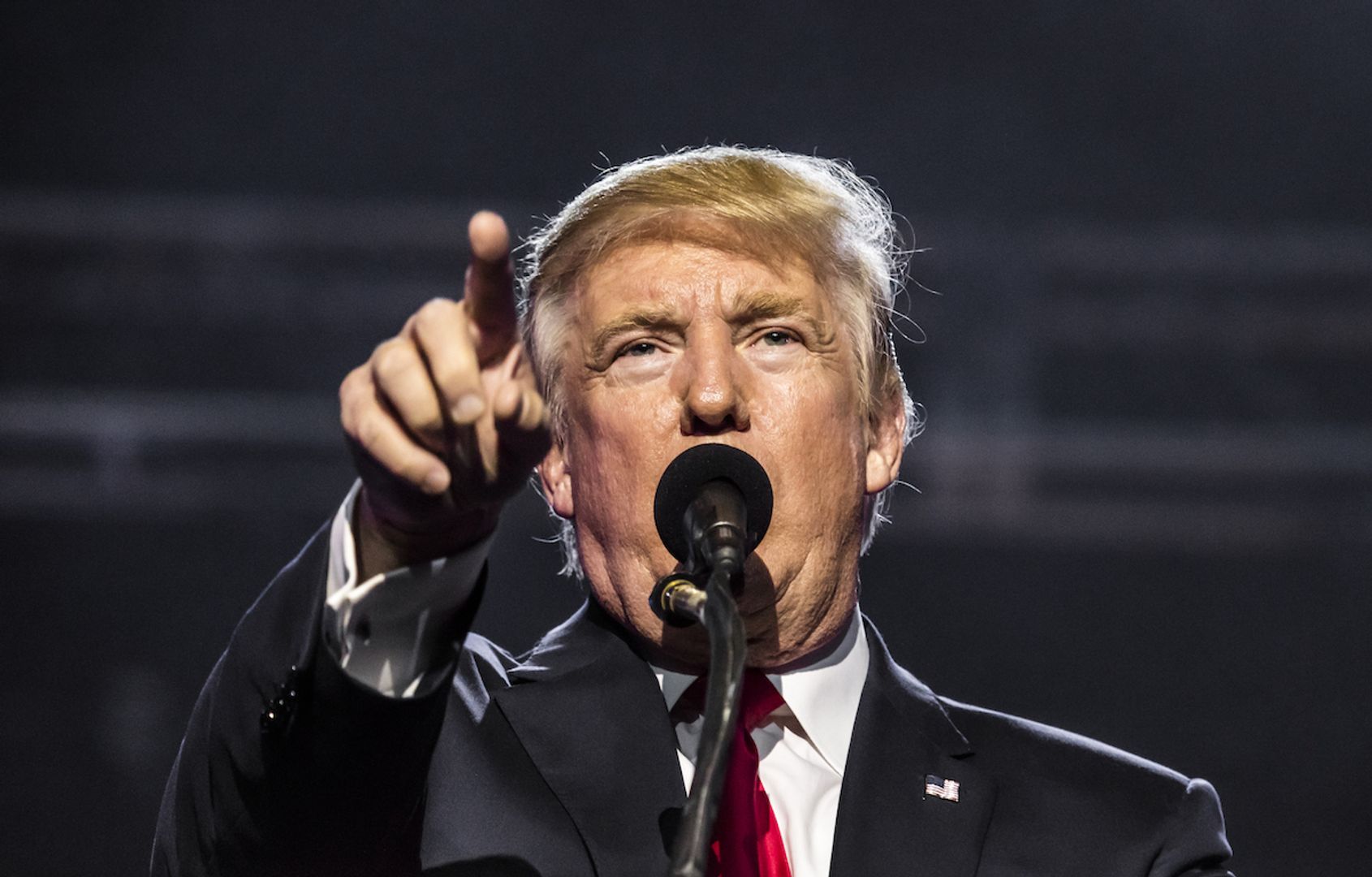

A Trump-induced interest rate cut won’t actually lower mortgage rates

“The president putting this pressure on the Fed would not actually achieve his goal, if his goal is lower mortgage rates,” said Chen Zhao, Redfin economics head.

- A pressured interest rate cut won’t actually lower mortgage rates. It could do the opposite, an economist said. If there is doubt about the central bank’s independence—whether it is politically neutral and committed to its dual mandate of stable prices and maximum employment—it could result in more chaos in the bond market. That would likely push rates on 10-year Treasuries up, and send mortgage rates soaring.

