Transcript: Charley Ellis on Rethinking Investing

The transcript from this week’s, MiB: Charley Ellis on Rethinking Investing, is below. You can stream and download our full conversation, including any podcast extras, on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, and Bloomberg. All of our earlier podcasts on your favorite pod hosts can be found here. ~~~ This is Masters in Business with Barry… Read More The post Transcript: Charley Ellis on Rethinking Investing appeared first on The Big Picture.

The transcript from this week’s, MiB: Charley Ellis on Rethinking Investing, is below.

You can stream and download our full conversation, including any podcast extras, on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, and Bloomberg. All of our earlier podcasts on your favorite pod hosts can be found here.

~~~

This is Masters in Business with Barry Ritholtz on Bloomberg Radio.

Barry Ritholtz: This week on the podcast, I have an extra, extra special guest. Charlie Ellis is just a legend in the world of investing. He started for the Rockefeller Family Office before going to DLJ and eventually ended up launching Greenwich Associates. He’s published 21 books. He’s won every award you can win in the World, world of Finance. He was a member of Vanguard’s board of director. He was chairman of the Yale’s Endowment Investment Committee and his, not only did he write 21 books, his new book, rethinking Investing, is just a delightful snack. It’s only a hundred pages and it distills 60 years of investing women wisdom into a very, very short read. I found the book excellent. And Charlie, as delightful as always, I really enjoyed our conversation and I think you will also, with no further ado, my discussion with Charlie Alice.

Charley Ellis: Thank you, Barry.

Barry Ritholtz: Well, thank you for being here. First of all, we’re gonna talk a lot about the book in a bit, which I really just devoured over a cup of tea. It was that short and very delightful. But before we do that, I want people to fully understand what a fascinating background you’ve had and how really interesting your career is. Where you began and where you ended up. You get a master’s in business from Harvard Business School, a PhD from New York University, and then you sort of happened onto Rockefeller Foundation. How did you get that first job? How did you discover your calling?

Charley Ellis: A friend of mine at business school said, or have you got a job yet? I said, no, not yet. Got a couple of things that I’m working towards. He said, well, I’ve got a friend, and I thought he meant the Rockefeller Foundation actually. He meant the Rockefeller family in their investment office. And very, very bright guy. Came up from New York to Cambridge, Massachusetts, climbed to the third floor of my apartment building, and we did an interview in what I would have to describe as shabby graduate student facility. And at the end of half an hour, I realized it isn’t the foundation that he’s talking about. He’s talking about something else. And I gotta figure out what that is. At the end of the second half an hour, I knew he was talking about investing where there were no courses at that time, at the Harvard Business School on Investment Management.

And he’s really describing the Rockefeller Family Office

Barry Ritholtz: Yes. Not necessarily the foundation. So what were they doing at that time? What were their investments like?

Charley Ellis: Well, they invested the family’s fortune. And at that time, relative to other family fortunes, it was the large major, so on and so on. They were also, because they’d been generous philanthropically for years, managing several charitable organizations, endowments. So the combination made us a consequential investment client for Wall Street as Wall Street was just coming into doing serious research on individual companies and industries. So it was take off time for what became institutional investing.

Barry Ritholtz: So give us some context as to that era. This is the 1970s and eighties, essentially when, when that

Charley Ellis: Was in 1960s,

Barry Ritholtz: So late sixties, not a lot of data available on a regular basis. And modern portfolio theory was kind of just coming around. Is That right?

00:03:52 [Speaker Changed] Oh, it was just a, an academic curiosity. Nobody’s right mind thought it had a chance of being proven. But you know, if you go back to those days, if we came back to it, we would all of us agree with the people who said, no, it’s nothing. It’s not gonna happen. The transformation of the whole investment management world, information availability, legislation, who’s participating? What’s the trading volume? What kind of information is available? How fast can you get it? Wow. Every one of those dimensions has changed and changed and changed. The world is completely different today.

Barry Ritholtz: You detail that in the book. We’ll talk about that in a little bit. That if you just go back 50 years, completely different world, as you mentioned, the volume, but who the players are, how technology allows us to do things that we couldn’t do before. And that we’ve also learned a lot since then.

Charley Ellis: We sure have, you know, it’s hard to remember, but I do because I was new and fresh. And so it made an impression. Trading volume was 3 million shares in New York. Stock Exchange listed. Now it’s six, seven, 8 billion. That’s a huge change. Order of magnitude. The amount of research that was available was virtually zero.

Barry Ritholtz: Now, I recall. Well, the CCH binders used to get updates on a regular basis, the clearinghouse binders, and then it was essentially Zachs and a whole bunch of different companies. But that’s really late eighties, right? Like when did the research explosion really happen?

Charley Ellis: The research explosion happened in the seventies and then into the eighties, but the documents that you were looking at or thinking about, were all looking backwards,

Give you the plain vanilla facts of what’s happened in the last five years in a standardized format with no analytical or insight available. Now everything about research is a future, and it’s full of factual information and careful interpretation. It’s really different.

Barry Ritholtz: That’s really interesting. So how long were you at Rockefeller before you launched Greenwich Associates in 1972?

