Warburg’s CEO says PE firm has thrived for over 50 years by sticking to basics—and not to expect an IPO anytime soon

Warburg keeps a low profile but is one of the most venerable names in PE. Where does it go next?

Warburg Pincus, which claims to be the nation’s oldest private equity firm, is facing the future the same way it handled the past—by sticking to its roots. That’s the case even as a new team of young guns take the reins, including 41-year old Jeff Perlman, who became Warburg’s CEO last July. In an interview with Fortune, Perlman said the nearly 60-year-old Warburg doesn’t expect to change into a lender or list its shares or evolve into an alternative asset manager.

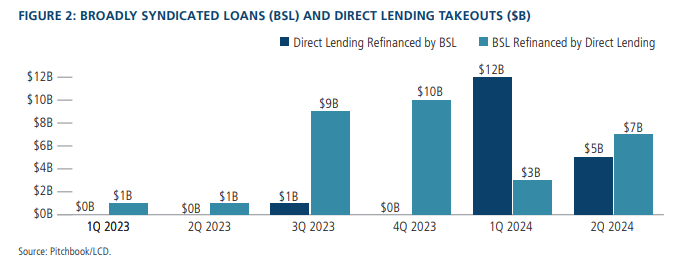

Perlman also made clear Warburg won't be joining the private equity industry's rush into private credit, which has emerged as the hottest area of investing on Wall Street. While Warburg currently has a $4 billion capital solutions founders fund that it raised last year, the pool provides financing to companies but is not a direct lending private capital fund.

“To be clear, we are most focused on remaining an investor first private partnership,” Perlman told Fortune, explaining that Warburg will continue to invest in adjacent sectors like real estate in Asia or GP-led secondaries.

All of this has meant that Warburg cuts a decidedly unflashy figure compared to some of its Wall Street rivals. But for Perlman and his team, that suits the firm just fine. Warburg has returned $151 billion to its investors since 1971 and carried this out with a conspicuous lack of drama.

Youth movement at Warburg

Wall Street is littered with tales of bitter succession and, in private equity especially, the process of passing the torch has led to some messy breakups. Leon Black spent 31 years as CEO of Apollo Global Management but left the firm in 2021 after his ties to Jeffrey Epstein became public. This led to a power struggle at Apollo over who would replace him, Fortune reported, with the role ultimately going to Marc Rowan. Carlyle Group CEO Kewsong Lee abruptly quit in 2022, leaving Carlyle to search for its next leader. (The firm ultimately chose ex-Goldman Sachs exec Harvey Schwartz.) By contrast, Warburg, known for its low-key style, has managed to change its leadership twice without a murmur of dissent coming from its partnership.

Perlman became CEO in July when Chip Kaye, who had led Warburg for more than 20 years, stepped back and became chairman alongside Timothy Geithner, the 75th Secretary of the U.S. Department of the Treasury. Kaye is credited with leading Warburg into Asia in 1994, making it one of the first private equity firms to have a presence there. Perlman, who spent 13 years in Asia, helped expand Warburg’s presence in the continent, which included opening the firm’s Singapore office in 2016.

Perlman, who is young for a private equity CEO, said his ascendence came as part of a broader push by Warburg to elevate the next generation of leaders. The group includes Vishal Mahadevia and Dan Zilberman, Warburg’s global co-head of financial solutions. Mahadevia also leads Asia private equity for the firm while Zilberman is global head of capital solutions. To help ensure continuity, Mark Colodny and Jim Neary, the co-heads of U.S. private equity, are remaining at Warburg. (Colodny is also a former Fortune reporter.)

Nearly everyone in this group—roughly 10 executives who are nearly all men—joined Warburg around the same time in the early to mid-2000s. All the Warburg leaders are “excited about the next phase and the evolution of the firm,” Perlman said.

Kaye, who spent more than two decades as Warburg’s CEO, said handing over the keys to Perlman was “very brand affirming and seamless.” He said the new cohort of Warburg leaders deserved “the same opportunity I had to go see what they could do.”

Small but influential

Warburg's new leaders are taking charge of a firm that has changed dramatically since its founding in 1966. That’s the year that Lionel Pincus and Eric Warburg launched the firm that bears their name, and that has had an outsized influence on the evolution of the private equity industry. Warburg launched its first PE fund in 1971 with a $41 million pool of capital—a sum it called in on day one. This is much different from current PE practices, where firms take commitments and call in capital when they need the money. “In those days, nobody trusted their investors,” Perlman said.

In the 1970s, it was Pincus who led efforts to change regulations so as to allow state pension funds to invest in private equity funds, which spurred the growth of the emerging PE industry. In Warburg’s case, it allowed the firm to raise a then-record $1.2 billion fund in 1987, backed by investors that included pension funds of AT&T and General Motors.

“We're still today the only investor that has more than 50 years of a continuous investing track record,” Perlman said.

