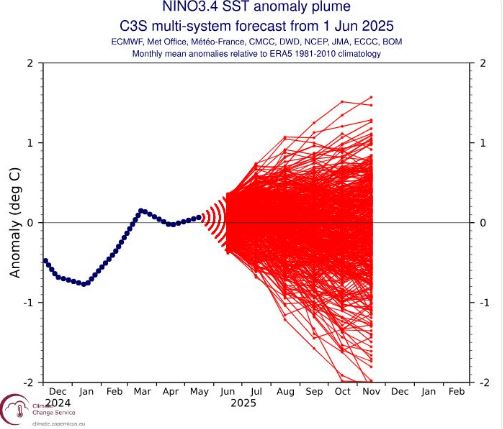

Collectibles: The collectible asset class spans an array of investment, most of which generate little or no cash flows, but derive their pricing from scarcity and enduring demand. The first and perhaps the longest standing collectible is gold, a draw for investors during inflationary period or when they lose faith in fiat currencies and governments. The second is art, ranging from paintings from the masters to digital art (non-fungible tokens or NFTs), that presumably offers owners not just financial returns but emotional dividends. At the risk of raising the ire of crypto-enthusiasts, I would argue that much of the crypto space (and especially bitcoin) also fall into this grouping, with a combination of scarcity and trading demand determining pricing.

Institutional and individual investors have dabbled with adding these asset classes to their portfolios, but the lack of liquidity and standardization and the need for expert assessments (especially on fine art) have limited those attempts.

The Sales Pitch for Alternatives

The strongest pitch for adding alternative investments to a portfolio dominated by publicly traded stocks and bonds comes from a basic building block for portfolio theory, which is that adding investments that have low correlation to the existing holdings in a portfolio can create better risk/return tradeoffs for investors. That pitch has been supplemented in the last two decades with arguments that alternative investments also offer a greater chance of finding market mistakes and inefficiencies, partly because they are more likely to persist in these markets, and partly because of superior management skills on the part of alternative investment managers, particularly hedge funds and private equity.

The Correlation Argument

Much of portfolio theory as we know it is built on the insight that combining two investments that are not perfectly correlated with each other can yield mixes that deliver higher returns for any given level of risk than holding either of the investments individually. That argument has both a statistical basis, with the covariance between the two investments operating as the mechanism for the risk reduction, and an economic basis that the idiosyncratic movements in each investment can offset to create a less risky combination.

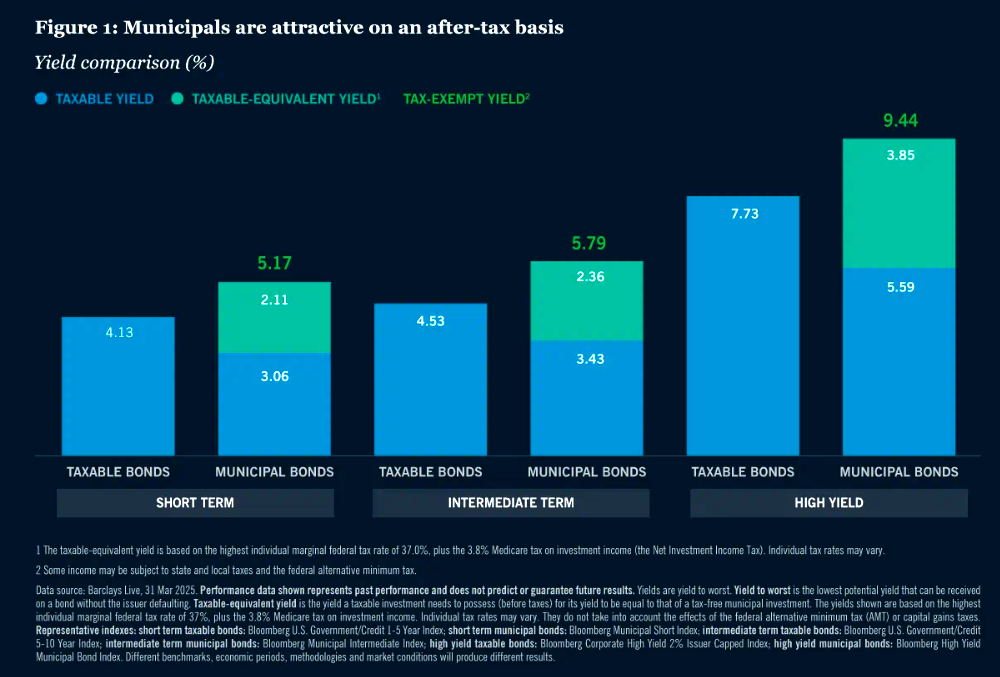

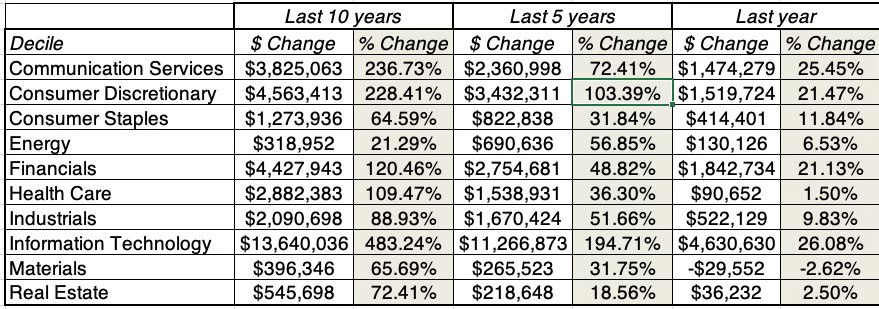

In that vein, the argument for adding alternative investments to a portfolio composed primarily of stocks and bonds rests on a correlation matrix of stocks and bonds with alternative investments (hedge funds, private equity, private credit, fine art, gold and collectibles):

Guggenheim Investments

While the correlations in this matrix are non-stationary (with the numbers changing both with time periods used and the indices that stand in for the asset classes) and have a variety of measurement issues that I will highlight later in this post, it is undeniable that they at least offer a chance of diversification that may not be available in a long-only stock/bond portfolio.