Charley Ellis: Well, I was there for two and a half years. Then I went to Wall Street with Donaldson Lufkin and Jennrette for six, and then I started Greenwich Associates.

Barry Ritholtz: So what led you after less than a decade to say, I’m gonna hang my own shingle? It seems kind of bold at that point. You’re barely 30 years old.

Charley Ellis: It was a little nervy. I have to graduate. There are a couple of different parts. One is that I knew from my own personal experience, I had no ability to get my clients to tell me what I was doing right or wrong. They’d always say, oh, you’re doing fine. Just keep it up. You’re doing fine. And then I have no idea what my competition was doing. You know, if we could give factual information on exactly how well each firm is doing and how every one of their competitors are doing, we could interpret that in ways that clients would find really useful. And then we could advise them on specific recommendations based on the facts. Really undeniable facts based on 300, 500, 600 interviews with people who made the decisions and it worked

Barry Ritholtz: Well I can’t imagine they’re happy with the outcome because what you eventually end up learning is that a lot of people who charge high fees for supposedly expert stock picking, expert market timing expert allocation, they’re not doing so well. And it turns out, at least on the academic side, it appears that the overall market is beating them.

Charley Ellis: I wouldn’t quite say it that way,

So I wouldn’t deny what you’re saying, but I would’ve say it differently when the purpose of any market, a grocery store, drug store, filling station, the purpose of any market is really to find what’s the right price that people will buy and trade at. And the securities industry is a very strong illustration of that. Lots of buyers, lots of sellers, what do they think is the right price to do a transaction? And they put real money behind it. So that purpose of a market gets better and better and better when the participants are more skillful, when the participants have more information, when the information is really accessible. And that’s what’s happened to the securities markets. The ability to get information from a Bloomberg terminal, if you don’t mind using Mike’s name. Sure. But seriously, Bloomberg Terminal will spew out so much in the way of factual information.

And there are hundreds of thousands of these terminals all over the world, huh? So everybody in his right mind has ’em and uses them. Everybody’s right. Mind has computing power that would knock the socks off. Anybody who came from 1970 got dropped into the current period, that would just be amazed at the computing power. And they don’t use slide rules anymore. You know, back in the early seventies, everybody used a slide rule. Wow. And we were proud of ’em, and we were pretty skilled at it. But it’s nothing like having computing power behind you In those days. There were very few in the way of federal regulations. Now it’s against the law for a company to have a private luncheon with someone who’s in the investment world.

Barry Ritholtz: Right. Reg FD said it has to be disclosed to everybody at once. So it is, you can’t just whisper it…

00:09:45 [Speaker Changed] And everybody gets the same information at the same time. So basically what you’ve got is everybody in the game is competing with everybody knowing everything that everybody else knows at exactly this very same time. And you can be terribly creative and wonderfully bright and very original, but if everybody knows exactly what you know, then they’ve got computing power. So they can do all kinds of analytics. Then they’ve got Bloomberg terminal, so they can do any backgrounding that they wanna find. It’s really hard to see how you’re gonna be able to beat them by much, if anything. And the truth is that people who are actively investing are usually making, they don’t mean to, but they are making mistakes. And those mistakes put them a little bit behind, a little bit behind, a little bit behind the market. And then of course, they charge fees that are high enough. So trying to recover those fees while trading, and you can only trade successfully by beating the other guy when he’s just as good as you are. He’s got just as big a computer as you have. He’s got just the same factual information you have. Then all those other different dimensions. There’s no way that you could think, oh yeah, this is a good opportunity to do. Well, that’s why people increasingly it, in my view, sensibly turned index funds to cut down on the cost. Huh.

Barry Ritholtz: So it’s interesting how well you express that because sometime in the 1970s you start writing your thoughts down and publishing them. Not long after, in 1977 you win a gram and dot award. Tell us what you were writing about back in the 1970s and what were you using for a data series when there really wasn’t a lot of data?

00:11:30 [Speaker Changed] Well, the data did come, but it came later. And fortunately it proved out to be very strong confirmation for what I’ve been thinking. But I was in institutional sales and I would go around from one investor to another, to another, to another, to another. And I knew pretty quickly. They’re all really bright guys. They’re all very competitive, they’re all very well informed. They’re all very serious students trying to get better and better and better. Their job is to beat the other guys. But the other guys are getting better and better and better all the time. Striving to be best informed. They get up early, they study on through the night. They take work home on weekends. Competition, competition, competition, competition. How are you going to do better than those other guys when there’s so much in the way of raw input is the same? And the answer is no. You can’t.

Barry Ritholtz: Michael Maubboisson calls that the paradox of skill, as all the players in a specific area get more and more skillful. Outcomes tend to be determined more by random luck because everybody playing is so good at the game.

00:12:41 [Speaker Changed] Absolutely true.

