How a warehouse innovator quietly built a corporate giant

The longtime Fortune 500 CEO credits his company's success to "cool insights, some dumb luck, and some decisions that were well thought through."

Hamid Moghadam thinks of life in 14-year cycles. In 1983, he cofounded AMB Property Corporation to invest in offices, industrial parks, and shopping centers and took it public 14 years later. In 2011, he merged the company with his biggest competitor to form Prologis, the world’s largest industrial property owner with $8.2 billion in revenue and 1.3 billion square feet of warehouses and logistics facilities in its portfolio. Now, 14 years after the merger that put Prologis on the path to be No. 463 on the Fortune 500 and one of the World’s Most Admired Companies, Moghadam is making another pivot, at the end of the year he will hand the reins to President Dan Letter while staying on as executive chairman. In an interview with Fortune as part of a series of conversations with Fortune 500 CEOs, Moghadam reflects on succession, leadership, logistics, and why a chaotic trade environment boosts his business—even though, as he puts it, “I don’t like to make our money that way.”

The following has been condensed and edited for clarity.

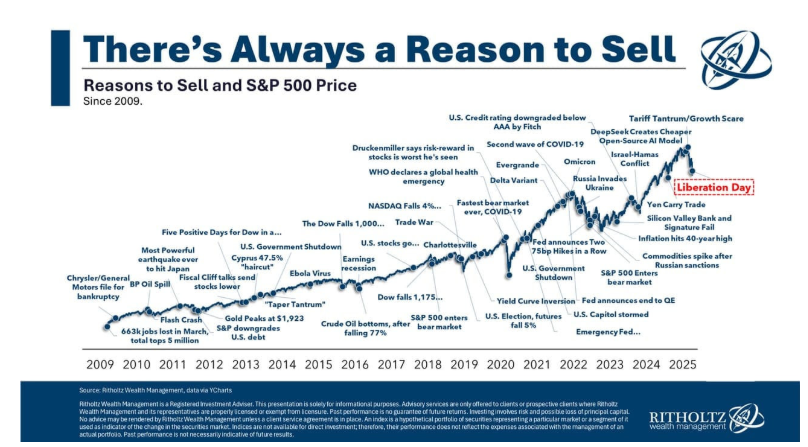

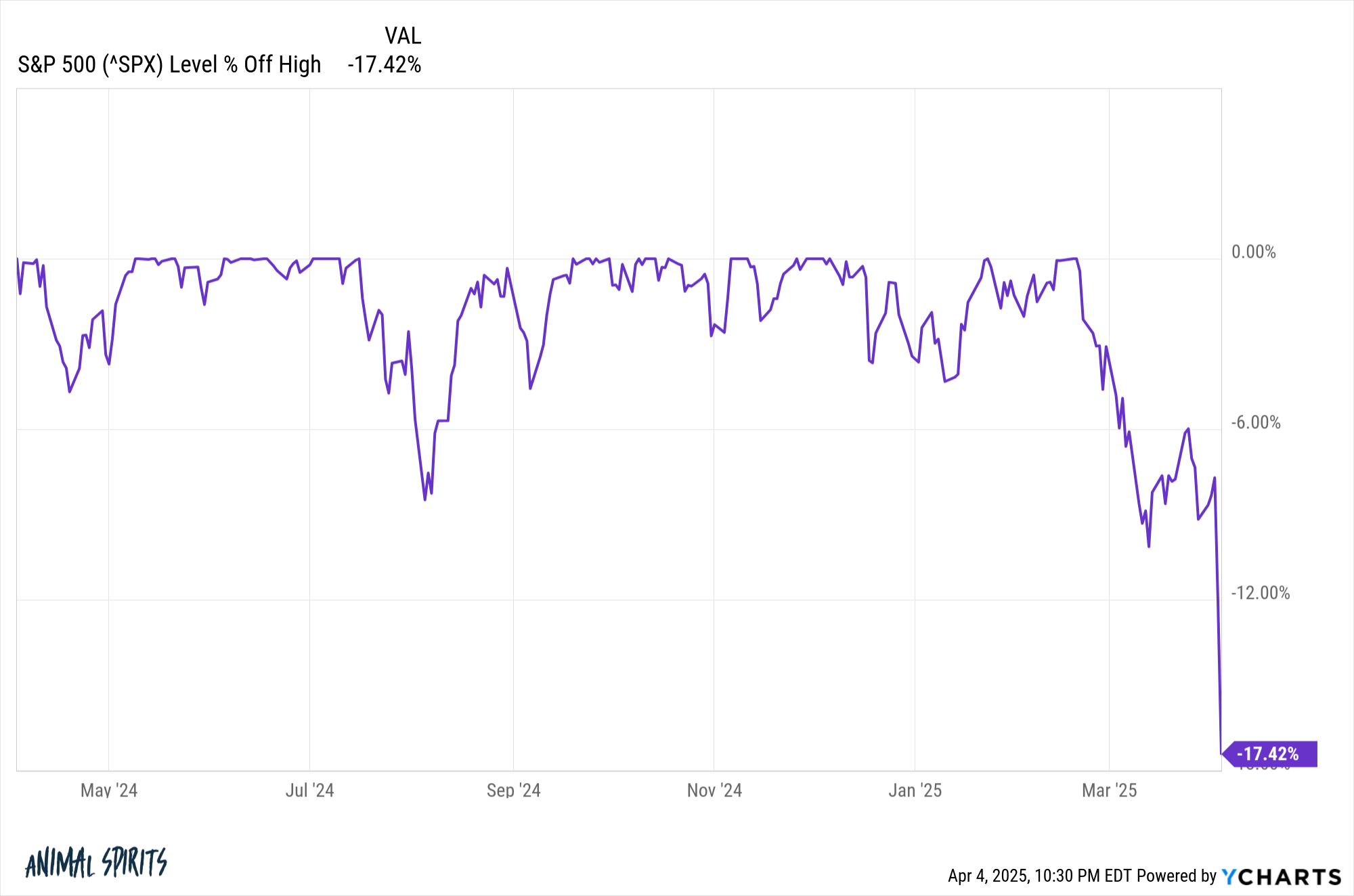

You must be feeling the impact of this tariff war.

These policies and this uncertainty are both inflationary and growth reducing. But whether the container is coming from Shanghai or Vietnam or somewhere else, there's no difference. When any kind of disruption happens that raises havoc with the supply chain—meaning the predictable supply chain that’s been optimized by engineers goes out the window—people want to have all kinds of extra inventory everywhere to deal with the uncertainty. In the short term, it’s a demand booster for our business, but I don’t like to make our money that way.

What prompted you to step down as CEO at the end of this year?

You're going to be surprised by the lack of sophistication in this decision-making. I started and ran an entrepreneurial private company called AMB for 14 years before taking it public. I ran that for 14 years until 2011, when we bought our biggest competitor. They kind of blew themselves up during global financial crisis and that opened the door for us to buy it, so that will be another 14 years by the end of 2025.

Every life has chapters. Is there something distinctive about 14 years?

Well, I grew up in Iran and was 14 when I went to boarding school in Europe. But the education part only took seven years, so that that sort of breaks the rule.

