Trump’s tariffs are not ‘common sense’—and they’re putting America’s credibility and ‘exorbitant privilege’ at risk

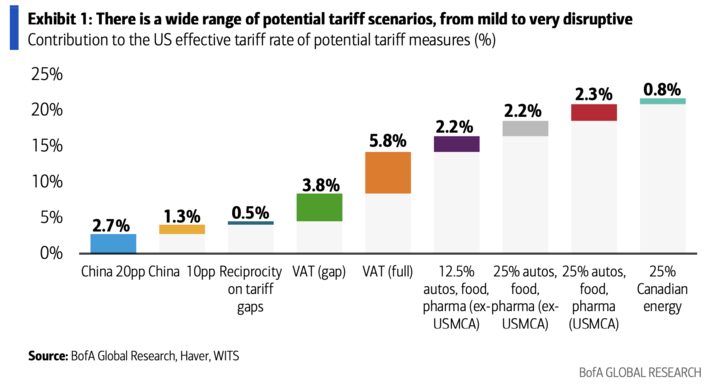

The tariffs, which are taxes on international transactions, are destroying trillions in U.S. wealth, with the worst still to come.

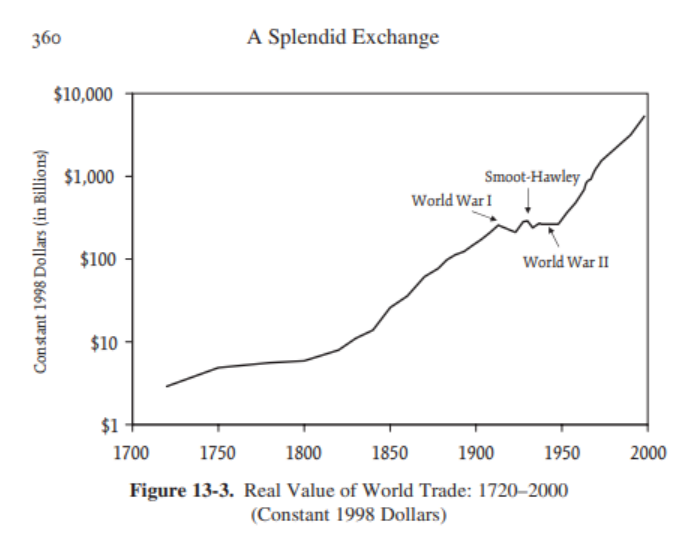

Among economists, a wide range of opinions prevails, with perhaps one exception: the embrace of free trade. Countries that trade freely produce more, consume more, and have higher incomes. Not surprisingly, economists generally oppose tariffs, which are nothing more than a tax on international transactions. They are beggar-thy-neighbor policies, used by countries who think they can boost their own economies by leaving other countries worse off.

