Netflix’s Mo Is the All-American Palestinian-Refugee Comedy Everyone Should Watch

The second season of Mo Amer's Palestinian-refugee series takes darker turns without abandoning its absurd humor or glimpses of beauty

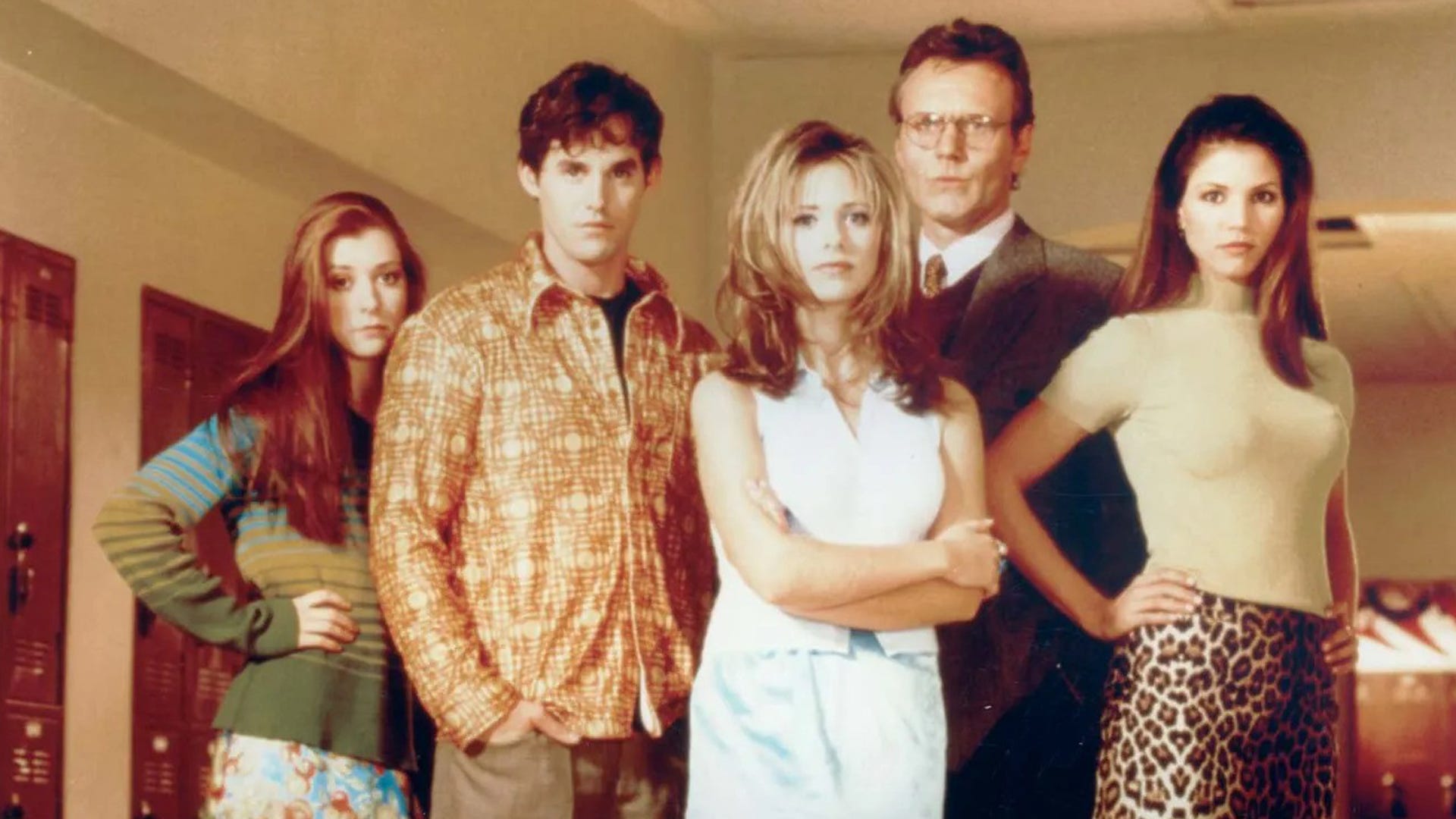

Mo Najjar lives in Houston. Manifested in a wardrobe heavy on Astros merch, his hometown pride is unmistakable. After growing up fast in the wake of his father’s death, he’s spent his adult life acting as man of the house to his loving mom, Yusra (Farah Bsieso), and autistic brother, Sameer (Omar Elba). But he has trouble holding down a job. Grazed in a mass shooting but uninsured, he gets his wound sewn up by a tattoo artist (Michael Y. Kim); the injury leaves him addicted to lean. His girlfriend, Maria (Teresa Ruiz), is impatient for a proposal, though Yusra objects to what would be an interfaith marriage. As his pals Nick (Tobe Nwigwe) and Hameed (Moayad Alnefaie) move forward in life, Mo remains stuck in survival mode. [time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

He is, in many ways, a typical American millennial—caught in two decades’ worth of economic headwinds, struggling to gain a foothold. The thing is, Mo isn’t officially an American. Palestinian refugees who fled their adoptive home of Kuwait during the Gulf War, the Najjars have been living in Texas since he was a kid, awaiting the resolution of a Kafkaesque asylum case that has stretched out for more than 20 years. At the heart of Mo, a semi-autobiographical Netflix dramedy from co-creator and star Mo Amer, is the tension between Mo the regular guy and Mo the stateless survivor, a man of estimable charms and abilities who is legally prohibited from establishing a legitimate career. The show’s recently released second and, sadly, final season raises the stakes of his misadventures, taking darker turns but abandoning neither the absurd humor nor the glimpses of beauty that add dimensions to Amer’s quintessentially American, Palestinian-refugee story.