The second reason is I did not want to have a seven in front of my age doing this job. I'm going to be 69 and, honestly, the reason for it is that I've seen too many CEOs, and particularly founders, hang around too long. They've really destroyed their company, and they've stopped having fun. You don't have the same energy. You don't have the same ability to travel or recover from travel the way you did. I think people generally stay too long in these kinds of jobs.

It's time for a whole new generation of leaders with a whole new generation of relationships with their peers to take over the business. My job in the last four or five years has been to clear the deck of the old management team and start the process of transitioning all the executive committee members. That started five years ago. With me gone, he will have completely his own team.

“In the short term, [trade woes are] a demand booster for our business, but I don’t like to make our money that way.”Hamid Moghadam, CEO, Prologis

Did you have some role model for how to do this?

My partners and I, about 30 years ago, sat down and said, “Why are we working so hard building this entrepreneurial company? What do we care about at the end of the day?” The notion of enduring excellence popped up. This was around the time that Arthur Andersen had blown up. Goldman Sachs had gone through a lot of problems. McKinsey had its CEO issue.

But Goldman, Mackenzie, Arthur Anderson, they're all service firms, these icons of organizations that have gone through generational change and remained excellent. There was no example of that in real estate. None. Zero. Because real estate people build up when times are good, they over lever, they crash, and then they start all over, and so it goes. Our goal was to build a company of enduring excellence. We even defined it by what it means to customers, to our employees, to our investors, and to the communities in which we operate. We were very clinical about the objective and how to measure it? And that's pretty much defined everything we've done since then. The only north star is what’s going to ensure excellence in the long term for all those constituencies.

One of the hardest things to do is replace yourself.

I just felt in my bones that it was the right thing for the company. I didn't want to do it while we were in COVID. Dan and I spent two years working very closely together, and I've given up more and more of this stuff. You know, the CEO job is about vision and strategy and all that. But I spend 2% of my time on that. If you don't get that stuff right, the other 98% doesn't matter. But 98% of success is about execution, and execution has to do with people: recruiting, where you move somebody, creating a dynamic environment.