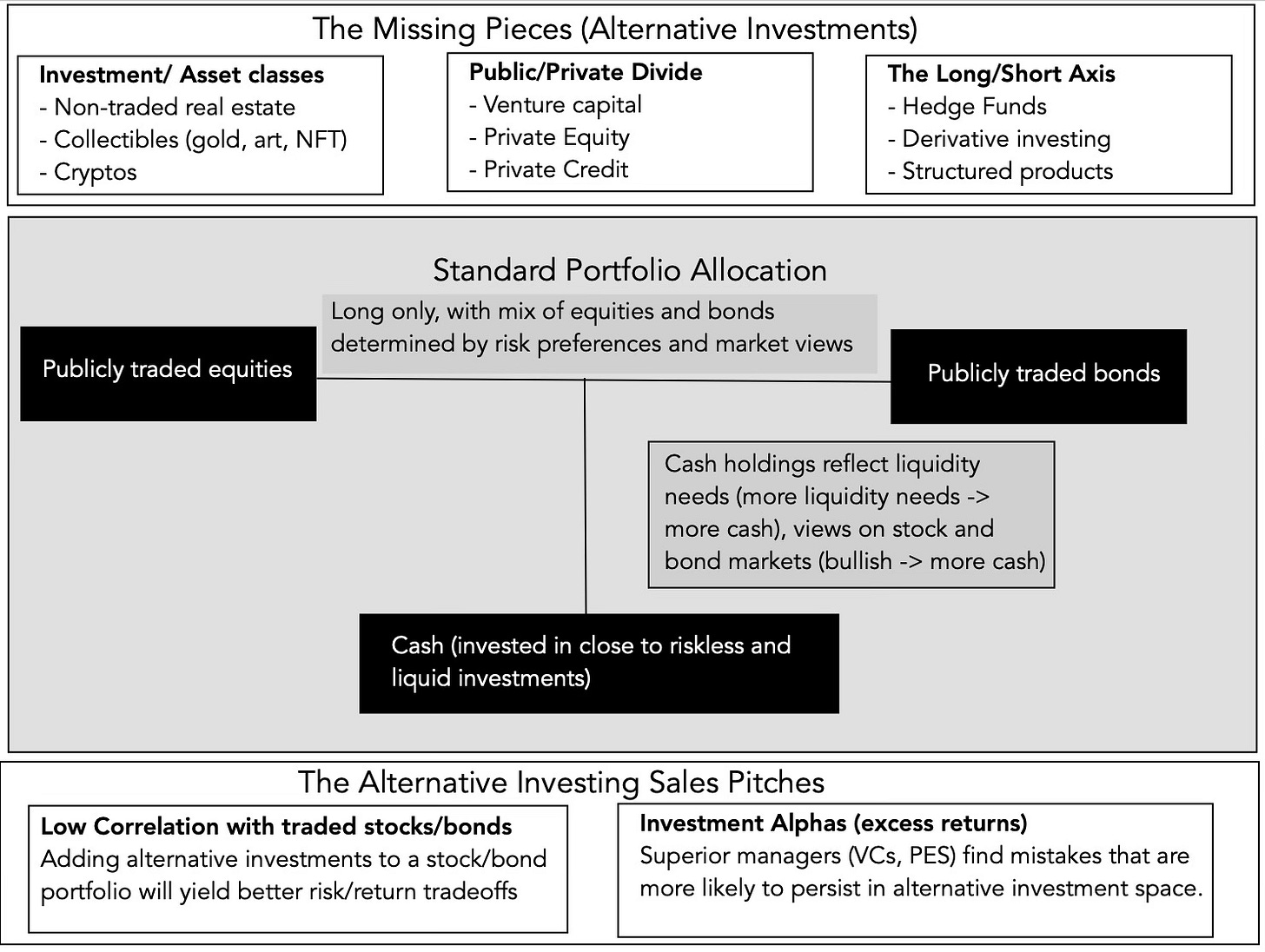

Using historical correlations as the basis, advocates for alternative investments are able to create portfolios, at least on paper, that beat stock/bond combinations on a risk/return tradeoff, as can be see in this graph:

EquityMultiple Investment Partners, Green Street Advisors, and JPMorgan Asset Management

Note that the comparison is to a portfolio composed 60% of stocks and 40% of bonds, a widely used mix among portfolio managers, and in each of the cases, adding alternative investments to that portfolio results in a mix that yields higher returns with lower risk.

The Alternative Alpha Argument

The correlation-based argument for adding alternative investments to a portfolio is neither new nor controversial, since it is built on core portfolio theory arguments for diversification. For some advocates of alternative investments, though, that captures only a portion of the advantage of adding alternative investments. They argue that the investment classes from alternative investments draw on, which include non-traded real estate, collectibles and private businesses (young and old), are also the classes where market mistakes are more likely to persist, because of their illiquidity and opacity, and that alternative asset managers have the localized knowledge and intellectual capacity to find and take advantage of these mistakes. The payoff from doing so takes the form of "excess returns" which will supplement the benefits that flow from just diversification.

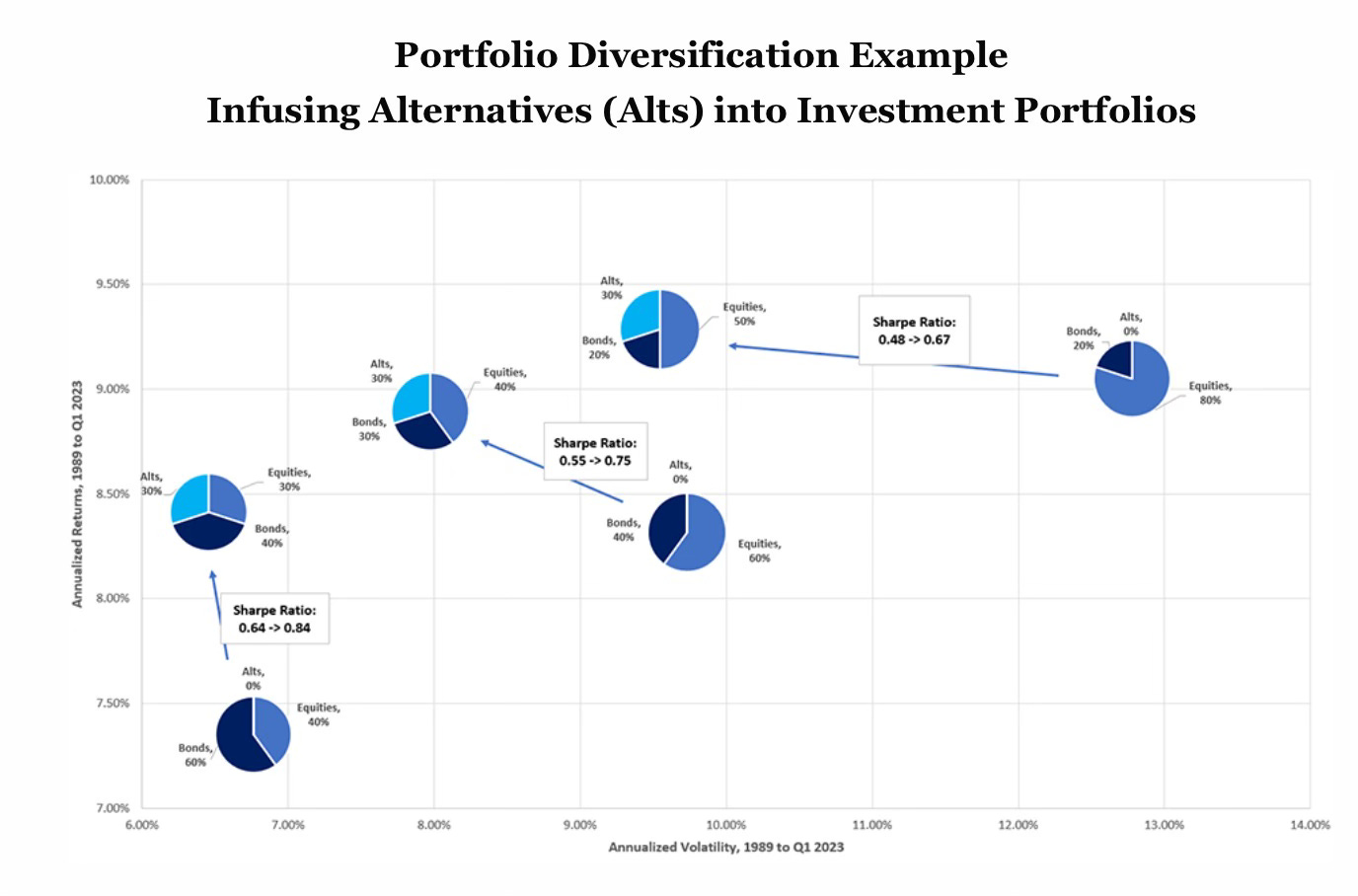

This alpha argument is often heard most frequently with those advocating for adding hedge funds, venture capital and private equity to conventional portfolios, where the perception of superior investment management persists, but is that perception backed up by the numbers? In the graph below, I reproduce a study that looks at looked at 20-year annualized returns, from 2003 to 2022, on many alternative asset classes:

Given the differences in risk across alternative investment classes, the median returns themselves do not tell us much about whether they earn excess returns, but two facts come through nevertheless. The first is that the variation across managers within investment classes is significant in both private equity and venture capital. The second, and this is not visible in this graph, is that persistence in outperformance is more common in venture capital and private equity than it is in public market investors, with winners more likely to continue winning and losers dropping out. I expanded on some of the reasons for this persistence, at least in venture capital, in a post from some years ago.

The bottom line is that there is some basis for the argument that as investment classes, hedge funds, private equity and venture capital, generate excess returns, albeit modest, relative to other investors, but it is unclear whether these excess returns are just compensation for the illiquidity and opacity that go with the investments that they have to make. In addition, given the skewed payoffs, where there are a few big and persistent winners, the median hedge fund, private equity investor or venture capitalist may be no better at generating alpha than the average mutual fund manager.

The Rise of Alternative Investing

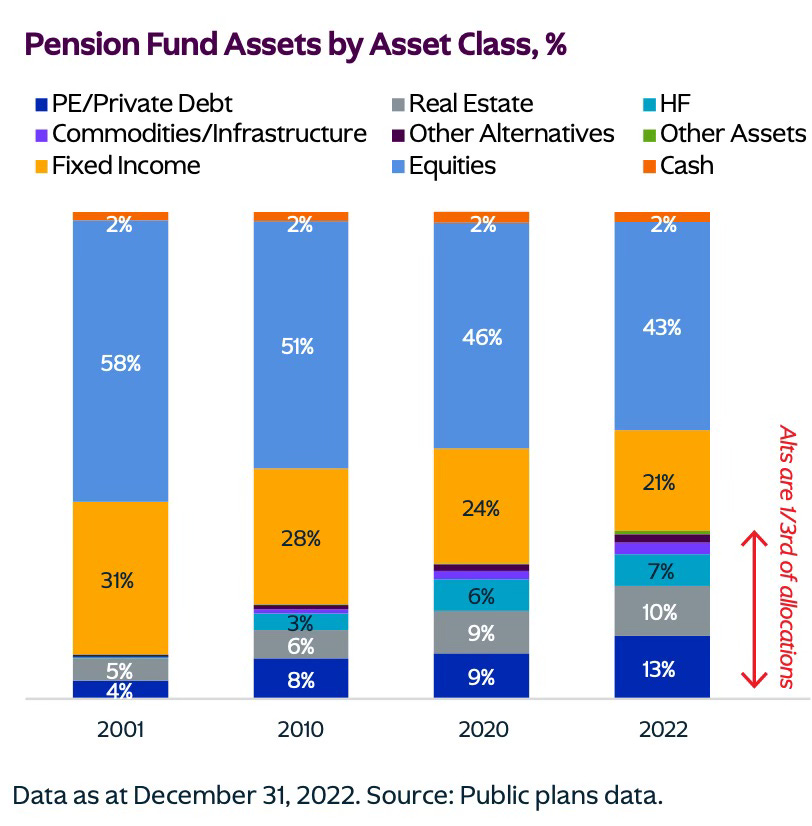

No matter what you think of the alternative investing sales pitch, it is undeniable that it has worked, at least at the institutional investor level, for some of its adopted, especially in the last two decades. In the graph below, for instance, you can track the rise of alternative investments in pension fund holdings in this graph (from KKR):

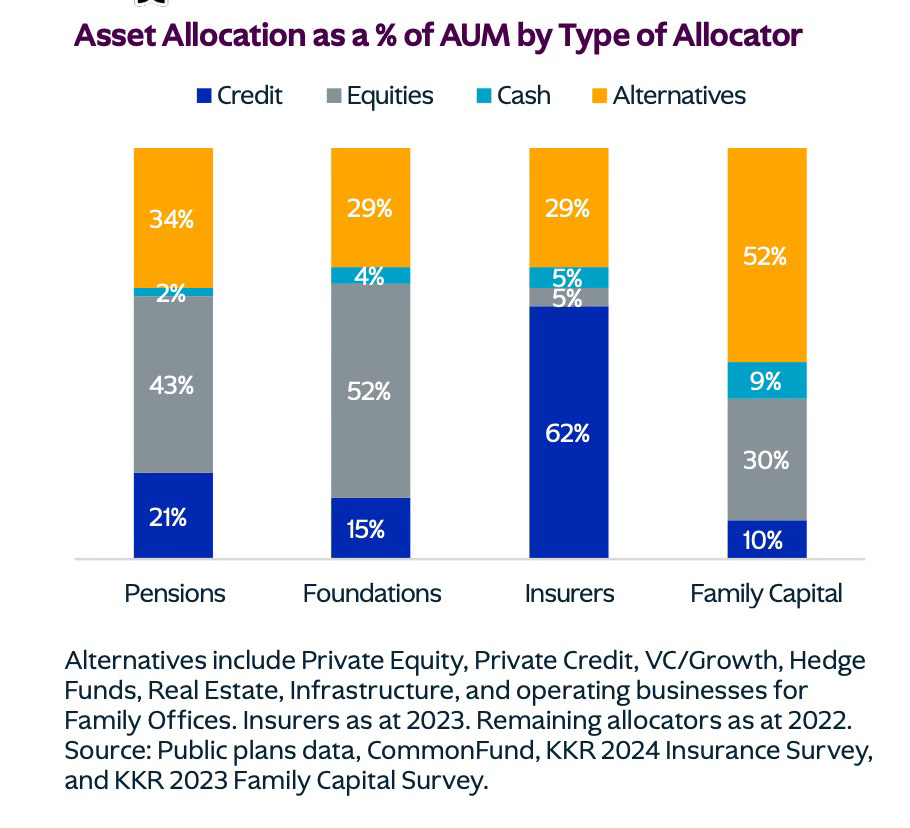

That move towards alternatives is not just restricted to pension funds, as other allocators have joined the mix:

Source: KKR

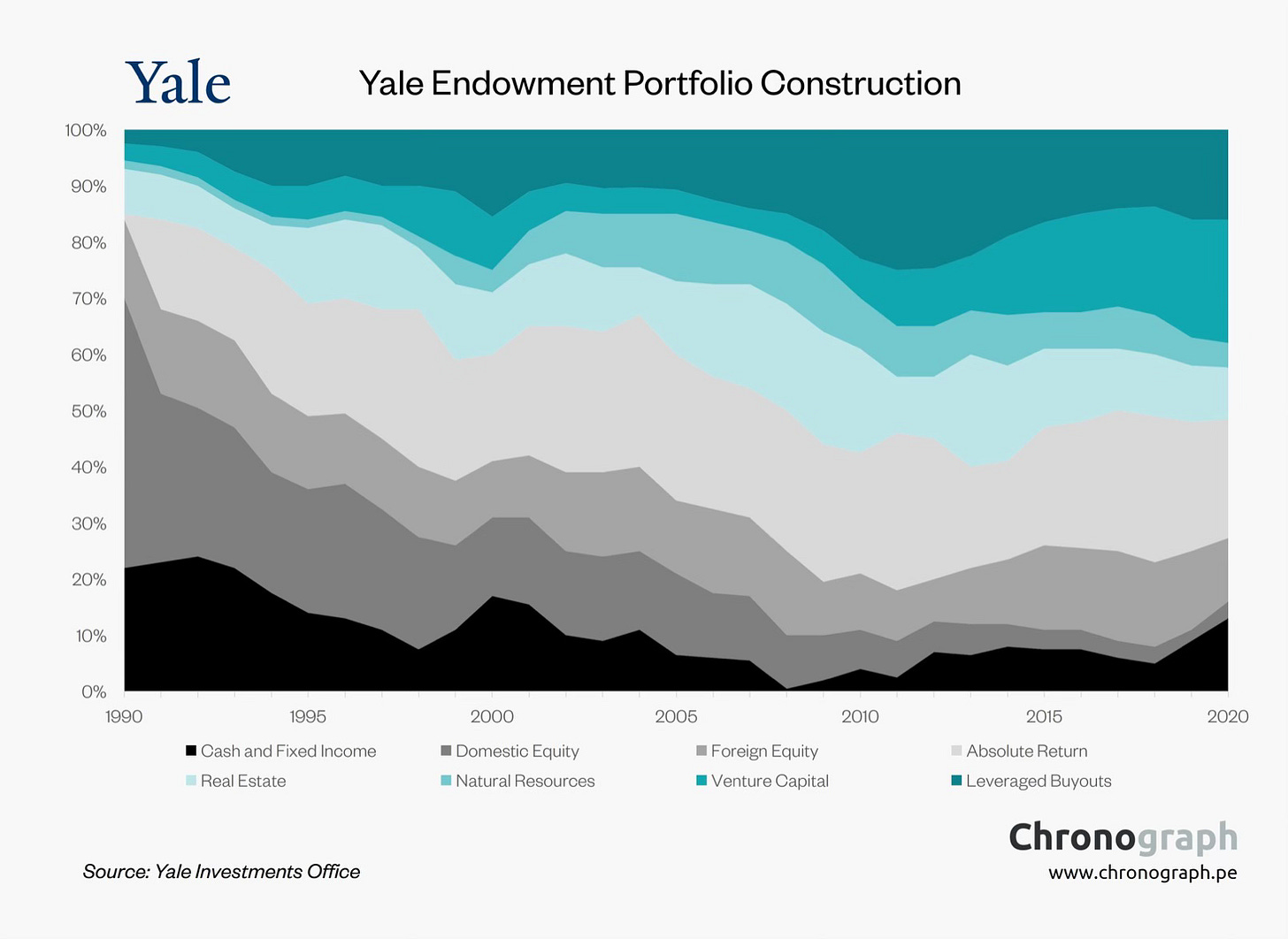

Some of the early movers into alternative asset classes were lauded and used as role models by others in the space. David Swensen, at Yale, for instance, burnished a well-deserved reputation as a pioneer in investment management by moving Yale's endowment into private equity and hedge funds earlier than other Ivy League schools, allowing Yale to outpace them in the returns race for much of this century:

As other fund managers have followed Yale into the space, that surge has been good for private equity and hedge fund managers, who have seen their ranks grow (both in terms of numbers and dollar value under management) over time.

Where's the beef?

As funds have increased their allocations to alternative investments, drawn by the perceived gains on paper and the success of early adopters, it is becoming increasingly clear that the results from the move have been underwhelming. In short, the actual effects on returns and risk from adding alternative investments to portfolios are not matching up to the promise, leading to questions of why and where the leakage is occurring.

