The journal Nature touts “two-eyed seeing” (the supposed advantage of combining modern scientific knowledge with indigenous “ways of knowing”)

The 1953 paper in Nature by Watson and Crick positing a structure for DNA is about one page long, while the Wilkins et al. and Franklin and Gosling papers in the same issue are about two pages each. Altogether, these five pages resulted in three Nobel Prizes (it might have been four had Franklin lived). … Continue reading The journal Nature touts “two-eyed seeing” (the supposed advantage of combining modern scientific knowledge with indigenous “ways of knowing”)

The 1953 paper in Nature by Watson and Crick positing a structure for DNA is about one page long, while the Wilkins et al. and Franklin and Gosling papers in the same issue are about two pages each. Altogether, these five pages resulted in three Nobel Prizes (it might have been four had Franklin lived).

Sadly, such concision has fallen by the way now that ideology has invaded the journal. This new paper in Nature (below), a perspective that touts the scientific advantage to neurobiology of combining indigenous knowledge with modern science—the so-called “two eyed seeing” metaphor contrived by two First Nations elders in Canada 21 years ago—is 10.25 pages long, more than twice as long as the entire set of three DNA papers. And yet it provides nothing even close to the earlier scientific advances. That’s because, as you might have guessed, indigenous North Americans do not have a science of neurobiology, or ways of looking at the field that might be helpfully combined with what we already know. What the authors tout at the outset isn’t substantiated in the rest of the paper.

Instead, the real point of the paper is that neuroscientists should treat indigenous peoples properly and ethically when involving them in neurobiological studies. In fact, the paper calls “Western” neuroscientists “settler colonialists,” which immediately tells you where this paper is coming from. Now of course you must surely behave ethically if you are doing neuroscience, towards both animals and human subjects or participants, but this paper adds nothing to that already widespread view. And it gives not a single example of how neuroscience itself has been or could be improved by incorporating indigenous perspectives.

The paper is a failure and Nature should be ashamed of wasting over ten pages—pages that could be devoted to good science—to say something that could occupy one paragraph.

Click below to read the paper, which is free with the legal Unpaywall app, or find the pdf here,

My heart is sinking as I realize that I have to discuss this “paper” after reading it twice, but let’s group its contentions under some headings (mine, though Nature‘s text is indented):

What is “two-eyed seeing”?

This Perspective focuses on the integration of traditional Indigenous views with biomedical approaches to research and care for brain and mental health, and both the breadth of knowledge and intellectual humility that can result when the two are combined. We build upon the foundational framework of Two-Eyed Seeing1 to explore approaches to sharing sacred knowledge and recognize that many dual forms exist to serve a similar beneficial purpose. We offer an approach towards understanding how neuroscience has been influenced by colonization in the past and efforts undertaken to mitigate epistemic, social and environmental injustices in the future.

The principle of Two-Eyed Seeing or Etuaptmumk was conceived by Mi’kmaq Elders, Albert and Murdena Marshall, from Unama’ki (Cape Breton), Nova Scotia, Canada, in 20041 (Fig. 1). It is considered a gift of multiple perspectives, treasured by many Indigenous Peoples, which is enabled by learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing, and from the other eye with the strengths of non-Indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing. It speaks not only to the importance of recognizing Indigenous knowledge as a distinct knowledge system alongside science, but also to the weaving of the Indigenous and Western world views. This integration has attained Canada-wide acceptance and is now widely considered an appropriate approach for researchers working with Indigenous communities.

It is, as you see, a push to incorporate indigenous “ways of knowing” into modern science—in this case neuroscience, though there’s precious little neuroscience in the paper. The paper coiuld have been written using nearly any area of science in which there are human subjects. And, in fact, we do have lots of papers about how biology, chemistry, and even physics can be improved by indigenous knowledge (“two-eyed seeing” is simply the Canadian version of that trope).