What made you think Dan should be the next CEO?

He joined us as a very, very junior young guy in our construction department in Chicago. Maybe five years into his career, when he was in charge of making deals and deployment and all that kind of stuff, I vetoed a decision. Our investment committee makes 300 decisions a year, and this was a $30 million investment, which is not a big number for us. I exercised my veto for the first time, and it was his deal. I did it because of some patterns that have been ingrained in my brain over how Silicon Valley works. This particular investment reeked of all the things that have gone wrong before in these cycles and all that, and I just didn't want to do it. Most people would have left it there, but Dan came back after about a week of looking at all the questions that I asked and made the case as to why I was worried about the wrong thing. And I changed my mind. The fact that this young guy had the courage to do that, that he was an independent thinker, that's really important. So that got him on my radar. By the way, we made a ton of money on that deal. So, he was right, and I was wrong.

One challenge for any new CEO is having your former boss work down the hall.

So, here's what I did. I moved him into the office literally next to mine a year and a half ago, with glass in between. We're basically joined at the hip and always communicating across the glass. Now, I'm relocating my residency and am in San Francisco, maybe 20% of the time. That physical separation was important, and I'm going to make sure he moves into my larger conference room and makes that his office the day he takes over. So, we've gone through a gradual transition, physically, too.

Could you imagine ever retiring? Most people I talk to in your position say, “No.”

No. I've got way too many interests. I tell you what I'm not going to do: I am not going to go on corporate boards. I stopped doing public company boards about 20 years because, frankly, I don't find that stimulating. It's more of an oversight function and I just want to get things done. If you have the right CEO and they're doing the job, you’ve got to support them. If you don't like what they're doing, you should change them. I've also gotten off of all my charitable boards. I'm on no Stanford board for the first time in 30 years. I'm still doing a lot of philanthropy, but I'm doing it in organizations where I trust and know the leadership and not trying to pretend like I'm from the board that can really influence the direction. They say they want your input, but they really want your financial support and your Rolodex.

So what will you do?

What I'm going to do more of is mentor young entrepreneurs. I've made a lot of investments in technology, particularly with the deal flow coming from the Iranian American community. They're very entrepreneurial in tech and all that. And I helped them over the years, about a dozen of them. You can really move the needle on small, young companies, and help them avoid disaster or get on a really fast wave. And I just like the immediate manual transmission of that action, what happens when the rubber hits the road. And I'm going to spend more time on my own family office. Frankly, I want to enjoy life a little bit more, travel to places other than Congress or hotels.

The advice I've gotten from people is don't overcommit because busy people like me, when they step off, they get sort of nervous that maybe I'm not important, or nobody cares about me or they want to still be in the game. I'm not going to do that.

How much time do you want to spend as a chairman?

I think I want to get down to a day, the equivalent of a day or two a week, which may be nothing for a month and a couple of weeks. You know, the people and organizational insights are going to have a very short shelf life, because I'm not going to know the new people coming. On some of the external relationships, the pattern recognition skills, some of the sounding board things, I think I can add more. I ideally want to do it for two to three years. And by the way, I'm not going to sell my stock.

I have held on to 95% of that. I think it's a religious thing for me. If you're a CEO of the company, and you're getting on the call every quarter, talking to investors about your company and all that, you got to be eating your own cooking.

There must be moments of reflection as you make this transition.

There are lots of those. I think of why I chose to come to Stanford Business School, having gone to school back east, and it was because of the blizzard of 78.

I'm Canadian. You're speaking my language there.

I could have just as easily gone to Harvard Business School. That got me on the West Coast, which was totally serendipitous. I wouldn't have met my partners if I had not been on here. I wouldn’t have started this business. I wouldn't have married my wife. I wouldn't have started my family. Some decisions I handle randomly. Some are more deliberate, like we decided to take a very successful private equity real estate business and do something that nobody had done in the world, which is to combine the GP and the LPs and take that business public. Nobody had done before. A couple of people had done private equity firms have not kind of done it. You know, 1015, 20 years later, TPG, KKR, those guys,

Sam Zell did it a couple of months after we did ours with equity office property. So, it's great to have done something that nobody did before that really worked and became the playbook for other people. We decided to sell retail in 1999 because I met a man who was starting a company called Webvan.

The online grocery company that went bankrupt when the dot.com bubble burst. Louis Borders!

Yes. Louis Borders. His vision just scared the bejesus out of me. At that time, we also owned the retail shopping center business and, literally because of that, in ’99, we sold our entire retail division, which was a third the company. We doubled down on logistics. So were some cool insights, some dumb luck, and some decisions that were well thought through. I'm really proud of getting more things right than wrong.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com