Barry Ritholtz: So I’m fascinated by this quote. We’ve been talking about errors and making mistakes. One of the things from your book that really resonated is quote, we are surrounded by temptations to be wrong in both investing and in life. Explain,

00:13:00 [Speaker Changed] Well, we all know about life. They were tempted by beautiful men, beautiful women we’re tempted by whiskey, gin, or other drinks where some of us get tempted by drugs and other things like that. So there are lots of temptations out and around that you think about. All of us in the investment world are striving to be rational, which is a terribly difficult thing to do. Warren Buffett is rational and is brilliantly rational. He also does an enormous amount of homework. He also has terrific ability to remember things that he studied and he spends most of his time reading, studying, memorizing and reusing. Very few people have that kind of ability, natural ability that he has. But most of us now have equipment that’ll damn near do the same thing. And you could call up things from the historical record anytime you want to. It puts everybody in a position of being able to compete more and more skillfully all the time.

00:14:10 And therefore, candidly, I think it’s the fees are a big problem. And then the second problem is, yes, we’ve got opportunities to be more and more skillful and more and more effective. But actually what we also have, which really drives anybody who’s serious about examining the data, drives ’em nuts than anybody who is an investor wants to deny it. And that is that we make mistakes. We get scared by the market after it’s gone down. We get excited about the market positively after it’s gone up. And we interpret and make mistakes in our judgment. Now, this wonderful section in this little bitty book that I’ve just finished, wonderful section on behavioral economics, terrific book by Daniel Kahneman, thinking Fast, thinking Slow. That’s several hundred pages. And anybody in the investment world ought to read it because it tells you all about what we need to know about ourselves.

00:15:06 And I’ve got one chapter that just ticks off a whole bunch of things. Like 80% of people think they’re above average dancers. 80% of people think they’re above average drivers. If you ask men a question on are you really above average at various kinds of skills, they get up to pretty 90%, 95% saying they’re very, very, very good. Now, if you look at a college group, are you gonna have happier life than your classmates? Yes, by far. Are you gonna get divorced as much as your classmates? Oh no, that won’t happen to me. Then all kinds of other things that anybody looking at it objectively would say, you know, Barry, that just isn’t the way it’s gonna happen. These guys aren’t that much better drivers than the normal crowd. In fact, they are part of the normal crowd.

00:15:58 [Speaker Changed] You know, we, we all imagine that we’re separate from the crowd. I love the expression, I’m stuck in traffic when the reality is if you are near a major urban center during rush hour on Workday, you’re not stuck in traffic. You are traffic. And we all tend to think of ourselves as separate. Really, really fascinating stuff. I’m fascinated by the evolution of your investing philosophy. You start with Rockefeller Family Office, I assume back in the 1960s that was a fairly active form of investing. Tell us a little bit about how you began, what sort of strategies were you were using and then how you evolved.

00:16:40 [Speaker Changed] Woo. Boy, that’s a complicated question. First of all, in the early sixties when I was working for the Rockefeller family, that was the old world. All kinds of changes have taken place since then and virtually turned every single dimension of what was the right description of the investment world into a very different opposite version. And it change like that makes it almost a waste of time to talk about what was it like. But just for instance, I did some analysis of a company called DuPont Sure. Which was one of the blue chip blue chips of all time. And I had also been studying IBM, which was a wonderful company. And I realized, you know, IBM has got an ability to generate its own growth because it is creating one after another, advancement in computing power. And they’ve got a terrific organization behind it, and they are able to create their own growth.

00:17:43 IBM is a true growth company. DuPont needs to invent something that other people would really want, and it has to be something that’s really new. And then they get patent protection for a certain period of time, and then they lose the patent protection because it’s completed. They’ve got a different situation. Both companies were selling at 30, 32 times earnings. One company I thought was sure to continue growing and the other I wasn’t so sure. So I got permission to go down to Wilmington, Delaware, and for three days I had nothing but one interview after another, after another, after another. Were the senior executive of the DuPont organization. And they were very candid. And they told me about their problems. They told me about their opportunities. They told me about their financial policies. Their first level financial policies were that they would always pay out half their earnings and dividends long established.

00:18:43 And that was the way they did things. And the second thing is, they had a major commitment to nylon, but nylon was no longer patent protected. And so the profit margins of nylon were gonna come down for sure and come down rather rapidly because competition was building up pretty quickly. They hoped to build one terrific business in a leather substitute called Core Fam. But as I talked to the executives, they kept talking to me about, we’re having difficulty getting people to use Core Fam. We’re getting people who make shoes to think about using Core Fam. You know, we can’t get sales outside the United States to really get going. And we’re having a difficult time getting sales inside the United States. And candidly, it doesn’t look like this is gonna turn out to be the bonanza we had all thought it was going to be just a year or so ago.

00:19:35 Well, it doesn’t take a genius and it doesn’t take a very experienced person. And I was not a genius and I was not an experienced person, but I could see the handwriting. Wait a minute, if you only reinvest half your earnings each year and your major business is going to be more and more commoditized and your major new business is not taking off, you got a real problem here and you’re gonna have a tough time keeping up the kind of growth that would justify selling for 30 plus times earnings. Whereas IBM was guaranteed to be virtually guaranteed to be able to do that. ’cause they didn’t have very much the way of competition and they really knew what they were doing and they kept cranking it up. So what do you do? I came back and said, I know that the family, the Rockefeller family has many friends in the DuPont organization, but they also have many friends in the Watson family of IBM. I think it would be a great thing if we would sell off the holdings in DuPont and use the money to buy into IBM go out of one family friends into another, family friends. They would all understand it. And that was what was done. And of course it involved a substantial amount of ownership being shifted. And I’ve always thought to myself, wow. In that one specific recommendation, I earned my keep for several years.

