The Strait of Hormuz has energy markets nervous about Iran, but there are alternate routes around the chokepoint

About 20 million barrels of oil a day flow through the Strait of Hormuz, or the equivalent of 20% of global petroleum liquids consumption.

- Iran’s military capabilities have been diminished by punishing strikes from Israel, but Tehran still has significant leverage as it weighs a response to the U.S. bombing of its nuclear facilities over the weekend. A top target would be the Strait of Hormuz, a critical chokepoint in the global energy trade that could be blocked by Iran. But alternative routes exist that could help mitigate any closure.

All eyes are on the Strait of Hormuz as Tehran considers how it will respond to the U.S. bombing of Iran’s nuclear facilities over the weekend.

While Iran’s military capabilities have been degraded by punishing Israeli airstrikes that began a week and a half ago, the Islamic republic retains significant leverage elsewhere.

A top target would be the Strait of Hormuz, a critical chokepoint in the global energy trade that could be blocked by Iran. Iranian lawmakers approved its closure after the U.S. attack, but security officials have yet to sign off on it and the waterway remained open on Monday, helping send oil prices lower. Still, some tankers are steering away from the strait anyway.

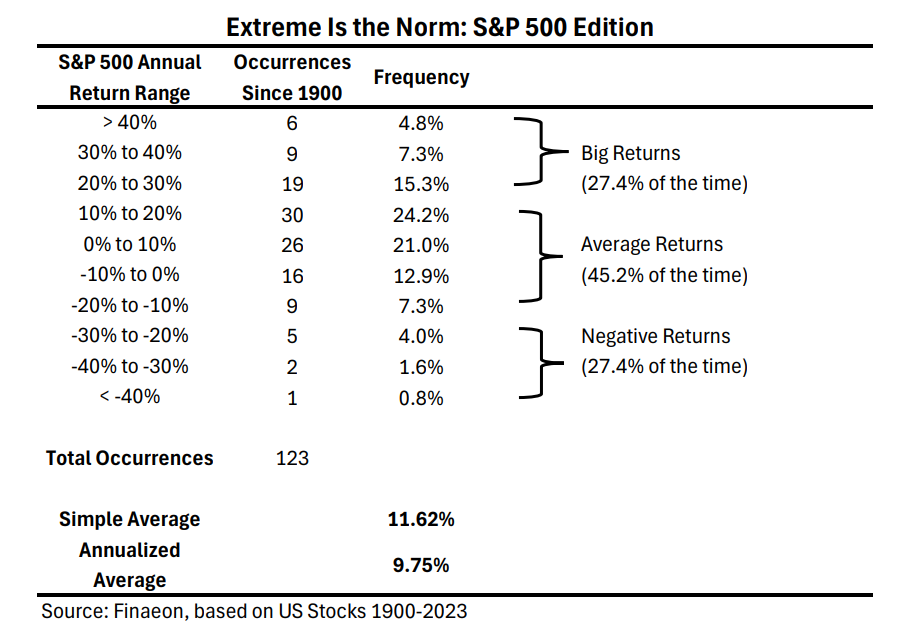

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), an average of 20 million barrels of oil a day flow through the strait, or the equivalent of about 20% of global petroleum liquids consumption and about one-quarter of total global seaborne oil trade.

In addition to oil, about one-fifth of global liquefied natural gas trade also passed through the Strait of Hormuz last year, primarily from Qatar, EIA says.

Given its importance to the energy trade, the strait’s closure would cause massive turmoil in markets. In a note earlier this month, George Saravelos, head of FX research at Deutsche Bank, estimated that the worst-case scenario—a complete disruption to Iranian oil supplies and a closure of the Strait of Hormuz—could send oil price above $120 per barrel. That would represent a 56% increase over the current price of Brent crude.

Any closure might entail use of mines, patrol boats, aircraft, cruise missiles, and diesel submarines. While the U.S. Navy has deployed a formidable array of ships to the region, clearing the strait could take weeks or months.

But there are alternative routes that could help mitigate some of the effects of any closure.

For example, state-run energy giant Saudi Aramco operates a crude oil pipeline that runs east and west from the Abqaiq oil processing center near the Persian Gulf to the Yanbu port on the Red Sea, according to EIA.

The United Arab Emirates operates another pipeline that bypasses the Strait of Hormuz by linking onshore oil fields to the Fujairah export terminal in the Gulf of Oman.

EIA estimates that the Saudi and UAE pipelines could be used to divert 2.6 million barrels per day from the Strait of Hormuz.

That compares with 5.5 million barrels per day of crude and condensate that Saudi Arabia exported through the strait last year.

Iran also has a pipeline and export terminal on the Gulf of Oman that could bypass the Strait of Hormuz. The pipeline’s capacity is about 300,000 barrels per day, but its actual use has been far less than that. During the summer of 2024, Iran exported fewer than 70,000 barrels per day through that alternate route and stopped loading cargoes after September 2024, according to the EIA.

By contrast, the vast majority of Iran’s oil exports, which averaged about 1.5 million barrels per day last year, go through the Strait of Hormuz.

Many analysts see an Iranian closure of the strait as unlikely since doing so would devastate its own economy in the process and trigger a potentially catastrophic response from the U.S.

In a column in Foreign Affairs magazine earlier this month, Kenneth Pollack, a former CIA Persian Gulf military analyst and former director for Persian Gulf affairs at the National Security Council, said there’s a low probability Iran would close the strait.

That’s because Iran would quickly go from a “sympathetic victim to a dangerous nemesis in the eyes of most other countries,” while Western countries and perhaps even China would use force to reopen the strait, he predicted.

“And Tehran would have to worry that such a reckless threat to the world’s economies would convince Washington that the Iranian regime had to be removed,” Pollack added. “That fear is surely greater with U.S. President Donald Trump—who ordered the death of Iranian general Qassem Soleimani in January 2020—back in office.”

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com