Trump’s tariffs put American growth and prosperity at risk—and raise the likelihood of a recession

Tariffs may feel like action, but they lead to stagnation and economic crises in the long run.

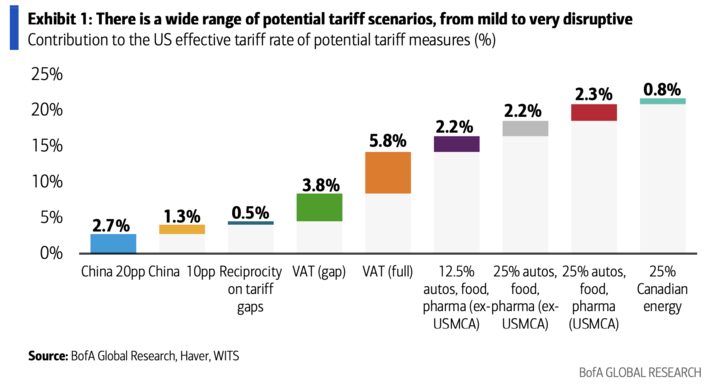

President Trump’s sweeping new tariffs, announced yesterday, signal not just their embrace as a negotiating tactic, but a dramatic reordering of the global economy—one that could reshape entire industries and redefine how the country competes, trades, and grows.

As the United States drifts further toward protectionism, with growing bipartisan support for tariffs and industrial policy, it is worth remembering a cautionary tale from 20th-century development economics. Two regions—Latin America and East Asia—faced similar postwar challenges, yet took starkly different paths. One embraced tariffs and import substitution; the other, global markets and export discipline. The outcome was a decades-long divergence in growth and prosperity. Today, the U.S. risks forgetting which path led to dynamism and which to meager growth.

In the aftermath of World War II, Latin American nations, aiming to reduce dependence on foreign goods, adopted a model known as import-substitution industrialization (ISI). Under ISI, governments imposed steep tariffs, quotas, and currency controls to shield domestic industries from foreign competition. The goal was economic independence and the nurturing of homegrown industries. For a brief period, the strategy appeared to work: Factories opened, urban employment expanded, and GDP grew.

But the initial gains masked long-term weaknesses. Shielded from competition, many industries became inefficient and technologically stagnant. Government protection encouraged higher prices and discouraged innovation and productivity gains. Rather than fostering competitiveness, ISI created complacency. Over time, trade deficits widened, inflation soared, and foreign debt ballooned. By the 1980s, Latin America entered what is now known as the “lost decade,” marked by economic crisis, stagnation, and painful structural adjustment to return to the path of economic liberalization.

East Asia chose a different route. Countries like Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and later China embraced export-oriented industrialization. While governments still played a central role in economic planning, the focus was not on sheltering firms but on preparing them to compete globally. This embrace of economic liberalization—coupled with targeted state support—unlocked rapid industrial growth, expanded access to global markets, and catalyzed the transition from low-wage manufacturing to high-tech, high-value industries.

This strategy brought with it the discipline of international markets. Companies had to produce high-quality goods at globally competitive prices or exit the market. Governments invested in education, infrastructure, and technology to support this transition. Over time, East Asian countries climbed the value chain—from textiles to electronics to high-end manufacturing. Their economies expanded, poverty receded, and innovation flourished.

The contrast could not be starker. From 1960 to 2000, East Asia’s per capita GDP grew at about three times the rate of Latin America’s. South Korea, once poorer than Bolivia, surpassed many European nations in income and technological sophistication. Meanwhile, Latin America became a case study in how protectionism can lead to economic sclerosis.

