A record number of Americans are only making their minimum credit card payment

Consumer sentiment has fallen more over the last three months than during the 2008 financial crisis.

- Over 11% of Americans with accounts at the country’s largest banks only made the minimum payment on their credit card bill in the fourth quarter of 2024, a record since the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia began tracking the number 12 years ago. Lower-income consumers have been under increasing pressure since inflation surged to four-decade highs following the pandemic, and price hikes from tariffs will further strain budgets.

Credit-card data shows consumers are under increasing pressure, just as President Donald Trump’s tariffs are poised to significantly raise costs on everyday consumers. Over 11% of Americans with accounts at the country’s largest banks only made the minimum payment on their credit-card bills in the fourth quarter of 2024, a record since the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia began tracking the number 12 years ago.

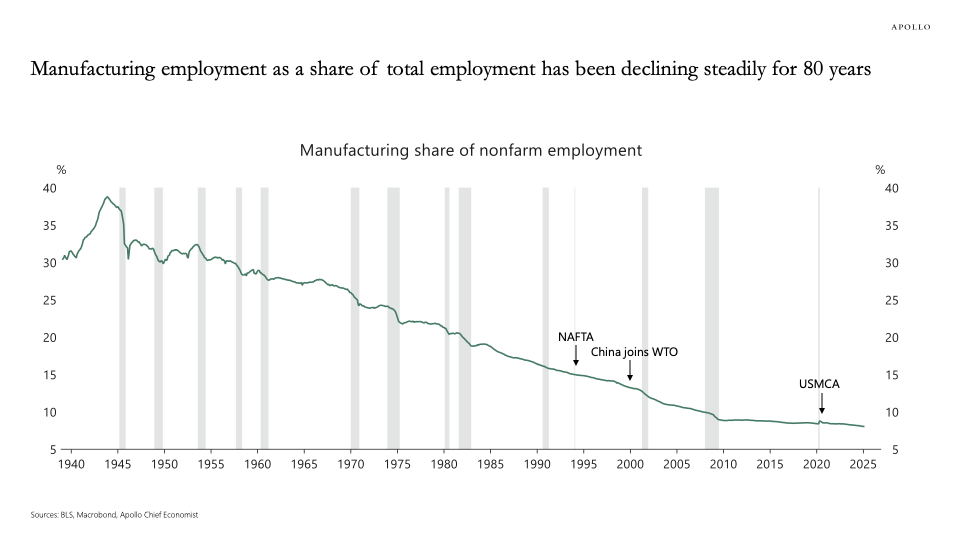

The Philly Fed’s data, published earlier this month, was highlighted over the weekend by Torsten Sløk, chief economist at private-equity giant Apollo. A report from the firm coauthored by Sløk said trade disruptions, particularly between the U.S. and China, could cause a full-on recession by the summer. A growing number of consumers are already vulnerable as delinquency rates rise: The share of credit-card accounts 90 days past due also set a record.

“Collectively, these trends, along with a new series high for revolving card balances, indicate greater consumer stress,” Philly Fed analysts Jeremy Cohn and Brandon Goldstein wrote.

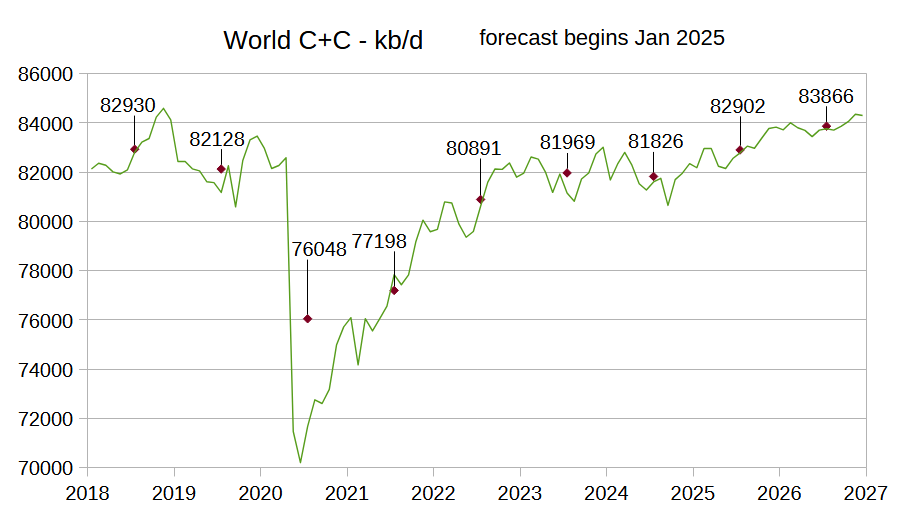

View this interactive chart on Fortune.com

Jay Hatfield, the CEO of Infrastructure Capital Advisors, believes a downturn is imminent if the Fed does not cut interest rates. Along with boosting overall economic activity, that would also make it easier for people to pay off their credit-card debt.

“So you're seeing kind of the normal rotation,” he told Fortune. “Investment spending drops. Labor market weakens up. Consumers spend less.”

Still, people likely won’t cut back astronomically, he said, even in a recession. After all, if more Americans are struggling to pay off their entire balance, it means they are still buying.

“Usually what we say is that consumers consume just like woodchucks chuck wood,” said Hatfield, who manages ETFs and a series of hedge funds.

“What we mean by that is that they’re extremely resilient,” he added. “The low end has to spend money, and the high end wants to spend money and can spend money.”

