Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ leaves the world trading system without a leader: ‘The era of rules-based globalization and free trade is over’

For decades, the U.S. was at the center of the rules-based trading system, thanks to the WTO and its massive consumer market. No longer.

It’s a real trade war now.

Beijing responded to Donald Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs on Friday, slapping its own 34% tariffs on all U.S. imports, matching the new so-called reciprocal tax rate imposed by the U.S. president on Wednesday. The tariffs come into effect on April 10, one day after Trump’s tariffs.

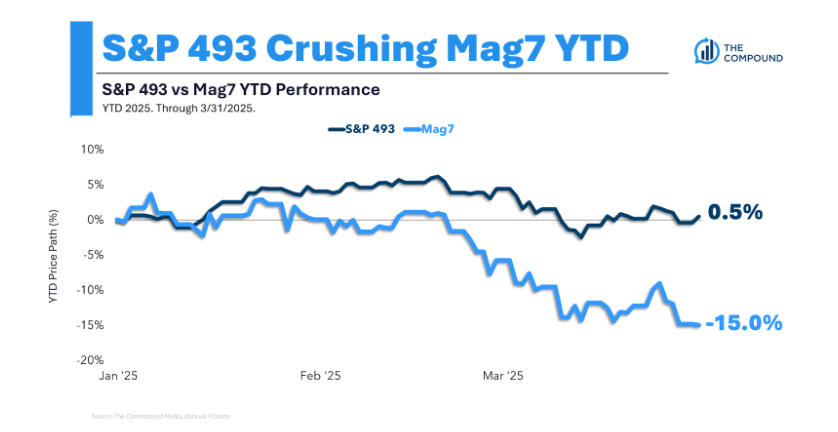

The news shook an already spooked U.S. market, sending the S&P 500 almost 6% lower on Friday. Boeing—which once supplied a third of its 737 planes to China—dropped by over 9%. U.S.-listed Chinese companies also performed poorly, with the NASDAQ Golden Dragon China Index dropping by around 9%.

The collapse in U.S. markets followed continued declines in Asia, which bore the brunt of Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs. Japan’s benchmark Nikkei 225 index is now down by 5.2% in the two trading days since April 2. South Korea’s KOSPI is down by 1.6% over the same period. India’s NIFTY 50 fell by 1.8%. (Perhaps fortunately, Chinese markets, including in Hong Kong, were closed for Qingming Festival, or “Tomb Sweeping Day”)

Yet beyond the market reactions, China’s retaliation raises the possibility that Trump’s tariffs—despite the claims by his supporters that countries would either adjust to the new taxes, or hurry to the negotiating table to offer concessions—will send the world into an extended period of protectionism.

“Rather than fixing the rules that some U.S. trading partners took advantage of to their own benefit, Trump has chosen to blow up the system governing international trade,” Eswar Prasad, senior professor of trade policy at Cornell University, says. “He has taken the hatchet to trade with practically every major U.S. trading partner, sparing few allies or rivals.”

And now, the world faces a trading system without a clear leader. Some countries will try to offer concessions to the U.S., others will try to build new trading links with other economies—and some are now seeing an opportunity to leverage relatively lower tariff rates to take market share from competitors.

"The era of rules-based globalization and free trade is over. We're entering a new phase, one that is more arbitrary, protectionist, and dangerous," Singapore Prime Minister Lawrence Wong said in a video statement released Friday.

"Global institutions are getting weaker; international norms are eroding. More and more countries will act based on narrow self-interest and use force or pressure to get their way."

How bad an effect will tariffs have?

The Trump administration imposed broad tariffs, often far above the 10% baseline, across the Asia-Pacific region. Southeast Asia was hardest hit, with Cambodia and Vietnam getting 49% and 46% tariffs respectively. China got a 34% tariff, on top of previously announced 20% tariffs. Other East Asian economies, like South Korea, Taiwan and Japan, got tariffs of between 24% to 32%. Only a handful in the Asia-Pacific—Australia, New Zealand, and Singapore—got the 10% baseline.

Goldman Sachs on Thursday downgraded GDP forecasts across Asia-Pacific, with Vietnam getting the biggest hit, dropping to 5.6%, a full 1.5 percentage points lower than its previous projection. Taiwan, which got a 32% tariff, also took a big hit in the bank’s forecasts, dropping a percentage point down to 1.6%.

HSBC estimated that 54% tariffs on China—the current level imposed by Trump—could drag China’s GDP growth down by 1.5 percentage points, down from its earlier projection of 4.8%.

Analysts don’t expect other Asia-Pacific countries to copy China in trying to counter Trump’s tariffs.

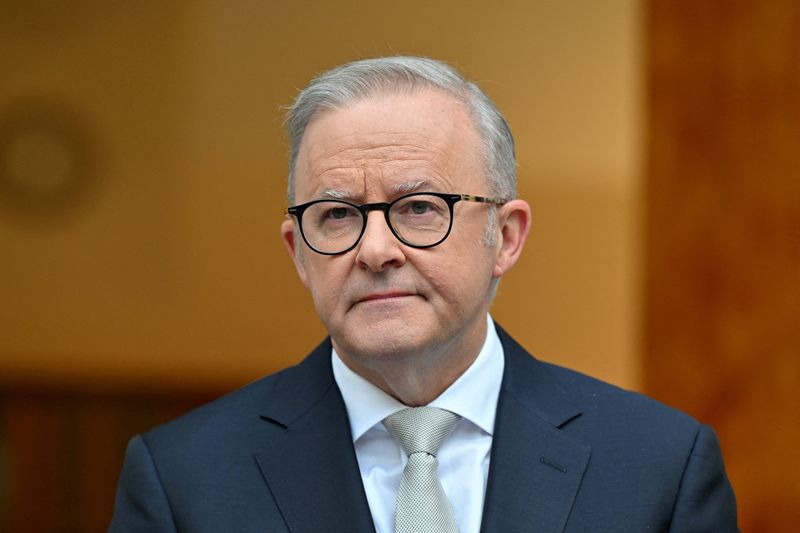

“Most other countries will resist the urge to escalate,” says James Laurenceson, director of the Australia-China Relations Institute at the University of Technology Sydney. “Most countries in Asia remain of the view that open trade is good for prosperity and also security.”