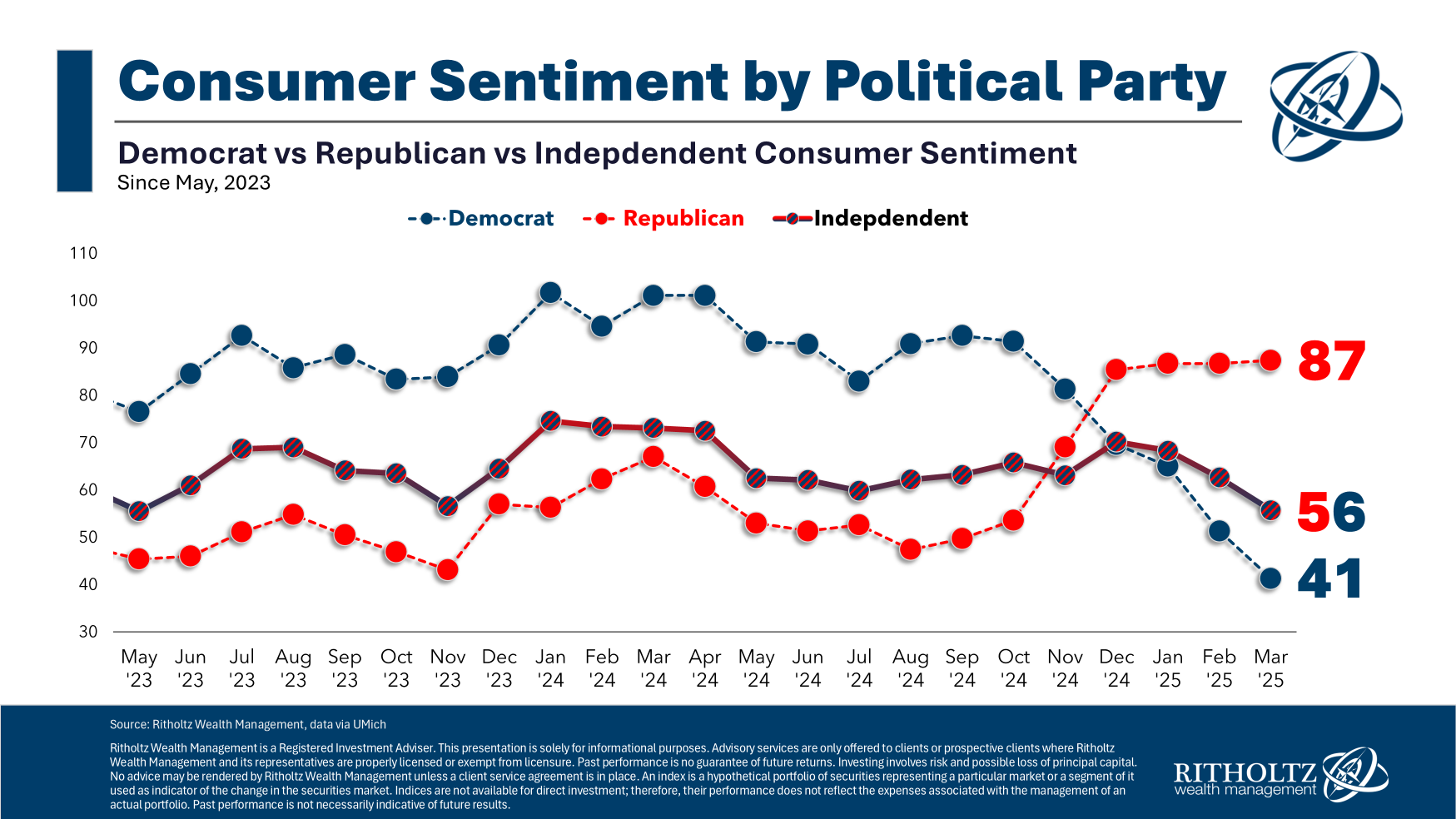

A salient feature of populism is its suspicion of experts. “That’s not how things work in the real world,” says the populist—as if experts only cared about some other world. Claims by experts are cause for suspicion, or even proof of their falsity. Populists prefer what “everyone knows” is true. The realm of truth for the populist is mediated by what is ubiquitous, which is to say, what is loudest. For the challenged expert to respond with scientific argument is almost to miss the point. It’s not that their arguments are unconvincing—they’re just not “common sense.”

