The Federal Reserve has bigger problem on its hands than tariffs

It may not be just tariffs and jobs that determine what the Fed does with interest rates next

To cut, or not to cut. That’s the multi-trillion-dollar question.

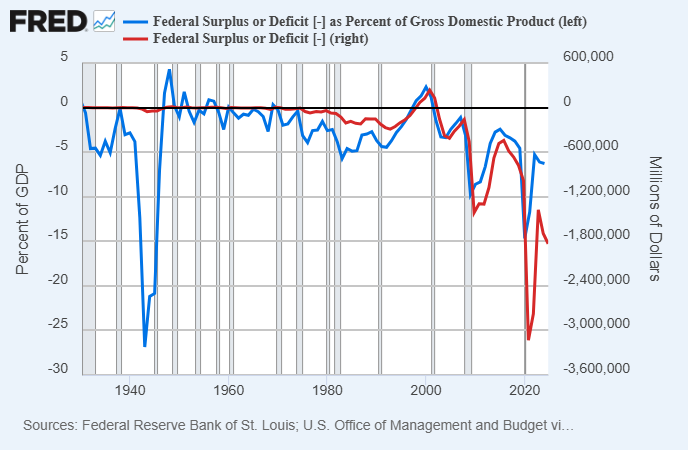

So far, the Federal Reserve has taken a conservative stance, holding interest rates steady while it awaits more clarity into the jobs market and inflation’s path in the wake of newly enacted tariffs.

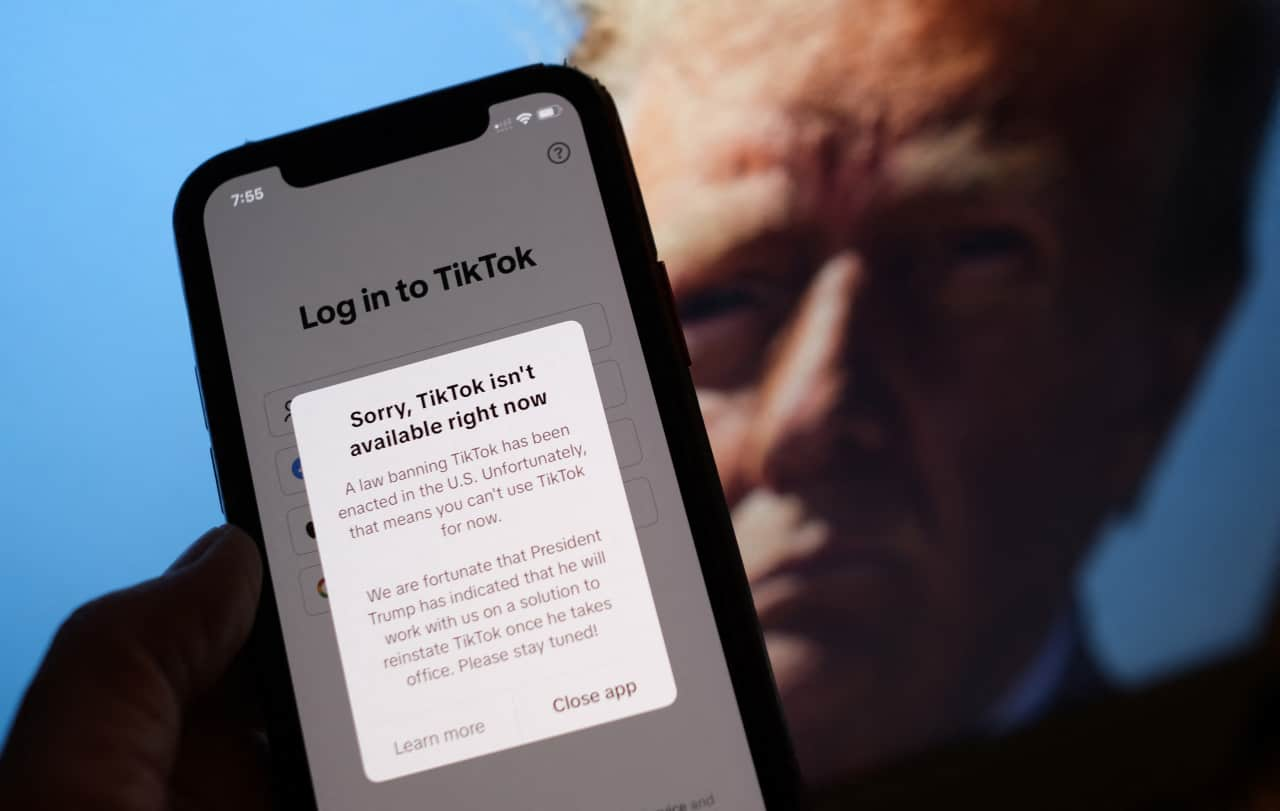

Fed chair Powell’s willingness to remain on the sidelines has drawn significant blowback from President Donald Trump, who regularly criticizes Powell for holding rates steady rather than cutting them.

Related: Fed interest rate cut decision resets forecasts for the rest of this year

However, many believe that Powell’s patience is the right policy, given massive uncertainty surrounding how tariffs may impact prices on everything from clothing to cars later this year.

The decision to raise or cut rates may not be as simple as figuring out how tariffs play out, though. Inflation may or may not spike because of them (that remains unclear), but a recent development could force the Fed’s hands, forcing it to make a decision on interest rates sooner than it wants.