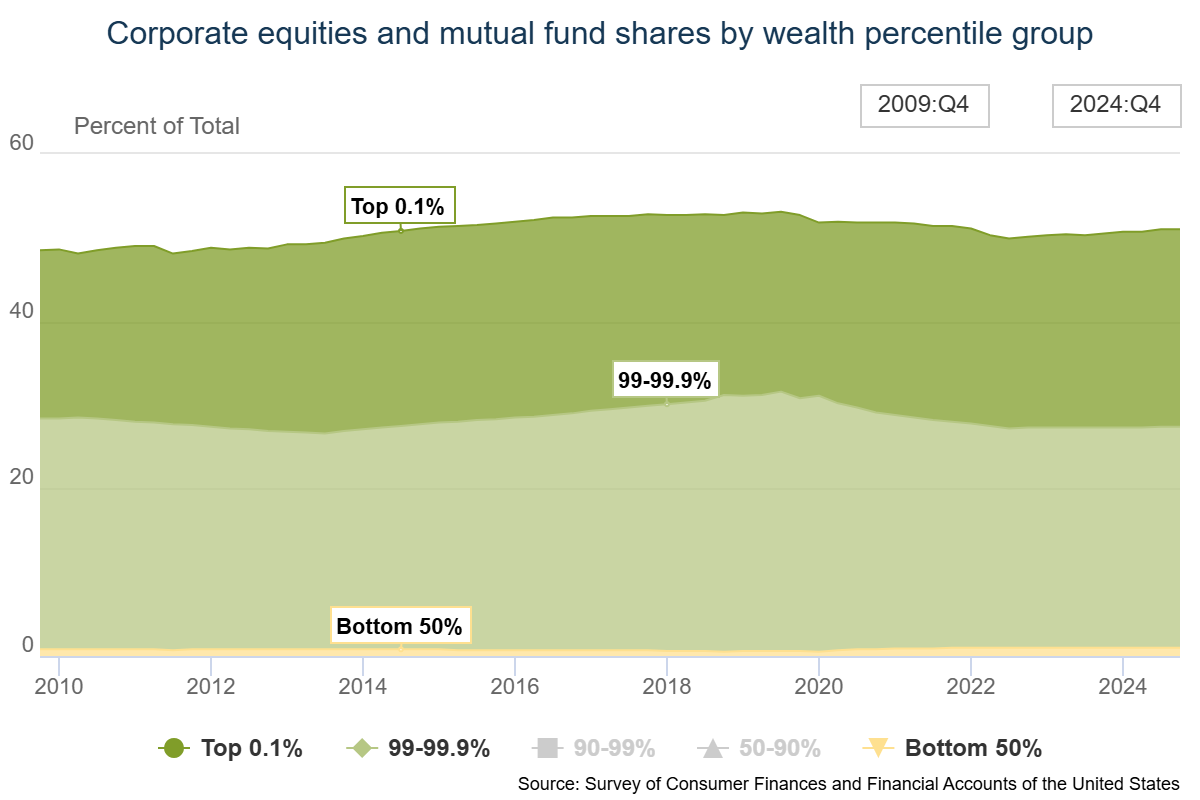

To be sure, seasonal changes are part of the story: Credit-card debt levels always rise amid holiday shopping. The data does emphasize, however, how economic developments over the last half decade have impacted high earners and lower-income individuals much differently.

One example is credit access. The Philly Fed found firms gave the 90th percentile of borrowers their third-largest boost to card limits over the last 12 years. For the 50th percentile, however, card limits stayed level at an average of $5,000, a contraction in real terms due to inflation. A similar trend has played out with mortgages, with the 90th percentile of loans on bank balance sheets growing twice as fast as the median since the final quarter of 2019.

For wealthy people, Hatfield said, post-pandemic inflation boosted home values and was easily outpaced by investment gains from a booming stock market. Lower-income consumers, however, have been forced to weather a significant increase in the cost of living as interest rates remain elevated.

“A huge part of society, they didn't benefit from that inflation,” Hatfield said. “They got hammered by it.”

Tariff worries hang over consumers

Discontent over this situation has been widely credited for helping Trump land a second stint in the Oval Office. His fixation on using tariffs to reorient global trade and raise a growing share of America’s revenues, however, may ultimately not sit well with people most exposed to higher prices.

The Yale Budget Lab estimates Trump’s announced tariffs, as of April 15, will cost the average household $4,900 in last year’s dollars. Tariffs are a type of “regressive tax,” which take a bigger chunk out of the budget from poorer households than from wealthier consumers who pay the same rate.

“It is going to put further pressure on low-income consumers, put the U.S. economy further at risk, and could eventually lead to a recession,” Hatfield said.

On Sunday, Trump suggested tariff income could replace income taxes on households making less than $200,000 a year. Economists and tax-policy experts, including at the center-right Tax Foundation, have said that would be impossible.

The White House did not respond to Fortune’s request for comment.

The chaotic rollout of tariffs has caused consumer sentiment to drop by more in three months than at any point since 1990, including the 2008 financial crisis. Year-end inflation expectations, meanwhile, came in highest since 1981, when price increases were just beginning to retreat after a ruinous spike.

Executives from the likes of Southwest Airlines, Chipotle, and PepsiCo, meanwhile, have warned their businesses are already feeling the effects of people cutting back. After all, a growing number of consumers are struggling to pay off their credit-card bills.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com