The Questionable Benefits of Alternative Investing

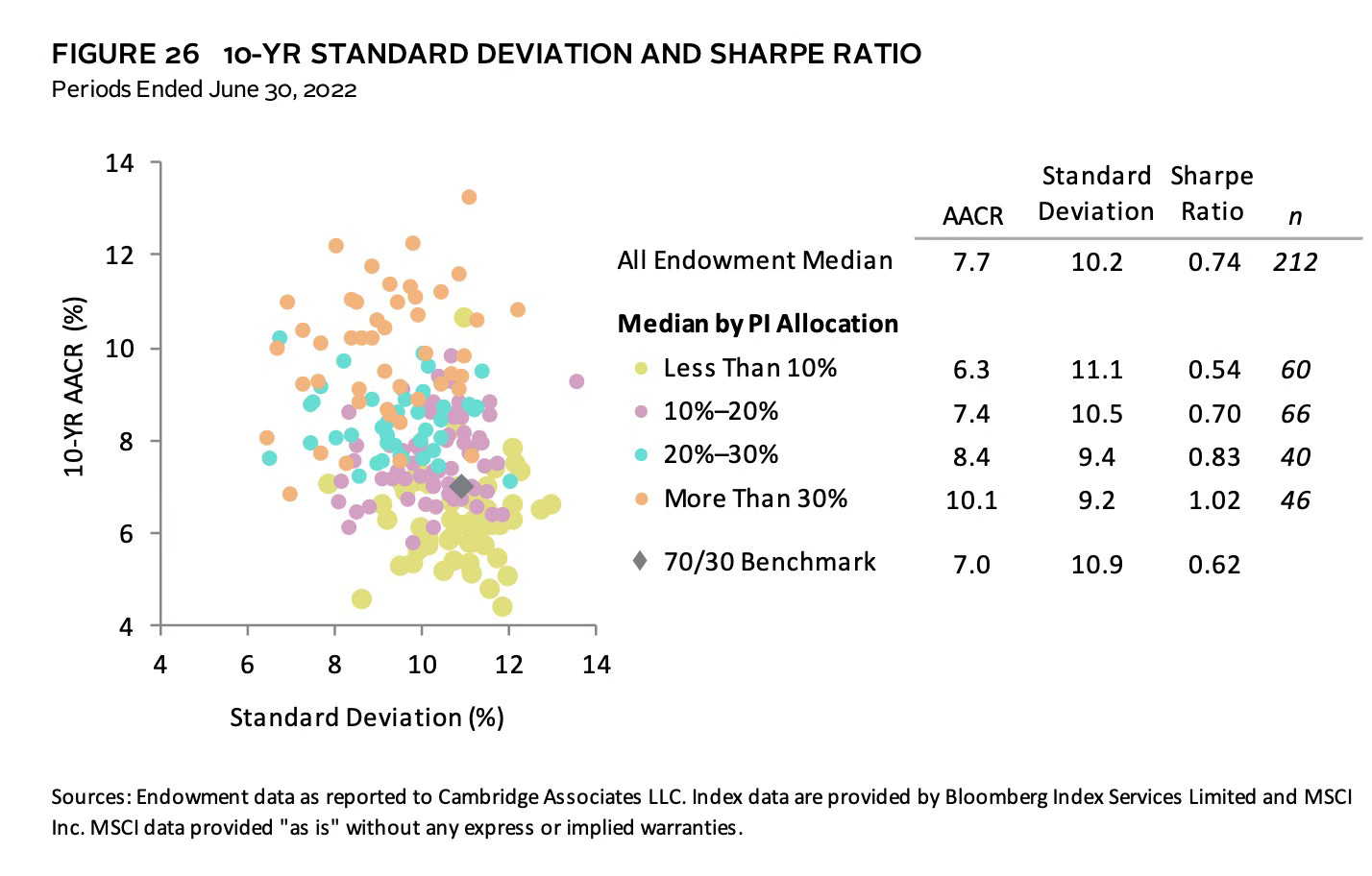

In theory and principle, adding investments from groupings of investments that are less correlated with stocks and bonds should yield benefits for investors, and at least in the aggregate, over long time periods that may hold. Cambridge Associates, in their annual review of endowments, presents this graph of returns and standard deviations, as a function of how much each endowment allocated to private investments over a ten-year period (from 2012-2022):

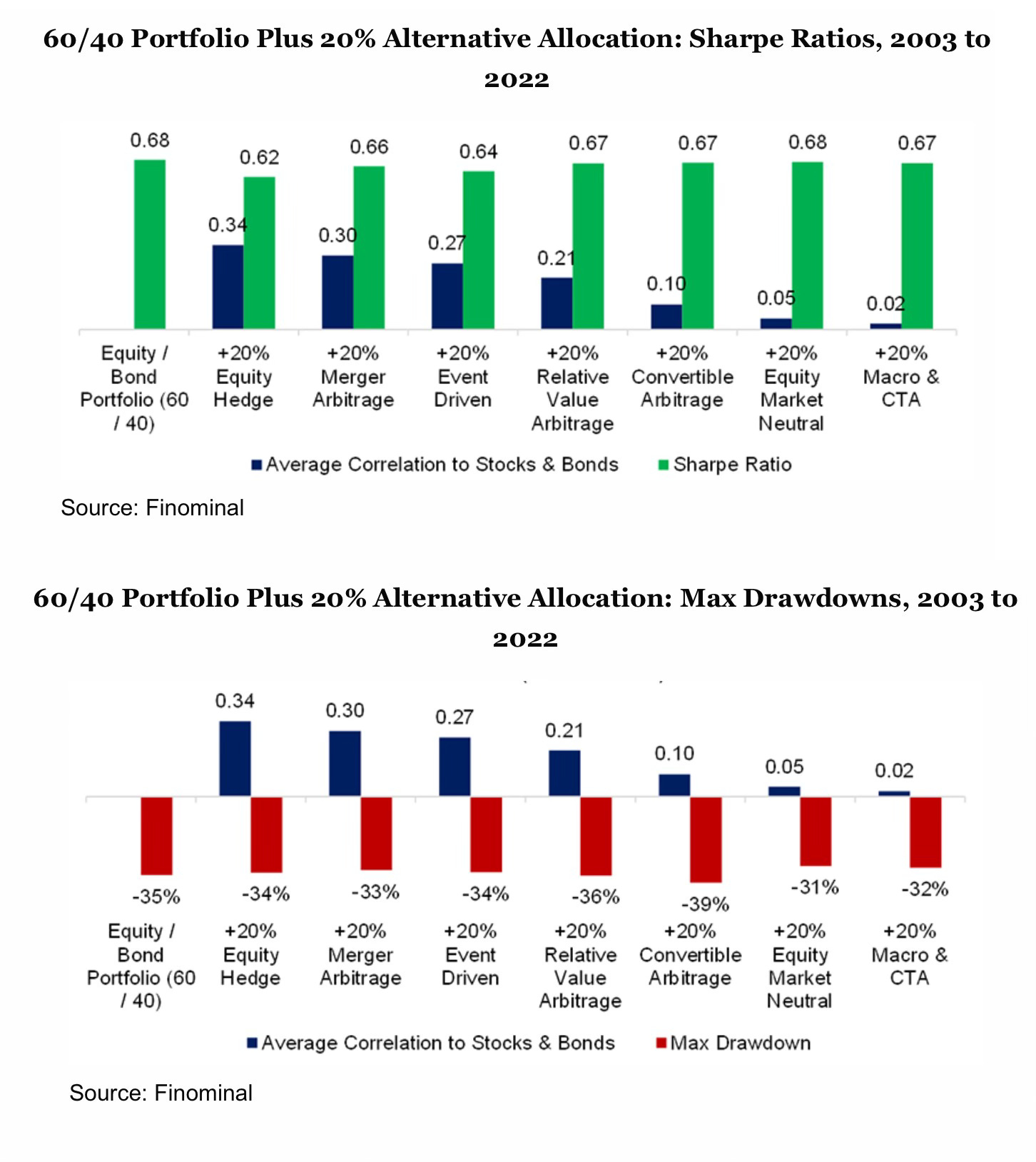

With the subset of endowments that Cambridge examined, both annual returns and Sharpe ratios were higher at funds that invested more in private investments (which incorporates much of the alternative investment space). Those results, though, have been challenged by others looking at a broader group of funds. In an article in CFA magazine, Nicolas Rabener looked at the two arguments for adding hedge funds to a portfolio, i.e., that they increase Sharpe ratios and reduce drawdowns in fund value during market downturns, and found both absent in practice:

Nicolas Ramener, CFA Institute

With hedge funds, admittedly just one component of alternative investing, Rabener finds that notwithstanding the low correlations that some hedge fund strategies have with a conventional equity/bond portfolio, there is no noticeable improvement in Sharpe ratios or decrease in drawdowns from adding them to the portfolio.