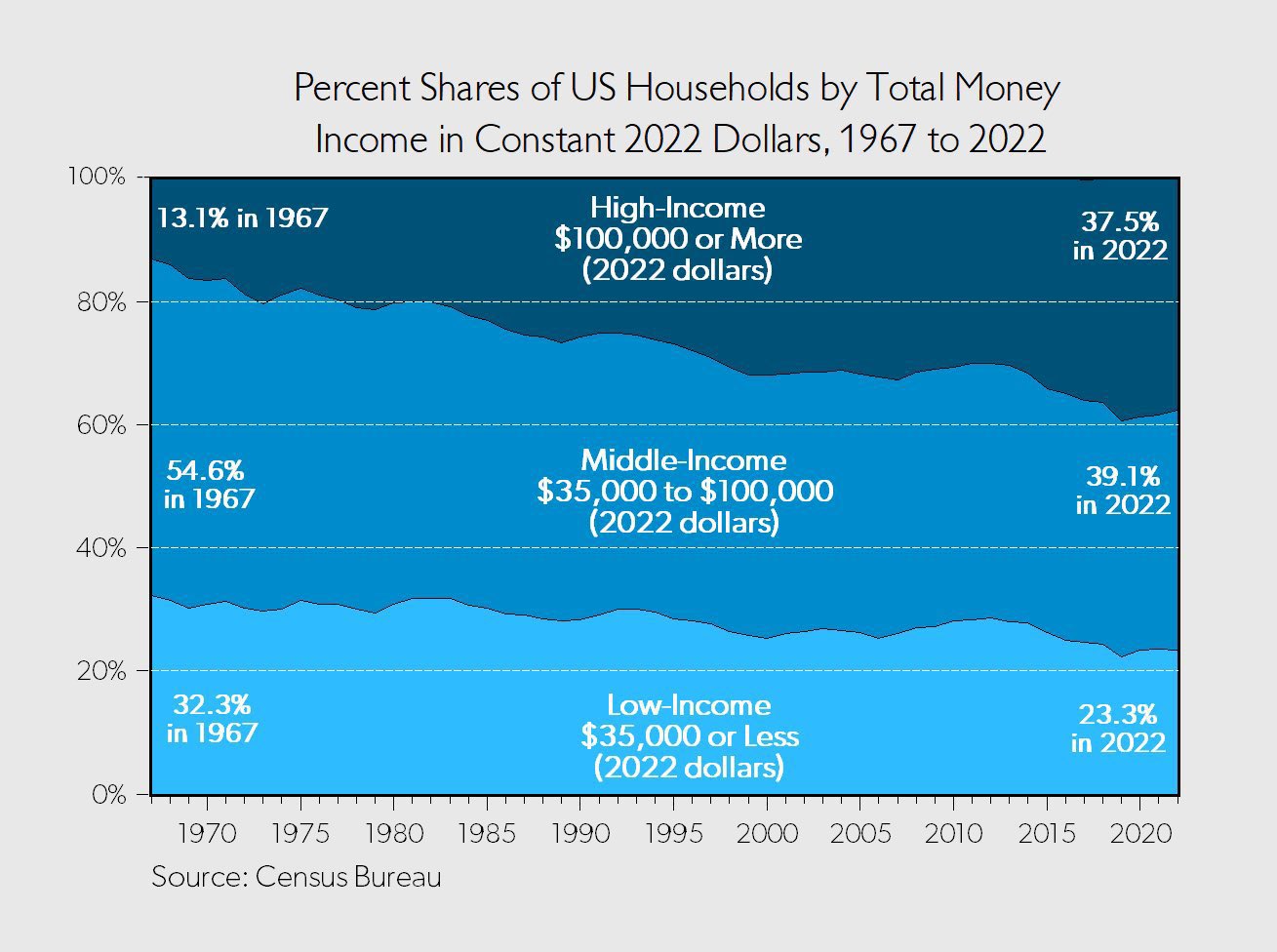

Under President Trump, it has become “common sense” that other countries are “taking advantage” of the United States, selling Americans lots of goods without buying an equal amount in return. We recently pointed out why this is a misconception. For the last 50 years, Americans have bought goods from the rest of the world with an almost unlimited line of credit extended by those same countries. This feature, which rests on the United States’ deep capital markets and internationalized currency, has long been recognized as an “exorbitant privilege.”

When announcing new tariffs, Trump offered the rest of the world a “common sense” route to avoid tariffs—just build in the United States. This, too, is a misconception.

Countries trade with each other for two basic reasons. One reason is differences in technology. Some countries are simply better at making certain products. They specialize in a few things rather than produce everything on their own, because resources are more productively invested according to their technological advantages. Then they trade their specialties with the rest of the world so they can buy everything else they don’t make.

