As the Fed devises its new strategy, Powell sees an economy with ‘more volatile’ inflation

Every five years the Federal Reserve reconsiders its framework for monetary policy. This time it will have to consider lessons from the pandemic and an uncertain future.

- In discussing the outlook for the U.S. economy Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell said he saw a future with the possibility of ups and downs in inflation. He added that he also saw an increased likelihood of “supply shocks” that could disrupt American businesses.

Every five years the Federal Reserve reexamines the framework it uses to ensure its keeping the U.S. economy on a path of full employment and stable prices—a congressionally mandated double goal it must achieve with just a few tools, while keeping stock of evolving macroeconomic conditions, the labor market, and GDP growth. The strategy informs how exactly the Fed will achieve both its goals, which are the bedrock of a stable economy.

On Thursday, as the Fed began a conference to discuss how it would maintain maximum employment and 2% long-term inflation, the prognosis was: more turbulence.

“We may be entering a period of more frequent and potentially more persistent supply shocks, a difficult challenge for the economy and for central banks,” Fed chair Jerome Powell said during the conference’s opening remarks.

Powell did not discuss in detail the current state of the economy, instead focusing on its evolution from the post-Great Recession recovery to today. During the recovery period interest rates were extremely low, while the Fed’s benchmark rate now sits between 4.25% and 4.5%. Rates are higher because inflation could be more unpredictable going forward, Powell said.

“Higher real rates may also reflect the possibility that inflation could be more volatile going forward than during the inter-crisis period of the 2010s,” he said.

In looking back at the past five years under which the Fed’s current framework informed monetary policy, Powell discussed the COVID-19 pandemic, which hit the world shortly after the current strategy was implemented. At the time the U.S. economy had been stuck in over a decade with low growth, low inflation, and low interest rates. As a result, the plan had been for monetary policy to try and achieve an “intentional, moderate” overshoot of the 2% inflation target in periods when it was below that level, Powell said.

Then the pandemic hit and completely disrupted those plans.

“There was nothing intentional or moderate about the global inflation that arrived a few months after we announced our changes to the consensus statement,” Powell said, referring to the Fed’s name for its five-year plans.

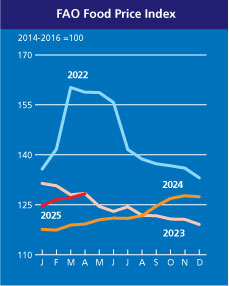

Annual inflation eventually rose as high as 9.1% in the summer of 2022. To curb the soaring price increases, the Fed started raising rates. What happened next was also unexpected. As rates rose and inflation came down, unemployment didn’t spike, as conventional economic wisdom dictated it would. Instead unemployment remained at its historically low levels of around 3.5%.

“In a welcome and historically unusual result…this disinflation has come without the sharp increase in unemployment that has often accompanied a campaign of rate hikes to reduce inflation,” Powell said.

Those changes will factor into the Fed’s new strategy, Powell said. “The economic environment has changed significantly since 2020 in our review, which will reflect our assessment of those changes,” he said.

However, one thing that will remain consistent is the need to ground what the Fed refers to as “long-term inflation expectations.”

“While the framework must evolve, some elements of it are timeless,” Powell said. “Policymakers emerged from the great inflation with a clear understanding that it was essential to anchor inflation expectations at an appropriately low level.”

Inflation expectations is a critical measure because it describes how the Fed, investors, economists, and businesses believe inflation will be in the future. Even if price increases tip up or down in a given monthly report, if businesses and consumers expect them to stay steady in the future, they generally still keep spending. Businesses are more likely to make major capital expenditures and consumers won’t hunker down in anticipation of a downturn if they believe the economy will be ok in the long run. During the rampant uncertainty and market tumult of April, Powell regularly pointed to the fact that long-term inflation expectations had remained steady.

Keeping inflation expectations level was key to the U.S.’s post-pandemic recovery, Powell said.

“Since the Great Inflation, the U.S. economy has had three of its four longest expansions on record,” Powell said. “Anchored expectations played a key role in facilitating these expansions. More recently, without that anchor, it would not have been possible to achieve a roughly five percentage point disinflation without a spike in unemployment.”

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com