00:21:03 [Speaker Changed] Huh. Really interesting. And and it’s fascinating ’cause that’s what was being done in every institutional investor and every endowment. People were making active choices,

00:21:15 [Speaker Changed] But they also were making lots of mistakes. Right. If you looked at what happened in the two years after my recommendation, IBM doubled and DuPont almost got cut in half.

00:21:26 [Speaker Changed] Wow. So that worked out really well. So it’s kind of fascinating that you’ve evolved into really thinking about indexing. ’cause when you’re, you were chairman of the Yale Endowment Investment Committee, David Swenson was famously the creator of the Yale model, and he had a lot of focus on private investment, on alternatives, on venture capital, hedge funds, as well as commodities. What made that era so different where those investments were so attractive then and apparently less attractive to you today?

00:22:02 [Speaker Changed] First you have to understand that David Swenson was a remarkably talented guy. He was the best PhD student at Jim Tobin Nobel Prize winner ever had. He was the first person to do an interest rate swap, which is the first derivative transaction that took place in this country between IBM and the World Bank. Which just to show you, everybody had told him, you’ll never be able to do that, David. So we’re talking about a very unusual guy.

00:22:33 And he was creative and disciplined in a remarkable combination. And he was the first person of size to get involved in a series of different types of investing. And then he very carefully chose the very best people in each of those different types. One day I was thinking, you know, he’s really done some very creative work. I wonder what’s his average length of relationship. Because the average length of relationship with most institutions was somewhere between two and a half and three and a half years. High turnover of managers, the calculation, it was 14 years on average and they were still running. So it’d probably be something like 20 years of typical relationship or duration, many of these managers when they were just getting started. So it’s the most dicey period in any investment organization. Very, very unusual and creative guy said to me after he’d been doing this for quite a long time, you know, the nature of creativity payoff is getting less and less and less because of everybody else’s doing what I’ve been doing. It’s not as rewarding as it used to be. And because I’ve been choosing managers and other people are trying to get into those same managers, they’re not as differentiated as they used to be. The rate of return magnitude that I’ve been able to accomplish 10 years ago, 15 years ago, I’m not gonna be able to do in 10 or 15 years into the future. And I think he was right.

00:24:10 [Speaker Changed] Huh. Really, really interesting. So how do you end up from going from the Yale Endowment to the Vanguard Board of Directors? Tell us where where that relationship came

00:24:21 [Speaker Changed] Completely different. Each one was doing what they were capable of doing really well. And Vanguard was focused on minimizing cost. And they really systematic at it different orientation. The orientation of the Yale endowment was to find managers and investment opportunities that were so different that you might get a higher rate of return. So attacking to reaching for higher and higher rate of return. Vanguard was reaching for lower and lower cost of executing a plain vanilla proposition. Index funds. Kanes once had somebody say, you’ve, you seem to have changed your mind. He said, yes, I, when the facts change, I do change my judgment. What do you do when the facts change? And the reality is we’ve been looking at a market that has changed and changed and changed and changed and the right way to deal with that market has therefore changed and changed and changed and changed then what you could have done in the early 1960s, you can’t do today. And what you should have done in the early sixties was go find an active manager who could knock the socks off at the competition. But it just, the competition is so damn good today that there isn’t a manager that can knock the socks off.

00:25:41 [Speaker Changed] And a quote from your book is, the grim reality is clear active investing is not able to keep up with, let alone outperform the market index. That’s the biggest change of the past 50 years, is that it’s become pretty obvious that the deck is used to be in favor of active managers. Now it seems to be very much stacked against them

00:26:06 [Speaker Changed] Because they’re so very good. It’s ironic, ironic, ironic.

00:26:10 [Speaker Changed] The paradox of skill. Yep. Huh. Really, really fascinating. You, you referenced some really interesting research in the book. One of the things I find fascinating is that research from Morningstar and DALBAR show that not only do investors tend to underperform the market, they underperform their own investments. Tell us about that.

00:26:36 [Speaker Changed] Because we’re human beings, as any behavioral economist would point out to you, we have certain beliefs and those beliefs tend to be very, very optimistic about our skills. And we think we can help ourself get better results, or at least to minimize the negative experiences. And the reality is that over time just doesn’t work out to be true. The average investor in an average year loses two full percent by making mistakes with the best of intentions, trying to do something really good for themselves. They make mistakes that are costly and that cost. Think about it, if you think the market’s gonna return something like six or 7%, you lose 2%, maybe two and a half, maybe three for inflation, call it two point a half. Whoop. That’s something down. Then you’ve got fees and costs. Gee was you add onto that if you did add on another 2% that you’ve made mistakes, you’re talking about a major transformation to the negative of what could have been your rate of return.

00:27:54 [Speaker Changed] Let’s put some, some numbers, some mean on that bone. You cite a uc Davis study that looked at 66,000 investor accounts from 1991 to 1996 over the that period, the market gained just under 18% a year, 17.9% a year. Investors had underperformed by 6.5% a year. They gave up a third of gains through mistakes, taxes, and costs. And then DALBAR does the same thing. And that’s where the two to 3% in a low return environment is. So how should investors think about this tendency to do worse than what the market does?