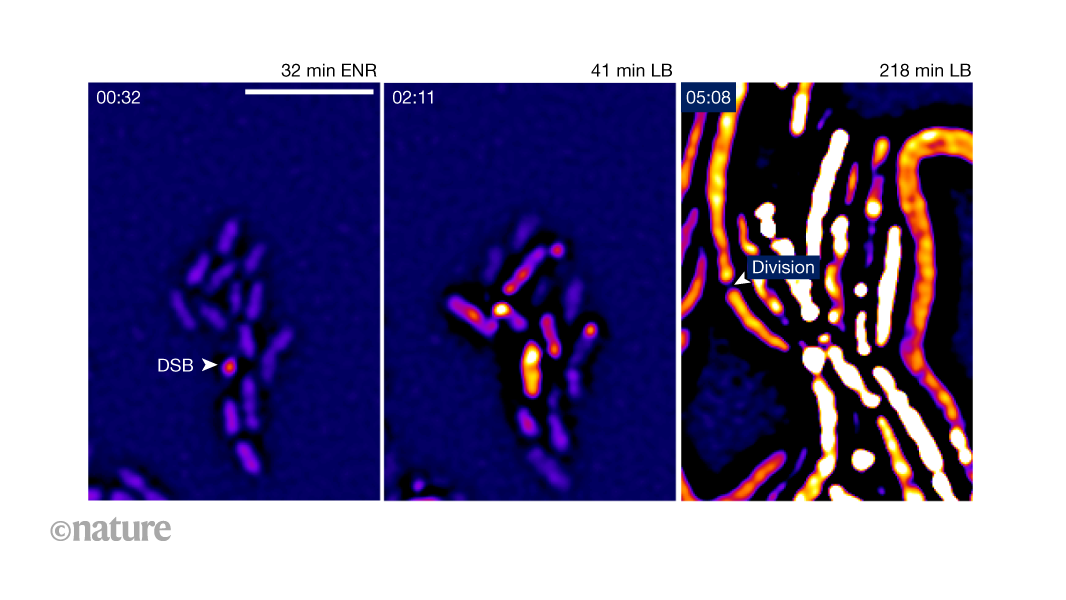

And as is so often the case in this kind of paper, there are simple and juvenile figures that don’t add anything to the text. The one blow is from the paper. Note that modern science is called “Western”, a misnomer that is almost always used, and is meant to imply that the knowledge of the “West” is woefully incomplete

Isn’t that edifying?

What is two-eyed seeing supposed to accomplish? Some quotes:

Here we argue that the integration of Indigenous perspectives and knowledge is necessary to further deepen the understanding of the brain and to ensure sustainable development of research4 and clinical practices for brain health5,6 (Table 1 and Fig. 2). We recognize that, in some parts of the world, the term Indigenous is understood differently. We are guided by the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues that identifies Indigenous people as

[…] holders of unique languages, knowledge systems and beliefs and possess invaluable knowledge of practices for the sustainable management of natural resources. They have a special relation to and use of their traditional land. Their ancestral land has a fundamental importance for their collective physical and cultural survival as peoples. Indigenous peoples hold their own diverse concepts of development, based on their traditional values, visions, needs and priorities.

. . . There are many compelling reasons for neuroscientists who study the human brain and mind to engage with other ways of knowing and pursue active allyship, and few convincing reasons to not. Fundamentally, a willingness to engage meaningfully with a range of modes of thought, world views, methods of inquiry and means of communicating knowledge is a matter of intellectual and epistemic humility11. Epistemic humility is defined as “the ability to critically reflect on our ontological commitments, beliefs and belief systems, our biases, and our assumptions, and being willing to change or modify them”12. It shares features with interdisciplinary thinking within Western academic traditions, but it stands to be even more enlightening by providing entirely new approaches to understanding. Epistemic humility is an acknowledgement that all interactions with the world, including the practice of neuroscience, are influenced by mental frameworks, experiences and both unconscious and overt biases.

“Humility” and “allyship” are always red-flag words, and they it is supposed to apply entirely to the settler-colinialist scientists, not to indigenous people.

Why is “one eyed” modern science harmful? Quotes:

Brain science has largely drawn on ontological and epistemological cultural ways of being and knowing, which are dominantly held in Western countries, such as those in North America and Europe. In cross-cultural neuroscience involving Indigenous people and communities, both epistemic and cultural humility call for an understanding of the history of colonialism, discrimination, injustice and harm caused under a false umbrella of science; critical examination of the origins of current and emerging scientific assessments; and consideration of the way culture shapes engagement between Western and Indigenous research, as well as care systems for brain and mental health.

. . . Why, then, is such engagement with Indigenous ways of knowing not more widespread in human neuroscience research and care? There would seem to be a litany of reasons: ongoing oppression and marginalization of Indigenous peoples in many societies and scientific communities, individual and systemic epistemic arrogance in which only the Western way of knowing is perceived to be of value, lack of knowledge of other knowledge systems, lack of relationships with Indigenous partners that has been fuelled in part by the exclusion and marginalization of Indigenous scholars in academia, challenges to identifying ways of decolonizing or Indigenizing a particular area of study and fear of consequences for making mistakes or causing offence9,15, among others.