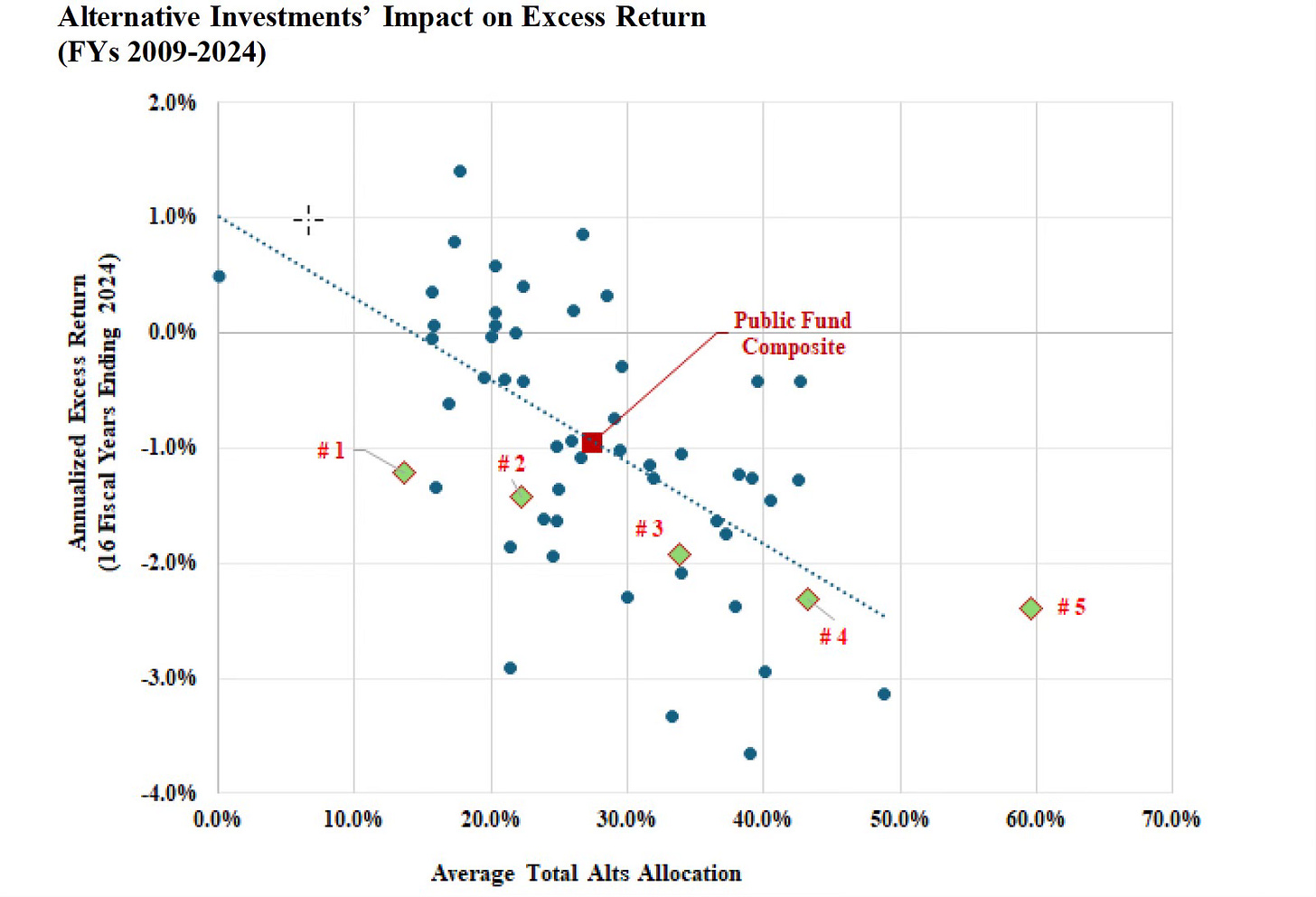

Richard Ennis, a long-time critic of alternative investing, has a series of papers that question the benefits to funds from adding them to the mix.

In the Ennis sample, the excess returns become more negative as the allocation to alternative investments is increased, undercutting a key sales pitch for the allocation. While alternative investing advocates will take issue with the Ennis findings, on empirical and statistical bases, even long-term beneficiaries from alternative investing seem to have become more skeptical about its benefits over time. In a 2018 paper, Fragkiskos, Ryan and Markov noted that among Ivy League endowments, properly adjusting for risk causes any benefits in terms of Sharpe ratios, from adding alternative investments to the mix, to disappear. In perhaps the most telling sign that the bloom is off the alternative investing rose, Yale's endowment announced its intent to sell of billions of dollars of private equity holdings in June 2025, after years of under performance on its holdings in that investment class.

Correlations: Real and Perceived

At the start of this post, I noted that a key sales pitch for alternative investments is their low correlation with stock/bond markets, and to the extent that this historical correlations seem to back this pitch, it may be surprising that the actual results don't measure up to what is promised. There are two reasons why these historical correlations may be understated for most private investment classes:

Pricing lags; Unlike publicly traded equities and bonds, where there are observable market prices from current transactions, most private assets are not liquid and the pricing is based upon appraisals. In theory, these appraisers are supposed to mark-to-market, but in practice, the pricing that they attach to private assets lag market changes. Thus, when markets are going up or down quickly, private equity and venture capital can look like they are going up or down less than public equity markets, but that is because of the lagged prices.

Market crises: While correlations between investment classes are often based upon long periods, and across up and down markets, the truth is that investors care most about risk (and correlations) during market crises, and many investment classes that exhibit low correlation during sideways or stable markets can have lose that feature and move in lock step with public markets during crisis. That was the case during the banking crisis in the last quarter of 2008 and during the COVID meltdown in the first quarter of 2020, when funds with large private investment allocations felt the same drawdown and pain as funds without that exposure.

In my view, this understatement of correlation is most acute in private equity and venture capital, which are after all equity investments in businesses, albeit private, instead of public. It is less likely to be the case for truly differentiated investment classes, such as gold, collectibles and real estate, but even here, correlations with public markets have risen, as they have become more widely held by funds. With hedge funds, it is possible to construct strategies that should have lower correlation with public markets, but some of these strategies can have catastrophic breakdowns (with the potential for wipeout) during market crises.

Illiquidity and Opacity (lack of transparency)

Even the strongest advocates for alternative investments accept that they are less liquid than public market investments, but argue that for investors with long time horizons and clearly defined cash flow needs (like pension and endowment funds), that illiquidity should not be a deal breaker. The problem with this argument is that much as investors like to believe that they control their time horizons and cash needs, they do not, and find their need for liquidity rising during acute market crises or panics. The other problem with illiquidity is that it manifests in transactions costs, manifesting both in terms of bid-ask spreads and in price impact that drains from returns.

The other aspect of the private investment market that is mentioned but then glossed over is that many of its vehicles tend to be opaque in terms of governance structure and reporting. Investors, including many large institutional players, that invest in hedge funds, private equity and venture capital are often on the outside looking in, as deals get structured and gains get apportioned. Again, that absence of transparency may be ignored in good times, but could make bad times worse.

Disappearing Alphas

When alternative investing first became accessible to institutional investors, the presumption was that market-beating opportunities abounded in private markets, and that hedge fund, private equity and venture capital managers brought superior abilities to the investment game. That may have been true then, but that perception has faded for many reasons. First, as the number of funds and money under management in these investment vehicles has increased, the capacity to make easy money has also faded, and in my view, the average venture capital, private equity or hedge fund manager is now no better or worse than the average mutual fund manager. Second, the investment game has also become more difficult to win, as the investment world has become flatter, with many of the advantages that fund managers used to extract excess returns dissipating over time. Third, the entry of passive investment vehicles like exchange traded funds (ETFS) that can spot and replicate active investors who are beating the market has meant that excess returns, even if present, do not last for long.