00:28:37 [Speaker Changed] Well in, in my view, and it’s part of the rethinking investing concept of the book, is if you find a problem that’s a repetitive problem, and this sure is attack the problem and try to reduce it. So what could you do to reduce the cost of behavioral economics? And the answer is index or ETF. And the reason why it would index or ETF would help is because it’s boring. Right? You know, if you own an index fund, you don’t get excited about what happened in the market as anything like you would get excited about if you had just had five stocks or if you had two or three mutual funds and you were tracking those mutual funds because they changed more. The market as a whole, it kind of goes along in its own lumbering way. A slow wide river of flow over time. And you, yeah, there’s nothing to get excited about.

00:29:40 So you leave it alone. Huh? You leave it alone and you leave it alone. And it’s a little bit like when your mother said, don’t pick it, that scab let it heal by itself. Well, but mom, it itches. You’d just be a little bit tolerant and don’t itch it or don’t scratch it and it’ll heal faster. And sure enough, mother was right In the same way, if you index, you won’t be excited by the same things that other people get excited by. Then you’ll just sort of steadily flow through and have all the good results come your way. That’s it.

00:30:14 [Speaker Changed] Huh. Really, really interesting. So first of all, I have to tell you, I, I love this book. It’s totally digestible. It’s barely a hundred pages. I literally read it over a cup of tea and, and you’ve published 20 books before this. What, first of all, what led to this very short format? Why, why go so brief? I’m curious,

00:30:39 [Speaker Changed] Barry. It’s really an interesting experience. But for me, I love helping people with investing and I keep trying to think of how can I be helpful and what are the lessons that my children, grandchildren ought to learn? What are the lots that my favorite institutions ought to learn, my local church, whatever it is now, what could I offer that would be helpful? And I thought to myself, you know, the world has changed a lot and some rethinking of what’s the right way to invest might turn out to be a good idea. I should try penciling that out. And the more I tried to scratch it out for the church investment committee, I realized this is something that could easily be used by virtually everybody else. There are some major changes that have taken place and the world of investing is very different than it used to be. And the right way to deal with the world is really different than it used to be. And I owe it to other people because I’ve been blessed with this wonderful privilege of being able to learn from all kinds of people what’s going on in an investment world and how to deal with it and add it all together. I should put this together in this one last short book. And my wife laughed and said, you never get this down to only a hundred pages. I think that’s all it takes.

00:32:04 [Speaker Changed] You got pretty close. I think it’s like a hundred and something, 102, 104. You,

00:32:09 [Speaker Changed] You’re, you’re right there. Yeah. One of those pages is blank. And then there’s several pages that are half blank. So,

00:32:14 [Speaker Changed] Well I it it’s barely a hundred pages. So I, I love this quote from the book over the 20 years ending in mid 2023, investing in a broad based US total market equity fund produced net returns better than more than 90% of professionally managed stock funds that promised to beat the market. Really that’s the heart of, of the book, is that if you invest for 20 plus years, passive indexing, and we’ll talk about passive the phrase in a minute, but basic indexing ends up in the top decile.

00:32:52 [Speaker Changed] Yeah. And I, you’re talking about 20 years in. Many people say, oh gee, that’s a long time. Wait a minute, wait a minute, wait a minute. You start investing in your twenties, you’ll still be investing in your eighties. That’s a 60 year horizon. And if you’re lucky enough to do well enough, you might leave some to your children and grandchildren. So it might not be 60 years, it might be 80, a hundred, 120 years. Wow. Try to think about that long term because that is a marvelous privilege to have that long a time to be able to be an investor.

00:33:27 [Speaker Changed] And you, you cite the s and p research group, spiva, the average annual return of broad indexes was 1.8 percentage points better than the average actively managed funds. That’s nearly 2% compounding over time. That really adds up, doesn’t it? It

00:33:44 [Speaker Changed] Sure does. And compounding is really important for all of us to recognize that. Some people call it snowball, and I think that’s perfectly fine because as you roll a snowball, every time you roll it over, it gets much thicker, not just a little bit, much thicker than you do compounding at one, two, four, eight, sixteen, thirty two, sixty four, a hundred twenty eight. Those last rounds of compounding are really important. So for goodness sake, think about how can you get there so you’ll have those compoundings work for you.

00:34:20 [Speaker Changed] So we mentioned the phrase passive, which has come,

00:34:24 [Speaker Changed] Oh, please don’t do that. Which

00:34:25 [Speaker Changed] Comes with some baggage. But you describe what a historical anomaly, the phrase passive is it it really, why? Why don’t I let you explain? It really just comes from an odd legal usage. Te tell us a little bit about where the word passive came to be when it came to indexing. Glad to the

00:34:44 [Speaker Changed] Indexing is, to me the right word to use. Passive has such a negative connotation. I dunno about you, Barry, but I wouldn’t want anybody to describe me as passive. I’m gonna vote for so-and-so as president of the United States. That’s not gonna be because he’s passive. Passive is a negative term. However, if you’re an electrical engineer, it’s not a pejorative. There’s two parts. There’s two prongs or three prongs on the end of a wire. And there’s a wall socket that’s got either two holes or three holes depending on which electric system you have. The one that has the prongs is called the active part. The one that has the holes is called the passive part. And because indexing was created by a group of electrical engineers and mechanical engineers, they just used what they thought was the sensible terminology. And then other people who had not realized where it came from, saw it as being a negative. I don’t want to be passive. I want to have an active manager who go out there and really do something for me. That is a complete misunderstanding. And it really did terrible harm for index investing to be called passive.