. . . Given existing power imbalances, Western knowledge largely dominates the world in which Indigenous peoples reside and, as a result, there is often no choice as to whether to engage with it. In contrast, non-Indigenous peoples have the privilege to choose whether to engage with Indigenous knowledge systems. Although significant learning about Indigenous knowledge systems for settler colonialists remains, full reciprocity is not necessarily a requirement.

Here we see the singling out of power imbalances, the emphasis on colonialism, and the supposed denigration of valuable “indigenous knowledge systems” (which aren’t defined)—all of which are part of Critical Social Justice ideology. But note the first sentence above: the implication that “two-eyed seeing” is supposed to actually improve brain science itself.

On neuroethics. In fact, the authors give no examples where it does that. Instead, the concentration of the paper is on “neuroethics”. I talked to my colleague Peggy Mason, a neuroscientist here, about neuroethics, and she told me that it comes in two forms. The first one, which Peggy finds more interesting, is looking at ethical questions through the lens of neuroscience. One example is determinism, and in Robert Sapolsky’s new book Determined you can see how he uses neuroscience to arrive at his deterministic conclusions and their ethical implications.

The other form of neuroethics is the one used in this paper: how to ethically deal with animals and people used in neuroscience studies. These are, in effect, “reserach ethics”, and have been a subject of discussion in recent decades. As the paper shows above, the real “revolution” in neuroscience touted in the title is simply the realization by those pesky settler-eolonialist neuroscientists that they must exercise sensitivity and empathy towards indigenous people (the implication is that they are uncomprehending and patronizing).

The next section shows the scientific vacuity of melding two types of knowledge: the real “two-eyed seeing” objective.

How has two-eyed seeing improved our understanding of neuroscience? No convincing examples are given in the paper, but here are a few game tries:

Historically, Indigenous peoples have been largely excluded from brain and mental health science, or included but never benefited from the scientific advancements. There are also ample examples, in the brain and mental health sciences and elsewhere, in which the cultural beliefs of Indigenous peoples were patently disrespected. A distinct example is the Havasupai Tribe case, where scientists at Arizona State University in the USA used blood samples they had collected from the Havasupai people to conduct unconsented research on schizophrenia, inbreeding and human population migration20. The Havasupai people, who have strong beliefs about blood and its relation to their sense of identity, spiritual connection and cultural cohesion, were advised that the blood samples were being collected for purposes of conducting diabetes research. The community filed two lawsuits against the university upon learning about the misuse of their blood samples for research questions they do not support.

In another stark example, results from an international genomics study on the genetic structure of ‘Indigenous peoples’ [sic] recruited in Namibia21 were compared to results of a study of the ‘Bantu-speaking people of southern Africa’22,23. The Namibian people were the Indigenous San (including the!Xun, Khwe and ‡Khomani) and Khoekhoe people who include the Nama and Griqua, first to be colonized in southern Africa21. Among numerous missteps in the research, published supplementary materials contained information entirely unrelated to genomics and other information about the San that was unconsented, private, pejorative and discriminatory.

These examples of violations of research ethics in neuroscience and genomics highlight the need for Two-Eyed Seeing to ensure individual and professional scientific integrity.

Neither of these are examples of improvements in understanding neuroscience via “two-eyed seeing”. One is about the proper and ethical way to collect blood from indigenous people; the other is about genetic differences between African populations.

Can we do better? How about an example from studies of mental health?

Other successful studies among the amaXhosa people in South Africa in 2020 exemplify the embodiment of cultural humility and trust-building. Gulsuner et al.29 and Campbell et al.30 demonstrated the importance of inviting people with lived experience of a mental health condition, brain and mental health professionals, members of the criminal justice system, local hospital staff as well as traditional and faith-based healers to provide education about severe mental illness and local psychosocial support structures to promote recovery. Through co-design, implementation and evaluation, the researchers assessed the effects of the co-created mental health community engagement in enhancing understanding of schizophrenia and neuropsychiatric genomics research as it pertains to this disorder30. They collaboratively presented mental health information and research in a culturally sensitive way, both respecting the local conceptualization of mental health and guarding against the possible harms of stigma31. They incorporated cultural practices, such as song, dance and prayer, with the guidance of key community leaders and amaXhosa people that included families affected by schizophrenia, to foster a process of multidirectional enlightenment and, in effect, Two-Eyed Seeing.

Again we see the emphasis on cultural sensitivity, which of course I agree with, but whether and how this method helped us understand how to cure schizophrenia and improve “neuropsychiatric genomics research” is not explained. There may be something there, but the authors fail to tell us what.