The Fed risks falling behind the curve

President Trump’s disdain for Fed Chair Powell is pretty clear. So far, he’s referred to the pragmatic Powell as “Mr Too-Late,” a shot at Powell’s mistaken hesitancy to raise rates in 2021 and early 2022 to quell inflation, and a “numbskull” for not cutting interest rates yet this year.

Many expected that the Fed would be far friendlier to borrowers in 2025, given it reduced interest rates three times late last year, lowering the Fed Funds Rate by 1%.

Related: Billionaire fund manager sends strong message on Fed Chair Powell's future

The moves last year provided some relief to borrowers, particularly home buyers reeling from high mortgage rates. Many thought that ongoing cracks in employment, including rising layoffs, would mean more cuts this year.

That optimism was quickly dashed after Trump took office in January, promising to spark a return to US manufacturing by increasing tariffs.

And increase them, he did.

In February, he slapped 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico and 20% tariffs on China. Then, he upped the ante with a 10% baseline tariff on imports in April, plus 25% tariffs on autos, and, after a tariff tit-for-tat, 30% tariffs on China.

The news has sent shockwaves through markets and retailers, many of which pulled forward imports to get in front of tariffs, are warning that prices will increase once that inventory has been sold.

The risk of higher prices has trapped the Fed. Its dual mandate is to lower prices and unemployment. Unfortunately, that’s easier said than done. Raising rates lowers inflation but increases unemployment. The opposite is true when you cut rates.

Uncertain over what tent pole it should concentrate on, the Fed has chosen a wait-and-see approach even as layoffs climb. Over 696,000 workers have been laid off this year through May, according to Challenger, Gray, & Christmas, up 80% year over year.

A new ugly inflation risk rears its head

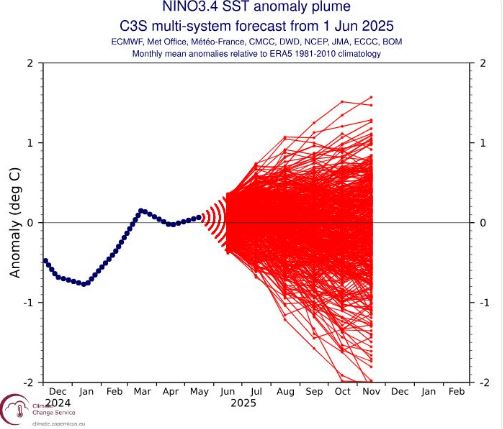

While tariffs' impact on inflation receives most of the attention, the recent war in the Middle East may determine the Fed’s next move.

Related: Bank of America unveils surprising Fed interest rate forecast for 2026

Israel’s attack and Iran’s response have raised significant concerns that global oil markets could suffer a shock if the conflict spills over, impacting oil tankers traveling through the Strait of Hormuz.

The Strait of Hormuz sees traffic of 18 million to 19 million barrels of oil daily, representing 20% of global oil consumption, including crude, condensates, and fuel. Its location off Iran means it could be a critical oil chokepoint if Iran decides to block it.

It appears that possibility isn’t off the table, despite the fact that it would significantly hurt Iran’s oil exports, which are solely sea-borne.

Closing the Strait is "under serious consideration,” said Esmail Kosari, an Iranian parliament member and IRGC general, on June 15.

The risk that the oil spigot through the Strait of Hormuz gets shut off has already caused a massive rally in crude oil prices. Brent crude and West Texas Intermediate crude oil have seen prices jump 22% and 26% this month, including an 11% increase each over the past five days amid new tensions with the United States.

President Trump seemingly appeared to want to distance the US involvement in Israel’s attacks on Iran early on, favoring negotiations. However, his stance seems to have pivoted, given he’s called for Iran’s unconditional surrender and left US involvement in destroying Iran’s nuclear facilities as a possibility.

More Federal Reserve:

- Fed interest rate cut decision resets forecasts for the rest of this year

- Federal Reserve prepares strong message on long-term interest rates

- Fed official revamps interest-rate cut forecast for this year

The full impact on gasoline prices in the US won’t be immediately felt, but we are already seeing increases. According to the EIA, weekly gasoline prices were $3.14 per gallon nationwide on June 16, up from $3.11 on June 9.

The feet-on-the-ground prices for gasoline are higher, though.

“National average price of gasoline has shot up to $3.19/gal this morning according to GasBuddy data, 7.2c higher than a week ago,” wrote GasBuddy’s Patrick DeHaan on X. “We'll likely climb to $3.25-$3.40/gal, wiping out a good portion of the [year over year] YoY drop.”

Energy, including fuels, services, and things like electricity, represents about 9.5% of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation measure. Gasoline accounts for 3%, which may not sound like much, but can move the needle (which is why economists often consider inflation ex-fuel a better gauge because of oil price volatility).

Over the past year, a drop in gasoline prices has helped keep inflation in check, with the BLS writing in its latest CPI report, “The energy index decreased 3.5 percent over the past 12 months. The gasoline index fell 12.0 percent over this 12-month span, and the fuel oil index fell 8.6 percent over the same period.”

If oil prices remain elevated (they normally rise in summer because of travel demand and the switchover to pricier summer grade gasoline, which contains less cheap butane because of smog restrictions), it could crimp retail spending and increase energy costs for manufacturers and shippers. That would pressure the $30.5 trillion US economy, potentially causing stagflation or recession.

In those scenarios, the Fed may have little option but to cut rates to prevent a spike in unemployment.

Related: Veteran fund manager who predicted April rally updates S&P 500 forecast