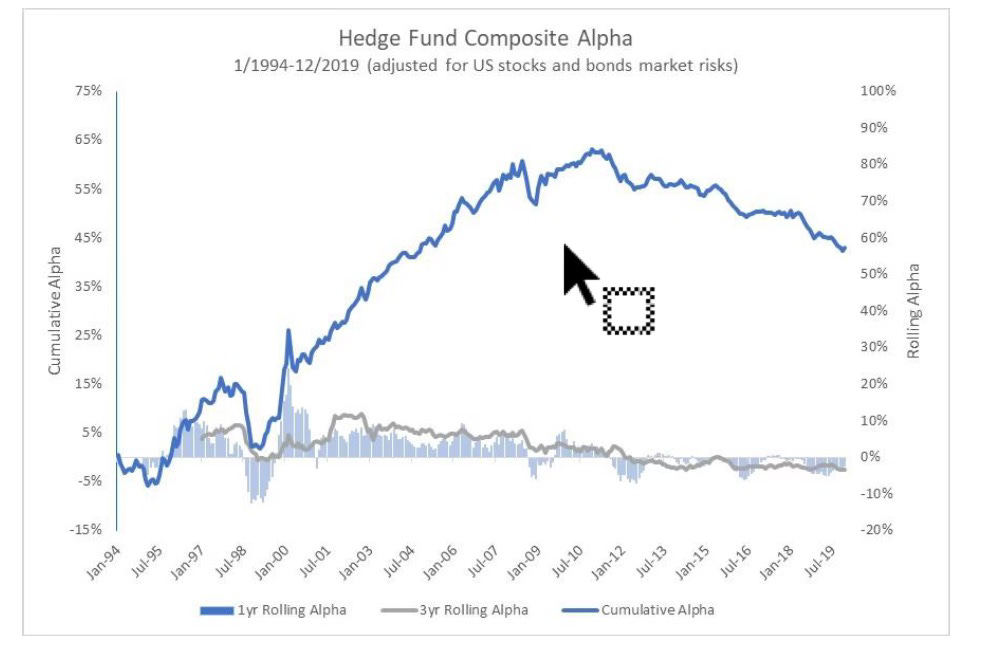

With hedge funds, the fading of excess returns over time has been chronicled. Sullivan looked at hedge funds between 1994 and 2019 and noted that even by 2009, the alpha had dropped to zero or below:

Sullivan, Hedge fund alpha: Cycle or Sunset

In a companion paper, Sullivan also noted another phenomenon undercutting the benefits of adding hedge funds to a public market portfolio, which is that correlations between hedge fund returns and public market returns have risen over time from 0.65 in the 1990s to 0.87 in the last decade.

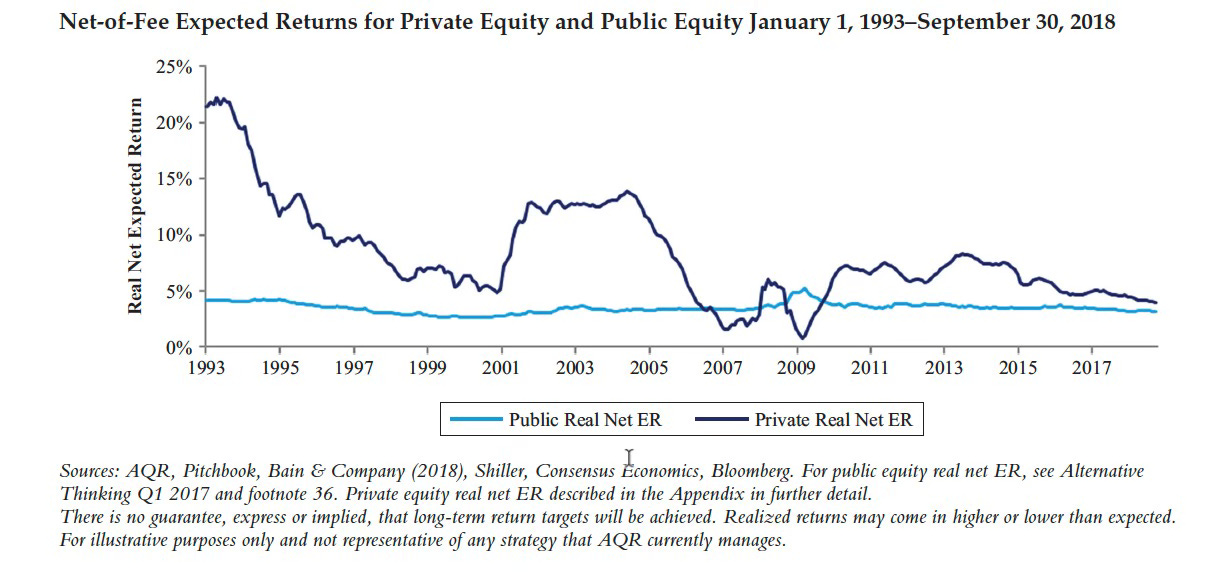

With private investment funds, the results are similar, when performance is compared over time. A paper looking at private equity returns over time concluded that private equity returns, which ran well above public market returns between 1998 and 2007, have started to resemble public market returns in most recent years.

The positive notes in both hedge funds and private equity, as we noted in an earlier section on venture capital, is that while the typical manager in each group has converged to the average, the best managers in these groups have shown more staying power than in public markets. Put simple, the hope is that you can invest your money with these superior managers, and ride their success to earn more than you would have earned elsewhere, but there is a catch even with that scenario, which we will explore next.