While Warburg has worked to stay true to its roots, the firm has gotten bigger. Known for its investments in the fields of technology, healthcare, financial services and industrials. Warburg currently has about 800 employees, including more than 275 investment professionals, that are spread across offices including New York, Berlin, London, Singapore and Shanghai. It has over $87 billion in assets under management and has invested more than $120 billion in over 1,000 companies.

Warburg has a growth-oriented mindset that allows it to invest in all sorts of deals, including early-stage as well as growth. The firm does take part in buyout transactions, which it calls “growth buyout,” while using debt selectively. One of its most well-known deals was CrowdStrike, the cybersecurity firm. In 2011, Warburg was CrowdStrike’s first investor and remained its largest shareholder until its $612 million IPO in June of 2019. Warburg is a steady performer, providing consistent returns, Perlman said. “We've never had to go to our investors and ask for a mulligan, right?” he joked.

A changing perception

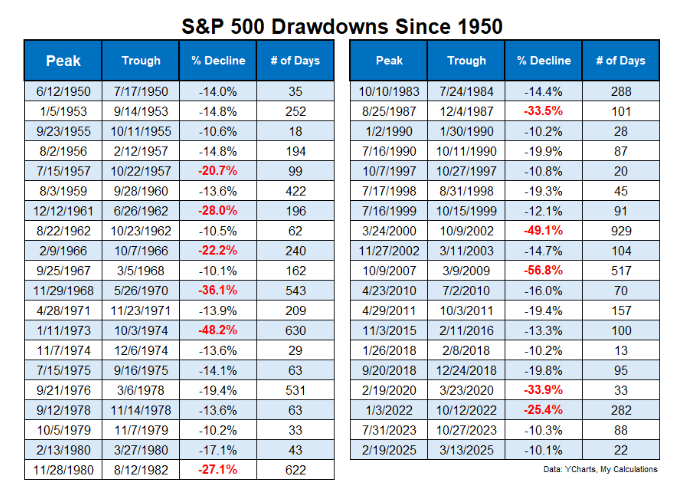

Today, Warburg stands as a venerable private equity firm that has weathered several economic cycles, like the global financial crisis of 2007, which put the PE industry on its heels for several years, and the covid-19 pandemic that led some firms to suspend investments for some months. The end of covid, in 2021, spurred several firms to return to dealmaking, resulting in a record number of mergers that year that were often clinched at high multiples.

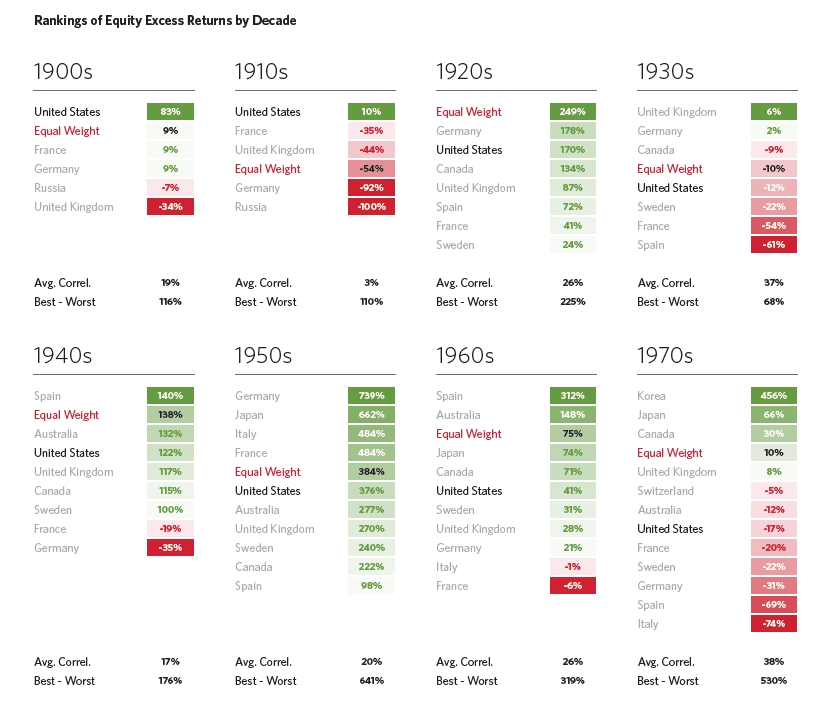

The PE industry is still dealing with the aftermath of the 2021 bubble, with many firms unable to exit their deals because of the slowdown in IPOs and M&A. This has made returns harder to come by and caused PE IRRs to come under pressure. Buyout funds have generally outperformed public markets, but returns for 10-year pools have fallen by three percentage points in North America over the past three years, according to Bain’s Global Private Equity Report 2025.

Warburg has not been immune to the headwinds of the last few years. Since its founding, the firm has raised about 25 funds in all, including Warburg Pincus Global Growth 14, the firm’s flagship fund, which raised $17.3 billion in 2023, its biggest ever. This was up 15% from its prior fund, Global Growth (technically Warburg’s 13th flagship pool), which collected $15 billion in 2018. Fund 13 is generating a net IRR of 15% while Global Growth 14 produced a net IRR of 20% as of the end of 2024, according to a person familiar with the situation.