00:36:01 [Speaker Changed] Let’s talk about some of the other things that index investing has been called. And I put together a short list. ’cause there’s been so much pushback to indexing. It’s been called Marxist Communist Socialist. It’s devouring capitalism. It’s a mania. It’s creating frightening risk for markets. It’s lobotomized investing a danger to the economy, a systemic risk, a bubble waiting to burst. It’s terrible for our economy. Why so much hate for index then? Well,

00:36:35 [Speaker Changed] If you were an active manager and you were life threatened by something that was a better product at a lower cost, you might have some negative commentary too.

00:36:44 [Speaker Changed] It, it’s just as simple as their livelihood is dependent on flows into active, and that’s where all the animus comes from.

00:36:51 [Speaker Changed] And it’s, it’s partly livelihood. It’s partly religious faith. It’s partly cultural conviction. It’s partly what I’ve done for most of these people would say, I’ve been doing it for 25 years and I want to keep doing it for 25 years. Oh, by the way, I get paid really well to do it. And I like that job

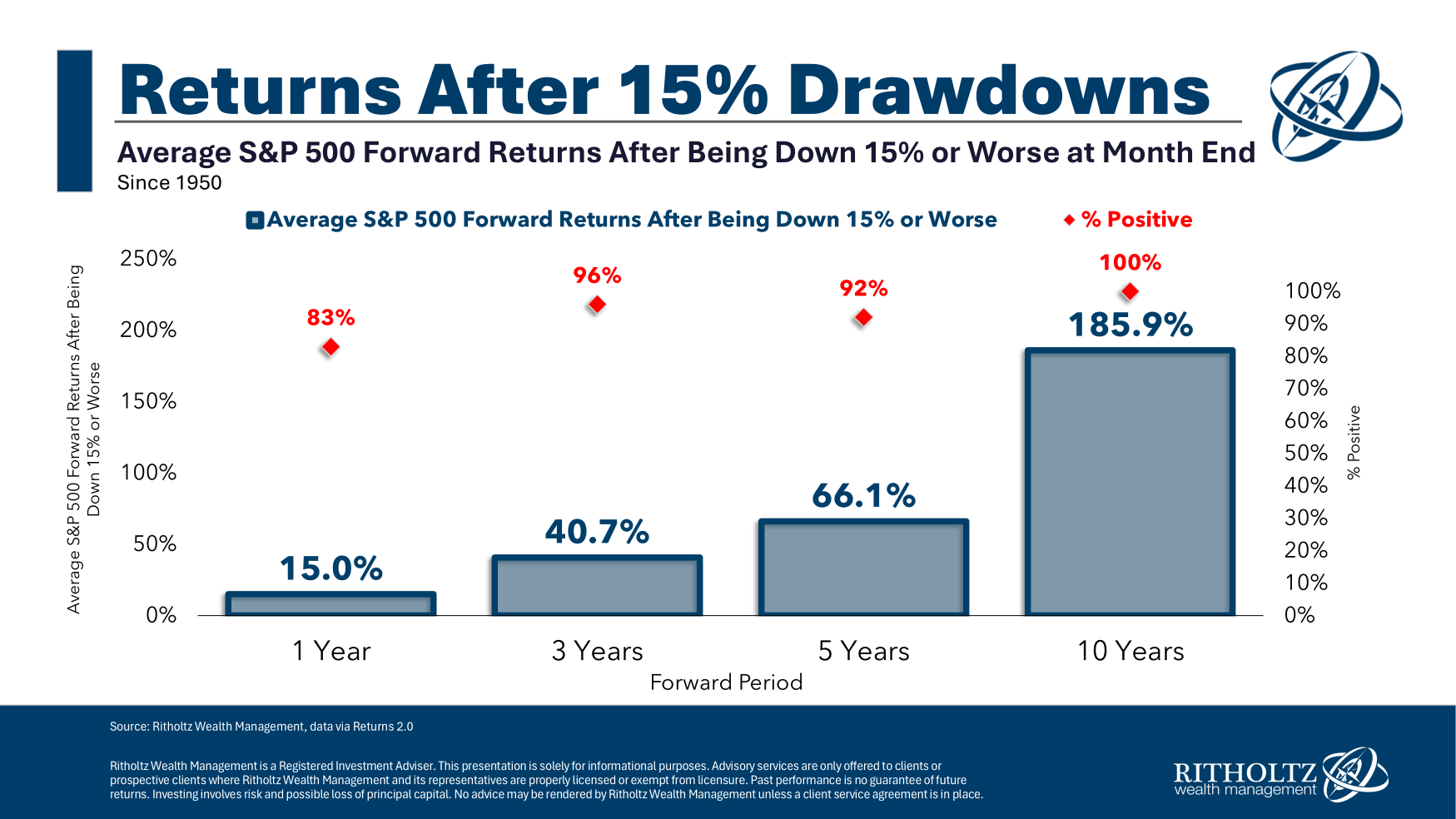

00:37:08 [Speaker Changed] To continue. Sure. You mentioned, we talked earlier about the temptation, the, that we’re surrounded by temptations to be wrong. I want to talk about some data in the book about what happens if you are wrong and out of the market during some of the best days. And the data point you used was 10,000 trading days over 26 years on average. That’s about 11.2% returns. So if you have money in broad market indices over 26 years, 10,000 trading sections, you’re averaging 11.2% annually. If you miss only the 10 best days, not a year, but over those 10,000 trading days, that 11.2% drops to 9.2%, 20 days down, seven point to 7.7% a year. And if you miss the 30 best days out of 10,000, the return goes from 11.2 to 6.4, almost a 500 basis point drop. That’s amazing. Tell us about that.