He adds that “the mood in Australia is one of disappointment, but if the U.S. wants to engage in self-harm, the best strategy isn’t to respond by engaging in self-harm too.” (Australia has said it won’t retaliate to Trump’s new 10% tariff).

“South Korea will likely offer more concessions,” such as participating in gas projects in Alaska or buying more U.S. agricultural products, suggests Ramon Pacheco Pardo, an international relations expert and Korea expert at King’s College London.

On Friday, U.S. President Trump claimed that Vietnamese officials had offered to “cut their tariffs down to zero.” The Southeast Asian countries had previously offered to cut duties on U.S. imports. Cambodia has also offered to cut tariffs on a range of imports to 5%, according to local outlet The Khmer Times.

Economies may also offer domestic support, like Taiwan’s announcement of $2.7 billion in aid for local manufacturers hurt by Trump tariffs.

But the U.S. probably won't be able to restore itself to economic primacy in the region, suggests Van Jackson, a senior lecturer in international relations at Victoria University of Wellington and author of The Rivalry Peril: How Great-Power Competition Threatens Peace and Weakens Democracy. "The U.S. has gradually alienated itself from Asian economic realities. America, in other words, doesn't have the cards to do what it's trying to do," he says.

What happens when no one is leading trade?

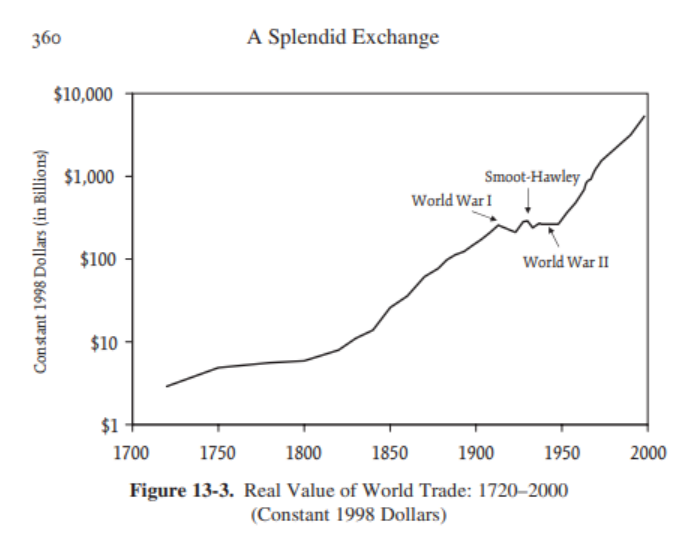

For decades, the U.S. was at the center of the so-called rules-based trading system, supporting institutions like the World Trade Organization and leveraging its massive consumer market. While the U.S. commitment to free trade was never quite as strong as its rhetoric suggested, “Liberation Day”, by rocketing duties up to a level not seen since the 1930 Smoot-Hawley tariffs, has now clearly left the world trading system without a leader.

“What the U.S. is doing now is not reform. It is abandoning the entire system it had created,” Singapore’s prime minister said Friday.

That could be risky. "A world where the hegemon abandons obligations of international order maintenance and is just in pure power- and wealth-hoarding mode is a danger to itself and others," Jackson says.

Fault lines are already starting to be drawn.

The Philippines, which got a relatively lenient 17% tariff hit, sees “Liberation Day” as an opportunity to win market share from its neighbors. The Southeast Asian country is eager to boost its exports of chips, electronics and coconuts to the U.S. “We will definitely take advantage of the lower tariffs,” trade minister Cristina Roque said in a Bloomberg TV interview on Friday morning. “Now that our tariffs are lower than [competitors like Thailand], we will probably have a stronger edge."

Another possibility is that Asia builds new trading relationships, whether internally or with other developed markets in Europe or the Middle East.

“Faced with both restricted access to U.S. markets and weaker U.S. consumer demand on account of the Trump tariffs, the rest of the world will look to export market diversification, trade arrangements that exclude the United States, and other approaches to buffer themselves against a looming global trade war,” Prasad suggests.

That’s true in China, already trying to build its links with the Global South. Beijing is “encouraging more companies to go overseas” which can lead to a “strong short-term boost for exports,” says Dan Wang, a director on Eurasia Group’s China team. “As soon as you establish factories overseas, they have to import machinery to set those factories up.”

Economists have previously expressed worries about a tariff cascade in response to a potential flood of Chinese goods.

Still, Wang thinks that there won’t be a “universal pushback” to China’s goods. She suggests that “pillar industries” like autos or green energy might spur “strong pushback" from foreign governments. But in the end, “China is a major producer. It supplies goods that cannot really be replaced by another country, or even a combination of other countries.”

And Beijing may win some kudos by being a relative bastion of stability, at least compared to Trump.

“In the short term, China can reap low-hanging public relations fruit and collect easy wins by appearing stable, reliable, and simply by not doing what the U.S. is doing,” says Austin Strange, an international relations professor at the University of Hong Kong.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com