The other big reason is differences in inputs to production. Countries differ in their endowments of human capital, physical capital, and land. Moving workers around internationally is difficult, moving factories and equipment is harder, and moving land is impossible. But you can make labor-intensive products where labor is abundant—similarly for capital and land—and then trade the products.

The real-world pattern of U.S. trade deficits matches these explanations well. The United States is good at financing investment and educating young people. The Italians are good at making supercars. It’s not that Americans and Italians aren’t good at other things, too—they’re just so much better at these things that they sell their specialties to the rest of the world and use the proceeds to buy everything else.

Labor is much cheaper in Asia than the United States, so we buy labor-intensive products like textiles and customer service (e.g., call centers) from those trading partners. Land is abundant in Canada and Australia, so we buy their timber and livestock. We have a lot of land in the United States, too, but there is so much more human and physical capital available per square mile and per worker that we are most productive making things that depend on those endowments.

Will tariffs encourage non-U.S. firms to produce in the United States? In effect, Trump is asking non-U.S. firms to bring their technology to the United States and produce with American labor, capital, and land. Relative to a world with free trade, that foreign technology would pull American resources away from their current best use in conjunction with American technology. And once the foreign firm is paying American prices for land, capital, and labor, that technology probably won’t be the most economical way to produce. Their products will cost more, the American economy will produce less overall, and incomes will fall.