00:38:22 [Speaker Changed] Oh, first of all, you have to recognize when you select out the most extreme days, it does have a really big impact. The second thing is, when do those days come? And the best days usually come shortly after the worst days. Right? The bounce, the, Hey, wait a minute, this market is not as bad as everybody’s saying. It really does have terrific opportunity and that’s when the best days typically come. So the time that we all get frightened and all of us get unnerved is the wrong, the most wrong time to be taking action.

00:39:03 [Speaker Changed] And and the statistical basis is those 10 days are only 0.1% of total training sessions. But you’re giving up one fifth of the gains that that’s an amazing asymmetry

00:39:18 [Speaker Changed] And it’s a hell of a great lesson to learn. Hang in there steady. Eddie does pay off.

00:39:24 [Speaker Changed] Another quote from the book, why should investors care about the day-to- day or even month to month fluctuations in prices if they have no plans to sell anytime soon? That sounds so perfectly obvious when you hear it. Why are people so drawn into the noise?

00:39:42 [Speaker Changed] Well, when I advise people on investing, I always start with, what do you most want to accomplish? And then the second question is, when do you plan to sell your securities? And most people say, well, what do you mean when do I plan to sell? Well, when are you most likely to say, I need money out of my securities investment for life spending probably in retirement. Oh yeah. And then they’ll give you a date and then you say, and how far out into the future is that? And then really want to be difficult for somebody say, okay, that’s 43 years out into the future. Let’s go back 43 years. Tell me what you think was happening 43 years ago. Today’s date, 43 years ago. I have no idea. Why do you ask? Well, I’m asking because you have no idea and you have no idea 43 years into the future. And the reason for that is because you don’t care. It’s the long term trend that you care about and you care greatly about that. But you don’t care about the day to day to day fluctuations.

00:40:53 [Speaker Changed] So you, you sum up the book by pointing out every investor today has three great gifts, time compounding and ETF and indexing discuss

00:41:07 [Speaker Changed] Time to be able to have the experience of compounding where you each compounding round, you double what you had. Boy does it really pay off to benefit it for the long term and have saved early enough so that you compound a larger amount. But that leap from one to two is not very exciting. Two to four is not much. Four to eight’s, not really all that much. Eight to 16 starts to attract your attention. 16 to 32, that’s really something. 32 to 64 and to 128. Holy smokes. I want that last doubling. That’s really a payoff only way you get there. You start early and stay on course compounding away as best you can.

00:41:57 [Speaker Changed] You know, you, you people have pointed out, and I think you referenced this in the book, that as successful as Warren Buffet has been over his whole career because of the doubling, it depends on the rule of 72, but let’s say every seven or eight years, half of your gains have come in the most recent seven and a half, eight year era. And Warren’s now in his nineties, and the vast majority of his wealth have only happened in the past 10, 15 years. It’s kind of fascinating.

00:42:30 [Speaker Changed] Well, he’s a brilliant and wonderful human being, and all of us can learn great lessons from paying attention to what Warren says or has said. And his annual meetings are a treasure chest of opportunities to learn. But he did start as a teenager, not in his mid twenties, but in his early teens. And then he is not stopping at 65. He’s roaring right past that. And when you bolt on those extra years, it gives him a much larger playing field in which the double and double and redouble and redouble and all of us ought to pay attention to that one most powerful lesson. If you’ve got the time, the impact of compounding really is terrific. And the only way you get to be have the time is to do it yourself. Save enough early enough and stay with it long enough to let the compounding take place. But it’s inevitable. Power of compounding is just wonderful to have on your side.

00:43:34 [Speaker Changed] So three of the things I want to talk about from the book first, as alpha became harder and harder to achieve as it became more difficult to beat very good competition, the aspect of reducing costs, reducing fees, reducing taxes, became another way of generating better returns. Tell us a little bit about what led you to that conclusion and what firms like BlackRock and Vanguard have done to to further that belief system.

00:44:09 [Speaker Changed] Variance really candidly, just been pay attention to what the numbers say and pay attention to the data. And the data is so powerfully, consistently strong that active investing is a exciting idea. And in the right time and circumstance, the 1960s, it worked beautifully, but the circumstances now are so different that it doesn’t work beautifully. It works candidly, negatively, huh.