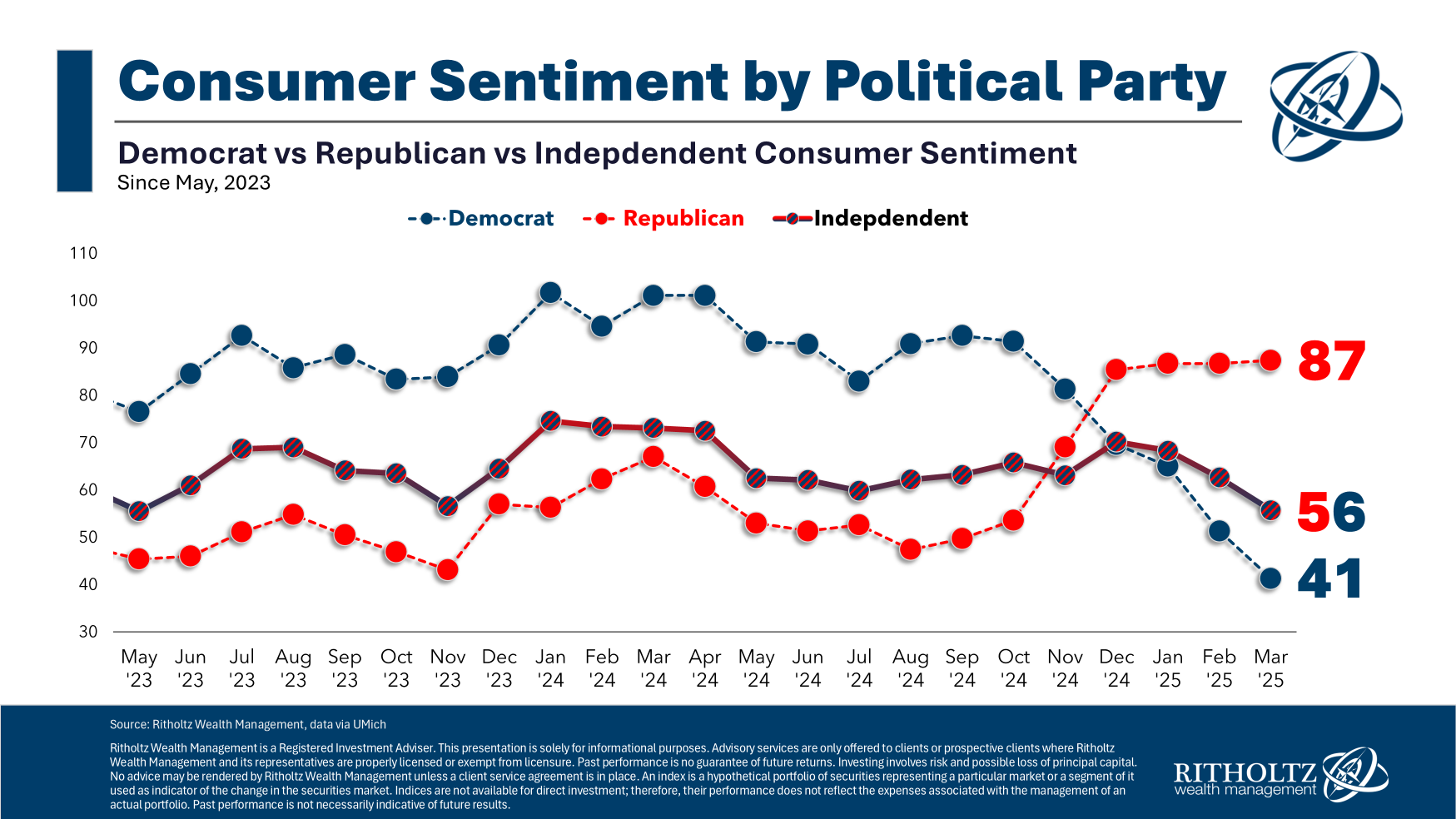

Why should Americans care? Because some of the same arguments used to justify Latin America’s ISI are now being recycled in Washington. The impulse to reshore manufacturing and impose broad tariffs echoes the rhetoric of self-sufficiency and industrial revival. These policies may serve legitimate goals, such as national security, employment creation, or supply chain resilience. But as currently implemented they risk producing the very stagnation they are meant to avert.

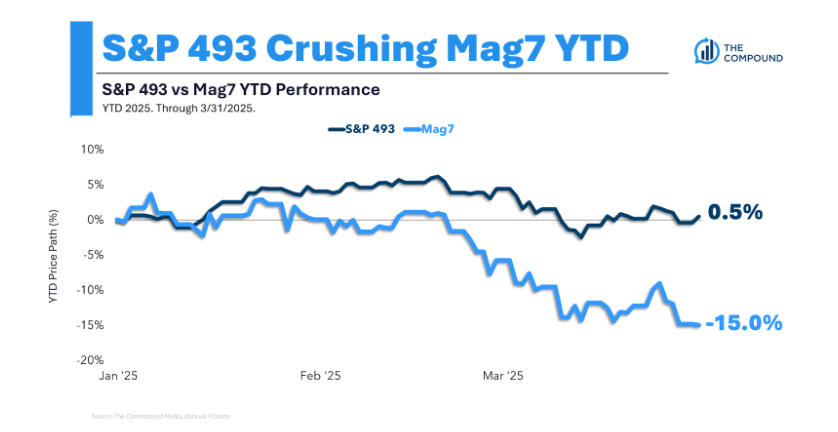

Consider recent U.S. tariff policy, including the 10% across-the-board tariffs and higher reciprocal ones on China and the EU—among others—announced by President Trump yesterday. While aimed at protecting domestic industries from unfair foreign competition, many tariffs function as blanket shields rather than surgical tools. They raise input costs for American firms, provoke retaliatory measures, and often fail to spur significant domestic investment. The lesson from Latin America is that artificially shielding industries brings about a short-term mirage of prosperity that only postpones the inevitable reckoning with global competitiveness.

East Asia, by contrast, used state power not to insulate firms indefinitely, but to push them into global arenas. Export requirements and international benchmarking were key features of their success. These governments bet on their industries not by sheltering them from failure, but by giving them the tools to succeed.

The United States, with its vast internal market and innovation ecosystem, is not Latin America. But it is not immune to the dangers of creeping economic nationalism. Tariffs can be politically seductive and temporarily popular. Yet, by taking away incentives for productivity, innovation, and global engagement, they can calcify industries, undermine competitiveness, and erode long-term growth.