The Cost Effect

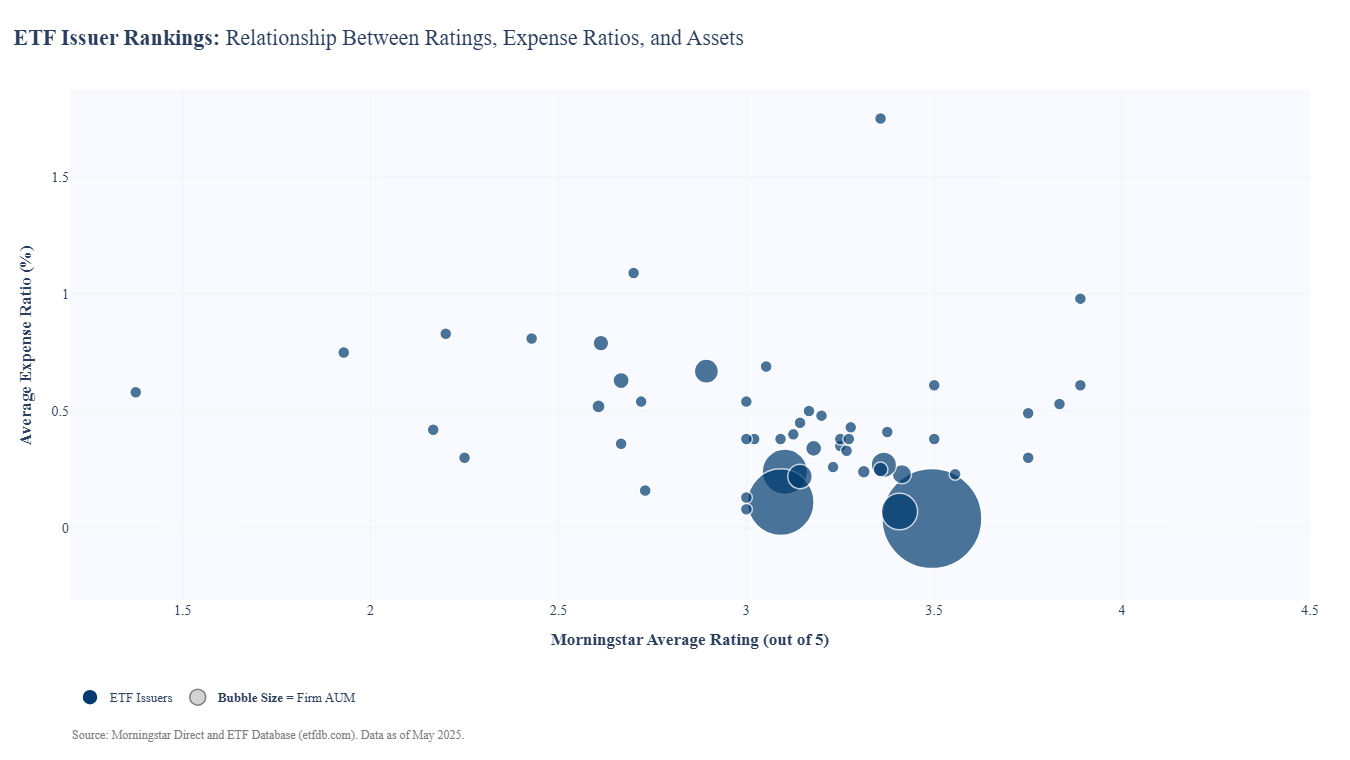

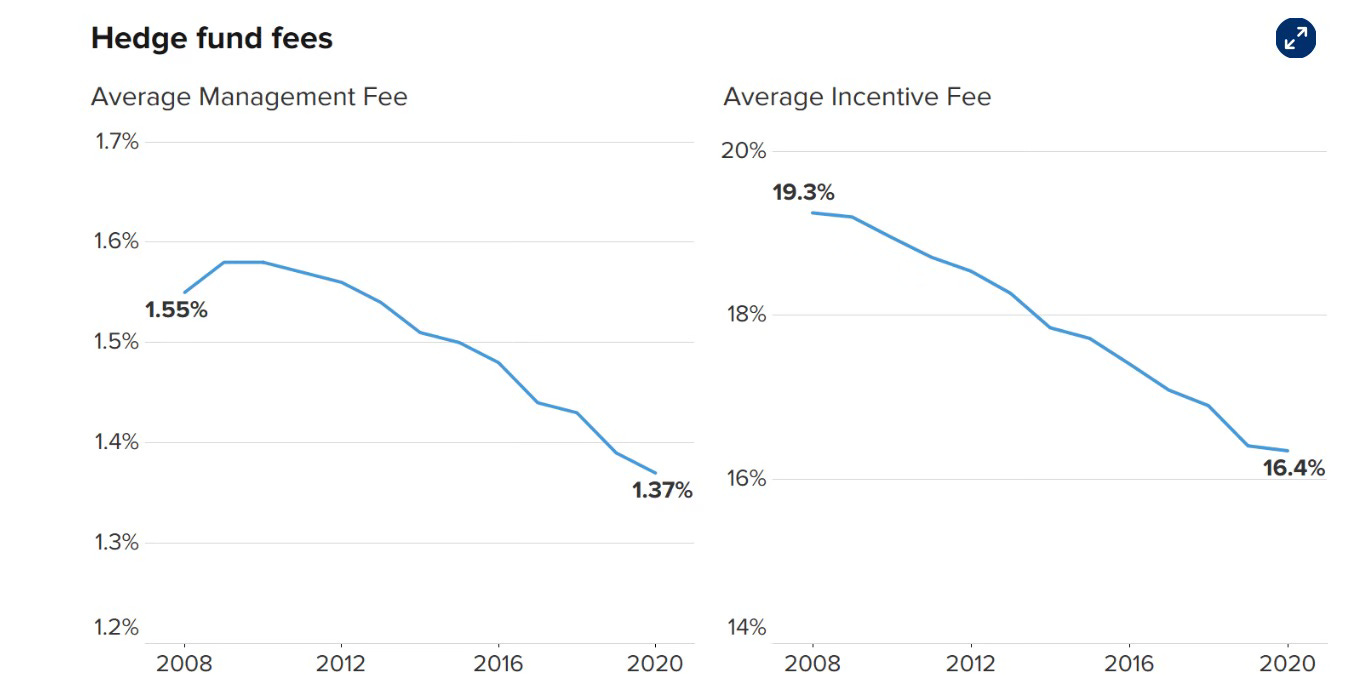

Let's assume that even with fading alphas and higher correlations with public markets, some hedge funds and private market investors still provide benefits to funds invested primarily in public markets. Those benefits, though, still come with significant costs, since the managers of these alternative investment vehicles charge far more for their services than their equivalents in public markets. In general, the fees for alternative investments are composed of a management fee, specified as a percent of assets under management, and a performance fee, where the alternative investment manager gets a percent of returns earned over and above a specified benchmark. In the two-and-twenty model that many hedge and PE fund models used to adhere to, the fund managers collect 2% of the assets under management and 20% of returns in excess of the benchmark. Both numbers have been under downward pressure in recent years, as alternative investing has spread:

Even with the decline, though, these costs represent a significant drag on performance, and the chances of gaining a net benefit from adding an alternative investing class to a fund drop towards zero very quickly.

An Epitaph for Alternative Investing?

It is clear, looking at the trend lines, that the days of easy money for those selling alternative investments as well as those buying these investments have wound down. Even savvy institutional investors, who have been long-term believers in the benefits of alternative investing, are questioning whether private equity, hedge funds and venture capital have become too big and are too costly to be value-adding. As institutional investors become less willing to jump into the alternative investing fray, it looks like individual investors are now being targeted for the alternative investing sales pitch, and as with all things investing, I would suggest that buyer beware, and that investors, institutions and individual, keep the following in mind, when listening to alternative investing pitches:

Be picky about alternatives: Given that the alpha pitch (that hedge fund and private equity managers deliver excess returns) has lost its heft, it is correlations that should guide investor choices on alternative investments. That will reduce the attractiveness of private equity and venture capital, as investment vehicles, and increase the draw of some hedge funds, gold and many collectibles. As for cryptos, the jury is still out, since bitcoin, the highest profile component, has behaved more like risky equity, rising and falling with the market, than a traditional collectible.

Avoid high-cost and exotic vehicles: Investing is a tough enough game to win, without costs, and adding high cost vehicles makes it even more difficult. At the risk of drawing the ire of some, I would argue that any endowment or pension fund managers who pay two-and-twenty to a hedge fund, no matter how great its track record, first needs their heads examined and then summarily fired. On a related noted, alternative investments that are based upon strategies that are so complex that neither the seller nor buyer has an intuitive sense of what exactly they are trying to do should be avoided.

Be realistic about time horizon and liquidity needs: As noted many times through this post, alternative investing, no matter how well structured and practiced, will come with less liquidity and transparency than public investing, making it a better choice for investors with longer time horizons and well-specified cash needs. On this front, individual investors need to be honest with themselves about how susceptible they are to panic attacks and peer-group pressure, and institutional investors have to recognize that their time horizons are determined by their clients, and not by their own preferences.

Be wary of correlation matrices and historical alphas: The alternative investing sales pitch is juiced by correlation matrices (indicating that the alternative investing vehicle in question does not move with public markets) and historic alphas (showing that vehicle delivering market beating risk/return tradeoffs and Sharpe ratios). If there is one takeaway from this post, I hope that it is that historical correlations, especially when you have non-traded investments at play, are untrustworthy and that alphas fade over time, and more so when the vehicles that delivered them are sold relentlessly.

YouTube video