When we last saw Mo, at the end of a debut season from 2022, he was stuck in Mexico after a scheme to recover olive trees stolen from the farm where he worked went awry, leaving him and Nick locked in the back of a truck bound for the border. While Nick’s American passport afforded him easy passage home, Mo’s liminal immigration status not only complicated his return to Houston but jeopardized his asylum case. In a season that opens just months after that finale, he’s still in Mexico City, eking out a living with a falafel taco cart by day and a luchador gig at night, estranged from Maria (but not her two Mexican aunts, who helped him get settled), and about to miss the hearing that could make the Najjars legal permanent residents of the U.S.

Mo’s south-of-the-border sojourn is, at once, a madcap crime caper—his desperation to get home yields a hilarious encounter with a diplomat’s lusty wife—and an inspired means of connecting his rarely told immigrant story with the more familiar ordeals of undocumented people crossing over from Mexico. He ends up in immigration detention, an immersion in human misery that Mo, who grew up gorging on American pop culture, filters through the carceral melodrama of The Shawshank Redemption. Amer, who created the series with Ramy auteur Ramy Youssef, spends enough time in this hellish place to make his point about its pointless cruelty but moves on before the new season of Mo becomes an unmitigated downer. Whether he’s cutting up with his lifelong buddies or bemoaning the odor of an overcrowded detention cell, Mo’s humor and hustle are the constants that maintain the show’s tone.

The funniest as well as the most eloquent episodes come in the second half of the season, when the ensemble is back together. Maria is, by now, dating an Israeli Zionist chef (Simon Rex) whose trendy restaurant plunders “Mediterranean” foodways—Mo’s worst nightmare. He, in turn, allows himself to get sucked into a relationship with Hameed’s seemingly perfect sister-in-law, Austin (Johanna Braddy), a Texas blonde eager to lock down her new man. Both the broad comedy of romantic rivalry and the gallows humor of immigration-system bureaucracy are tempered by moments of community and transcendence. Food, particularly Palestinian food, is a panacea for the Najjars; the way the camera lingers on herb-strewn rice dishes and bowls of homemade hummus, you understand why. Yusra turns her passion for making olive oil into a business. In the series’ lovely final pair of episodes, the Najjars and friends are reunited over splendid spreads; Thanksgiving is a feast of barbecued turkey, Middle Eastern dishes, and Maria’s tamales, devoured amid convivial conversation at an outdoor banquet table on the olive farm.

The owner of the farm, Buddy (Walt Roberts) is one of Mo’s several unlikely allies—an older white guy with a trucker hat and a Southern accent who becomes close with the whole family after Mo strikes a deal to let Yusra and Sameer bottle their oil on his property. In Season 1, Mo fired the Najjars’ distracted Palestinian immigration lawyer and replaced her with a more diligent attorney, Lizzie Horowitz (Lee Eddy), who happens to be Jewish. Another Jewish guy, Aba (Alan Rosenberg), hangs around the local hookah lounge, debating geopolitics and culinary customs with his Muslim friends. “We just suck as a human race,” Mo commiserates with the Indigenous man whose theft of Buddy’s trees turns out to be an attempt to right a historic wrong. But Mo’s view of human nature, while never naively optimistic, is more generous than that comment suggests. Race, religion, ethnicity—none of this makes a person good or bad. The variable is how we treat others. People are people: the same in aggregate but each an individual.

Which is not to say that Mo avoids the politics behind the Najjars’ exile. On the contrary, Mo and his family are always grappling with the consequences of the occupation, or contending with people’s prejudices against Palestinians and Muslims. Yusra can’t stop reading bad news from her homeland. Yet Season 2 ends before Hamas’ Oct. 7, 2023 massacre and the 15-month Israeli onslaught that devastated Gaza in its aftermath. It was a decision made not out of cowardice, but out of fidelity to the series’ voice. When the writers’ room tried to address the war, Amer told Vulture, “Every scene became really didactic, and this wasn’t the show.” Sanctimony would have been incompatible with Mo’s self-deprecating humor and slice-of-life scope. Even as it cracks us up, it activates our empathy for Palestinians, refugees, immigrants, and others too often erased and dehumanized. Through Amer’s eyes, we see that these communities are America, and cutting them out would tear holes in the fabric of our society.