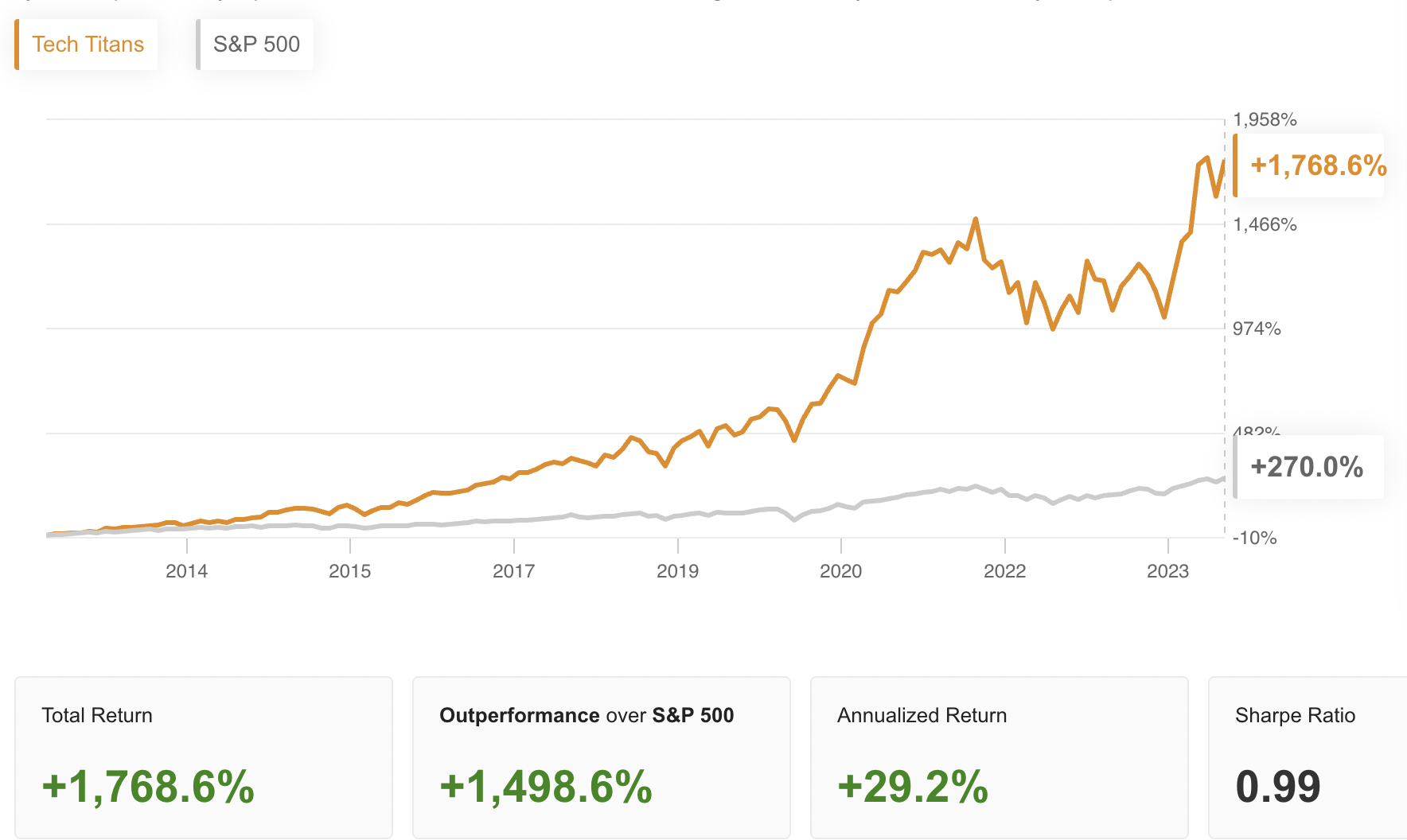

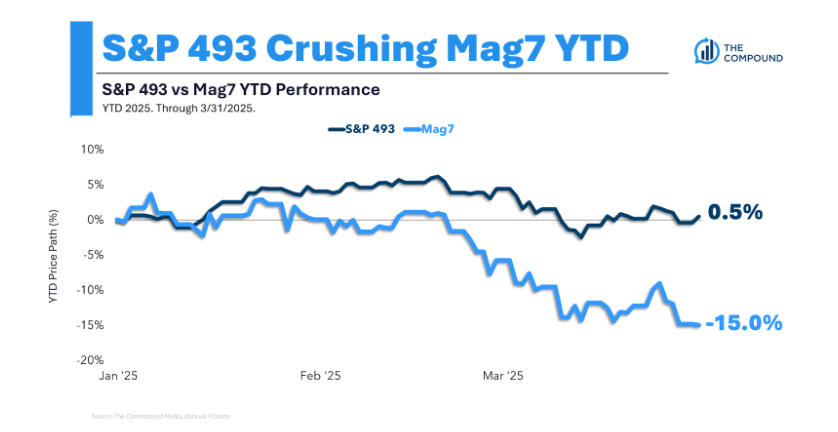

The stock market agrees with our diagnosis, even if it’s not “common sense.” Trump’s tariffs are destroying trillions in American wealth because tariffs—taxes on international transactions—destroy opportunities. Those trillions are gone from companies’ free cash flow, and they’re not coming back through higher pay for workers as the wages of populism. Though Trump has set expectations for a painful “transition period” after his new tariffs, anyone who puts themselves in a foreign firm’s shoes can understand why foreign firms won’t rush to produce in the United States.

In time, Trump will find someone else to blame for the pain he is inflicting on the country. Rather than give him the opportunity, Congress should pass new legislation taking control of tariff decisions and setting tariffs at minimal levels, or, even better, eliminating them. This is the best way to bet on America’s strengths and restore American credibility. Maybe it’s even common sense.

Matt Sekerke is a Managing Director at SEDA Experts and Senior Macro Advisor at Hiddenite Capital Partners. Steve H. Hanke is a Professor of Applied Economics at The Johns Hopkins University. They are the co-authors of Making Money Work (forthcoming, Wiley, 2025).

Read more:

- Trump’s tariffs program is based on flawed assumptions about the trade deficit

- Trump is a drunk driver taking the economy off the cliff into a needless recession—as we warned

- Trump is knowingly steering the economy off the cliff with tariffs

- Tariffs won’t make America great again: Export-Import Bank’s former chairman and president

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com