In private equity, a good IRR typically exceeds 20%. Global Growth 14 is considered too young to critique but the other pool, fund 13, is falling short. Warburg declined to comment on the performance of the funds.

Still, unlike many of its competitors, Warburg has been exiting. So far this year, the PE firm has sold three companies in three different sectors. Clearlake Capital earlier in March bought Warburg’s stake in ModMed in a deal that valued the healthcare tech SaaS company at $5.3 billion. Warburg also agreed to sell heat pump maker Sundyne to Honeywell for $2.16 billion. And, in February, Warburg completed the sale of its stake in broker dealer Kestra to Stone Point Capital.

No IPO right now

Warburg has also evolved since its founding and, while it plans to stick to private equity investing, it also expects to focus on capital solutions, real estate in Asia and GP-led secondaries.

Another area of growth may come from the Middle East where Warburg already has a presence. The firm is partnering with Hassana Investment Company to invest in Saudi Arabia. Hassana is the investment manager of General Organization Social Insurance, or GOSI, one of the world’s largest pension funds with about $320 billion AUM. Warburg has tapped senior partner, Viraj Sawhney, to lead investing activities in the Middle East.

Like many, Warburg recognizes the importance of AI and has been betting on companies using the technology, including Personetics, CData Software, and Contabilizei. But the PE firm has no interest in “trying to predict who's going to end up as having the most efficient ChatGPT equivalent,” Perlman said. As a firm, Warburg also uses AI, building agents to help it determine when companies might come to market or helping to find businesses that fit their investment criteria.

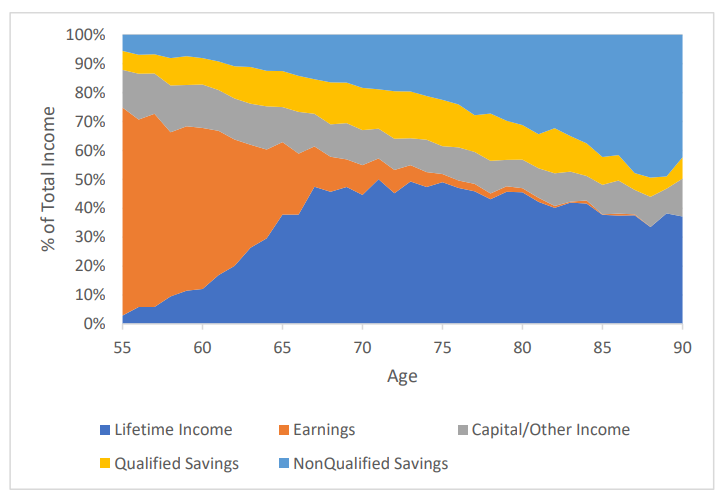

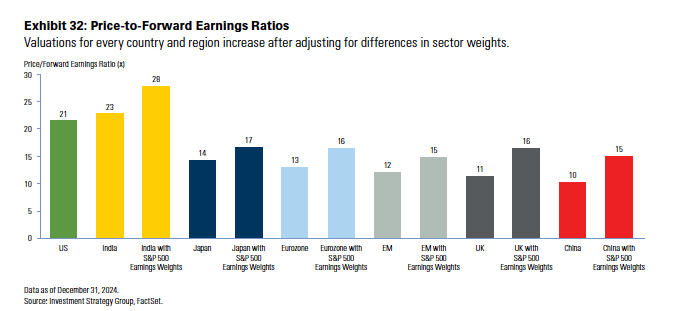

Over the course of its long history, Warburg has had to navigate shifting perceptions of private equity. Some PE executives have complained that the sector is misunderstood and unfairly villainized. Perlman notes that when he joined Warburg in 2006, people did not understand what private equity was, but as the industry has grown, the firm’s investments have touched many people. This coincides with a rise in the stock market. And, as more players are investing in the stock market, and with seven tech stocks currently comprising roughly 30% of the S&P 500, some investors are seeking out alternatives as a way to diversify.

Now, when Perlman meets a non-finance person, they might not know the Warburg name. But then he mentions some of the well-known businesses that Warburg has invested in including eye care company Bausch & Lomb, retailer Neiman Marcus and CityMD. “Immediately it resonates. They understand who [Warburg] is on that front,” he said.

When it comes to an IPO, that’s also off the menu for Warburg. Many of Warburg’s rivals, including Blackstone, Carlyle Group, KKR, Ares, EQT, CVC and TPG, have gone public. Don’t expect Warburg to join the trend right now. “If we felt we are at a competitive disadvantage by not being public, we would need to revisit. I think the opposite is true today – I believe it’s a real distinct competitive advantage for us to remain an investor first private partnership,” Perlman said.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com