00:44:40 [Speaker Changed] Two other things I wanna go over. One is the concept of total financial portfolio. Meaning when you’re looking at your allocation, you should include the present value of your future social security payments and the equity value of your home as sort of bond-like. And that should help you shift your allocation a little away from bonds, a little more into equities. Tell us about that.

00:45:08 [Speaker Changed] Well, I think it’s one of those ideas that once it pops into your mind, you’ll never walk away from it. Most of us have no idea what the total value of our future stream of pay payouts from social security are. But you can do the calculation fairly simply. Most of us would be really impressed if they, if we realized how much is the real value of that future stream of payments that are coming from the best credit in the world. Federal government. Huh. So, and that’s inflation protected. So it’s even better than most people would imagine. That’s the single most valuable asset for most people. And the second most valuable asset for most people is the value of their home. And I know people would say their first reactions, but I’m not gonna sell my home. I’m gonna continue to live there. Fine, true. But someday either your children or your grandchildren will say, we don’t really wanna live in that same house, so we’re going to sell it.

00:46:08 So it does have an economic value. And it will be realized at some point down the line, take those two and put them side by side with your securities. And most people would say, my God, I’ve got more in the way of fixed income and fixed in bond equivalents than I had ever imagined. I think I ought to be careful in my securities part of the portfolio to rethink things and probably be substantially more committed to equities in my securities portfolio because I’ve got these other things that I was never counting on before. But now that I’ve been told about it, I really want to include that as my understanding to the total picture.

00:46:50 [Speaker Changed] And, and I like the concept of outside the market decisions versus inside the market decisions. Explain the difference between the two.

00:47:00 [Speaker Changed] Well, outside market decisions have to do with what’s changed in your life. Most obvious being when you retire, but sometimes it’s when you get a better job and a higher pay, or even you get a signif significant bonus because of the wonderful achievement that you’d had during the particular year when your circumstances get changed. Oh, and getting married is another real change. When the circumstances change, you really ought to rethink your investment program just to be sure that it’s really right for your present total picture,

00:47:38 [Speaker Changed] Ma. Makes a lot of sense. I know I only have you for a few more minutes. Let me jump to three of my favorite questions that I ask all my guests. Starting with, what are some of your favorite books? What are you reading right now?

00:47:54 [Speaker Changed] My favorite books tend to be history. And the one that I’ve most recently read is a wonderful biography of Jack Kennedy as President and the things that he did that made America the most popular country in the world.

00:48:13 [Speaker Changed] And our last two questions. What advice would you give to a recent college grad interested in a career in investing?

00:48:21 [Speaker Changed] Think about what really motivates you to be interested in investing. If it’s because it’s a high income field, that’s okay, but candidly, it’s not an inspiration and you only have one life to lead Is, is it your desire to lead your life making money or doing something that you would say was at the end of your life, I’m so proud of, have what I did, or I’m so glad I did what I did. If you’re thinking about investing because it’s a profession where you help people be more successful at achieving their objectives, then candidly, you could have a fabulous time. It won’t come because you beat the market, but that’s not the problem for most people. For most people, beating the market is very clearly secondary to what’s their real need, which is to think through what are their objectives, what are their financial resources, and how can they put those together into the best for them Investment program. And the same thing is true for every college, every hospital, every college, church, every organization that has an endowment needs to think carefully about what is the real purpose of the money and how can we do the best for our long-term success by the structure of the portfolio that we have.

00:49:44 [Speaker Changed] And our final question, what do you know about the world of investing today that would’ve been really useful back in the 1960s when you were working for the Rockefellers?

00:49:55 [Speaker Changed] Oh boy. First that the whole world is gonna be changing. So don’t stay with what you think is really great about the early 1960s because all of that is gonna be upended and all the lessons that you would think were just great about how to do things in the early 1960s. We’ll work against you then. By the time you get to the this time of the year, you’ll be making mistakes, one after another, after another, after another by doing things that are just completely out of date. And the world of investing will change more than most fields will change. Computer technology will change more. Airplane travel will change more. But candidly, investing is gonna change so much that if you take the lessons that you’re learning for how to do it in the sixties and try to transport those into the 2000 and twenties, you’re gonna pay a terrible price. Don’t do it. Don’t do it.

00:50:55 [Speaker Changed] Thank you, Charlie, for sharing all of your wisdom and insights. I really greatly appreciate it. We have been speaking with Charlie Ellis talking about his new book, rethinking Investing, a very short guide to very long term Investing. If you enjoyed this conversation, check out any of the 500 or so we’ve done over the past 10 years. You can find those at Bloomberg, iTunes, Spotify, YouTube, wherever you find your favorite podcast. And be sure and check out my new book, how Not to Invest the Bad Ideas, numbers, and Behavior that Destroys Wealth. I would be remiss if I did not thank the crack team that helps put these conversations together each week. Andrew Davin is my audio engineer. Anna Luke is my producer. Sean Russo is my researcher. Sage Bauman is the head of podcasts at Bloomberg. I’m Barry Riol. You’ve been listening to Masters in Business on Bloomberg Radio.

~~~

The post Transcript: Charley Ellis on Rethinking Investing appeared first on The Big Picture.