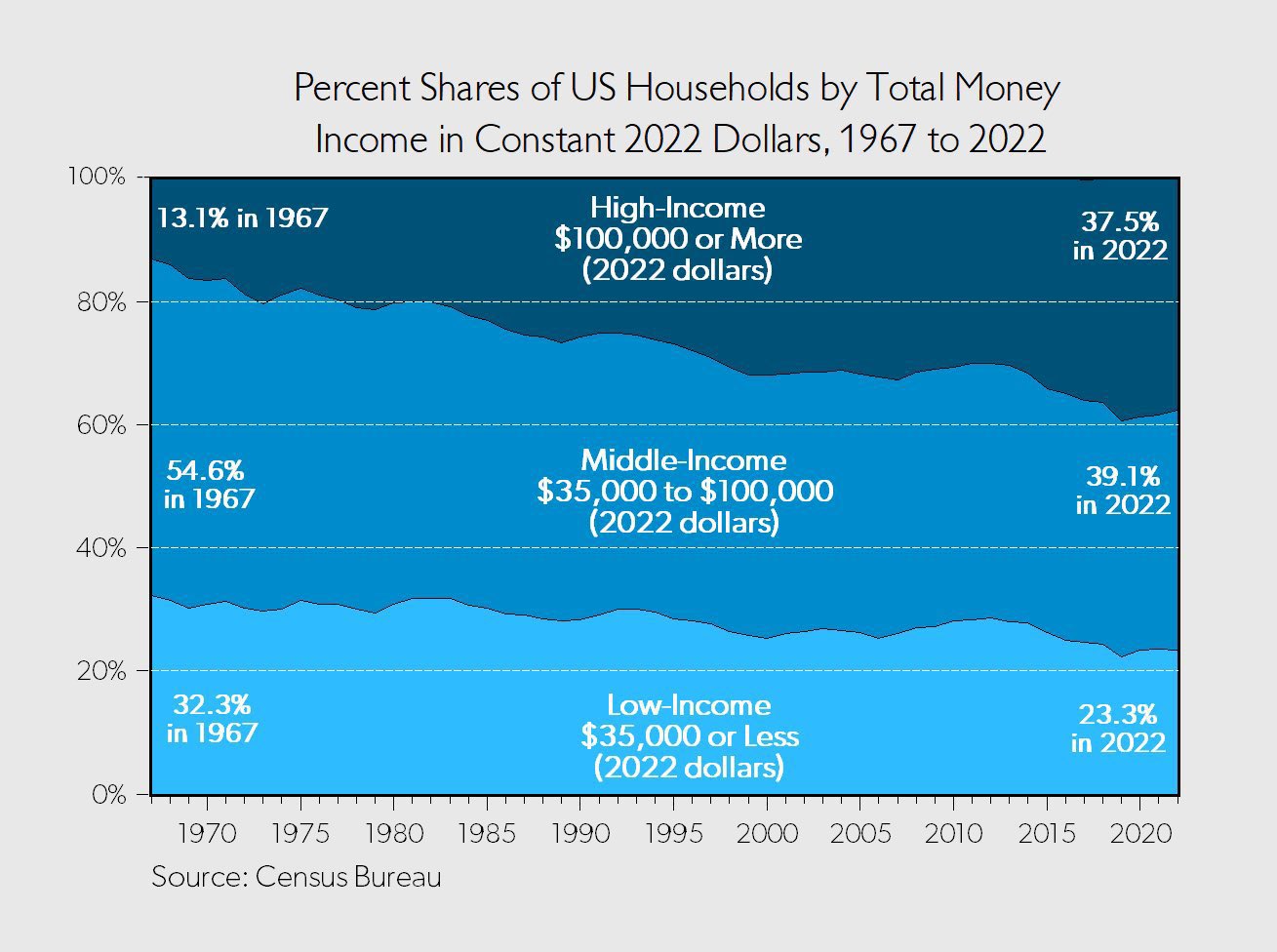

Tariffs may succeed in bringing some jobs back to U.S. soil, but they are hardly a panacea. Many of the jobs lost in American manufacturing over the past several decades were not outsourced—they were automated. Robots and software, not just foreign competition, have reshaped the industrial workforce. Without a strategy that confronts the realities of technological change—through workforce development, reskilling, and incentives for innovation—tariff-driven policies risk reviving industries in form but not in substance. Some jobs may return, but not in the numbers or types that matter most for middle-class revival.

As policymakers navigate a turbulent geopolitical environment and respond to rising economic insecurity, the temptation to turn inward will grow. But history offers clear lessons. Tariffs may feel like action, but they are a detour from development.

Latin America learned this the hard way. East Asia offers a blueprint for how to harness markets, discipline, and state capacity to drive transformation. The United States must choose wisely. The stakes are too high to get it wrong.

The opinions expressed in Fortune.com commentary pieces are solely the views of their authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of Fortune.

Read more:

- Trump is knowingly steering the economy off the cliff with tariffs

- Tariffs won’t make America great again: Export-Import Bank’s former chairman and president

- Trump’s tariffs are flawed and contradictory—and the ‘Mar-a-Lago accord’ is suited for the trash bin

- Trump’s tariffs program is based on flawed assumptions about the trade deficit

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com