Stock prices spiraled once President Donald Trump unveiled his sweeping tariff regime on so-called “Liberation Day.” But it appeared a bond sell-off caught his attention (although he denies it), and he put some tariffs on ice. That sell-off sent longer-term yields soaring, and as Fortune’s Shawn Tully wrote, Trump “is obsessed with rates on 10-year Treasury bonds” because it influences mortgage rates—and he promised to make America affordable again.

The president has called on the central bank again and again to slash interest rates, but a White House-induced rate cut could do one thing he probably doesn’t want: push mortgage rates up.

“The president putting this pressure on the Fed would not actually achieve his goal, if his goal is lower mortgage rates,” Redfin economics research head Chen Zhao told Fortune. The White House didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

On April 21, Trump posted on social media telling the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates to stop a slowdown since inflation was no longer an issue to him. He called Fed chair Jerome Powell “Mr. Too Late” and “a major loser.” Days earlier, Trump posted that Powell’s termination could not come fast enough, but has since changed his tune. Still, Trump wants lower interest rates. The same moment he said he doesn’t intend to fire Powell, he said: “This is a perfect time to lower interest rates.”

But an interest-rate cut isn’t really the answer for lower mortgage rates, and a pressured cut could make things worse. It should come as no surprise that higher mortgage rates wouldn’t be good for a housing world that is currently at a standstill. Home sales aren’t far off from levels seen in the wake of the Great Financial Crisis because not many people are buying or selling. Would-be buyers can’t afford to because home prices and high mortgage rates are already so high, and would-be sellers aren’t letting go because they don’t want to lose their much lower mortgage rate.

The federal funds rate isn’t directly connected to mortgage rates. It’s the 10-year Treasury mortgage rates pair with, and the spread between the two is higher than usual because of tariff volatility that’s resulted in recession calls, inflation fears, and slowdown anxiety. The Fed is in wait-and-see mode because tariffs could induce inflation and slow consumer spending and business investment. Still, Trump’s comments concerning the Fed and its chair have prompted discussions about the relationship between the White House and central bank.

“If we think that there’s a threat to Fed independence, that’s sort of another point in the camp of more chaos, less faith in the U.S.,” Zhao said, and that could push rates on 10-year Treasuries up, and mortgage rates would increase.

“There’s this notion out there that you can force the Fed to cut, and then if they cut, that means that mortgage rates have to mechanically come down, but that’s just not what happens,” she later said. “Because the Fed only controls that one Fed funds rate. Everything else is determined by markets.”

If the central bank is forced to cut, investors—and therefore markets—won’t see the Fed as politically neutral. The lack of confidence in the Fed and its commitment to its dual mandate to pursue stable prices and maximum employment, could once again trigger a sell-off in the bond market and send yields surging. Plus, investors may anticipate a worsening economy, particularly one marked by stagflation, a nasty mix of high inflation and stagnant growth. That would push long-term interest rates higher, too, because so much of where long-term rates are set has to do with what the bond market is pricing in.

Before the Fed cut its key interest rate for the first time in September 2024 after reining in pandemic-era inflation, mortgage rates were falling. They plummeted out of anticipation of a rate cut, more so than the cut itself. Something similar happened before the president’s election victory, too: The anticipation of a Trump win sent mortgage rates soaring because people were betting a second term would come with hotter inflation.

In a research note post-cut, a Fannie Mae senior economic analyst wrote that the federal funds rate is the interest rate at which banks lend money to one another overnight: a short-term interest rate. Mortgage rates, on the other hand, are long-term rates that are determined in the bond market. The 30-year mortgage rate is benchmarked to the rate of the 10-year Treasury note, set by investors' expectations, the analyst said, so when the rate on the 10-year Treasury note moves, mortgage rates follow suit. In a separate note, a Richmond Fed senior economist wrote the spread between the 10-year Treasury and mortgage rates tends to increase sharply in times of economic stress.

If the Fed were to slash interest rates next month at its next meeting (after Powell warned the Trump tariff agenda could usher in an era of stagflation and maintained a cautious approach to monetary policy) it could send a message to bond investors.

“The markets might say, well, at some point in the future, it will get so bad…the patient will get so sick that we have to apply even more medicine,” Zhao explained. “If that happens, that means we have to really take rates up a lot more than we otherwise would have.”

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com