Finally, the authors relate the sad story of Lia Lee, a severely epileptic Hmong child in California whose treatment was difficult (she was in a vegetative state for 26 of her 30 years after her last seizure), for the doctors couldn’t communicate with the parents (see here and here) . Treatment was further impeded because the Hmong parents, who really loved Lia deeply, also believed that epilepsy was a sign that she was spiritually gifted, and so were conflicted and erratic in giving her the prescribed medication. This is an example where some indigenous beliefs are harmful to treatment, just as in some cultures that mistreat people who are mentally ill because they think they are possessed by supernatural powers. Two-eyed seeing is not always good for patients! From the paper:

Epilepsy serves as a poignant example of how a dual perspective can enrich the spirituality of health and wellbeing, and where collisions with biomedicine can lead to tragic consequences. One example can be taken from the book The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down, in which author Anne Fadiman51 documents the story of Lia Lee, a Hmong child affected with Lennox–Gastaut syndrome. Lia’s parents attributed the symptoms of her seizures to the flight of her soul in response to a frightening noise—quab dab peg (the spirit catches you and you fall down; translated as epilepsy in Hmong–English dictionaries) and, although concerned, were reluctant to intervene because they viewed its symptoms as a form of spiritual giftedness. Lia’s doctors were faced with limited therapeutic choices, challenges of communication, and a general lack of cultural competence. Exacerbated by disconnects and failures of both traditional and Western healthcare, responsive options and years of effort were eclipsed in a perfect storm of mistrust and misunderstanding.

Since the 1990s when the book was written, closing gaps in health equity, reducing the marginalization of vulnerable and historically neglected populations such as Indigenous peoples and promoting individual and collective autonomy have become a focus in both neuroscience research and clinical care.

Fadiman’s book is read widely in medical schools, used to promote cultural sensitivity towards patients. That’s fine (though it couldn’t have helped Lia), but again it doesn’t help us understand neuroscience itself.

What are some of the indigenous practices said to contribute to neuroscience? Several are mentioned, but have nothing to do with neuroscience. Here’s one:

. . . ,. there remains significant potential integrating Indigenous theories around the brain and mind. For example, while the Kulin nations conceptualize distinct philosophies of yulendj (knowledge/intelligence), toombadool (learning/teaching) and Ngarnga (understanding/comprehension), views of the mind and brain tend to not be static and individualistic, but holistic, dynamic and interwoven symbiotically within the broader environment. The durndurn (brain) is not just a singular organ, but a part of the body that contains some aspects of a murrup (spirit), within the pedagogy of a broader songline.

This concept of a songline is present across many Indigenous cultures35. Although songlines can present as dreaming stories, art, song and dance, their most common use is as a mnemonic. Such is the success of using songlines in memory that it has allowed oral history to accurately survive tens of thousands of years—with accuracy often setting precedent for scientific verification. The breadth of their use would allow the common person to memorize thousands of plants, animals, insects, navigation, astronomy, laws, geological features and genealogy. Whether conceived as songlines, Native American pilgrimage trails, Inca ceques or Polynesian ceremonial roads, all use similar Indigenous methods of memorization36. This aligns with modern neuroscience findings that emphasize the capacity of the brain for complex memory processes and the role of mnemonic techniques in enhancing memory retention. Moser, Moser and O’Keefe were awarded the 2014 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for research that grounded the relationship between memory and spatial awareness when establishing that entorhinal grid cells form a positioning system as a cognitive representation of the inhabited space. Elevated hippocampal activity when utilizing spatial learning encourages strong memorization through associative attachment, and these techniques are readily used by competitive memory champions. Two-Eyed Seeing songlines for the mind and brain build capacity in facilitating a respectful implementation of traditional memorization techniques in broader contemporary settings37.

Songs and word of mouth allow indigenous people to pass knowledge along. That’s fine, except that knowledge passed on this way may get distorted. Writing—the “settler-colonialist” way of preserving knowledge—is much better and more reliable. It also allows for mathematical and statistical analysis. Again, there is nothing in the two-eyed seeing that improves neuroscience, at least nothing I can see.

There’s a lot more in this long, tedious, and tendentious paper, but I won’t bore you. I do think it would make a great pedagogical tool for neuroscience students, who can evaluate the paper’s claims at the same time as discerning the ideological slant of the paper (as well as its intellectual vacuity). We’ve come to a pretty pass when one of the world’s two best scientific journals publishes pabulum like this in the interest of sacralizing indigenous people. Yes, indigenous people can contribute knowledge (“justified true belief”) to the canons of science, but, as we’ve seen repeatedly, that knowledge is usually scanty, overblown, and largely irrelevant to modern science. But Social Justice has stuck its nose in the tent science, and papers like this are the result. . .