Kiss of the Spider Woman review: Jennifer Lopez dazzles, but is that enough?

Bill Condon adapts "Kiss of the Spider Woman," starring Diego Luna and Tonatiuh. Review.

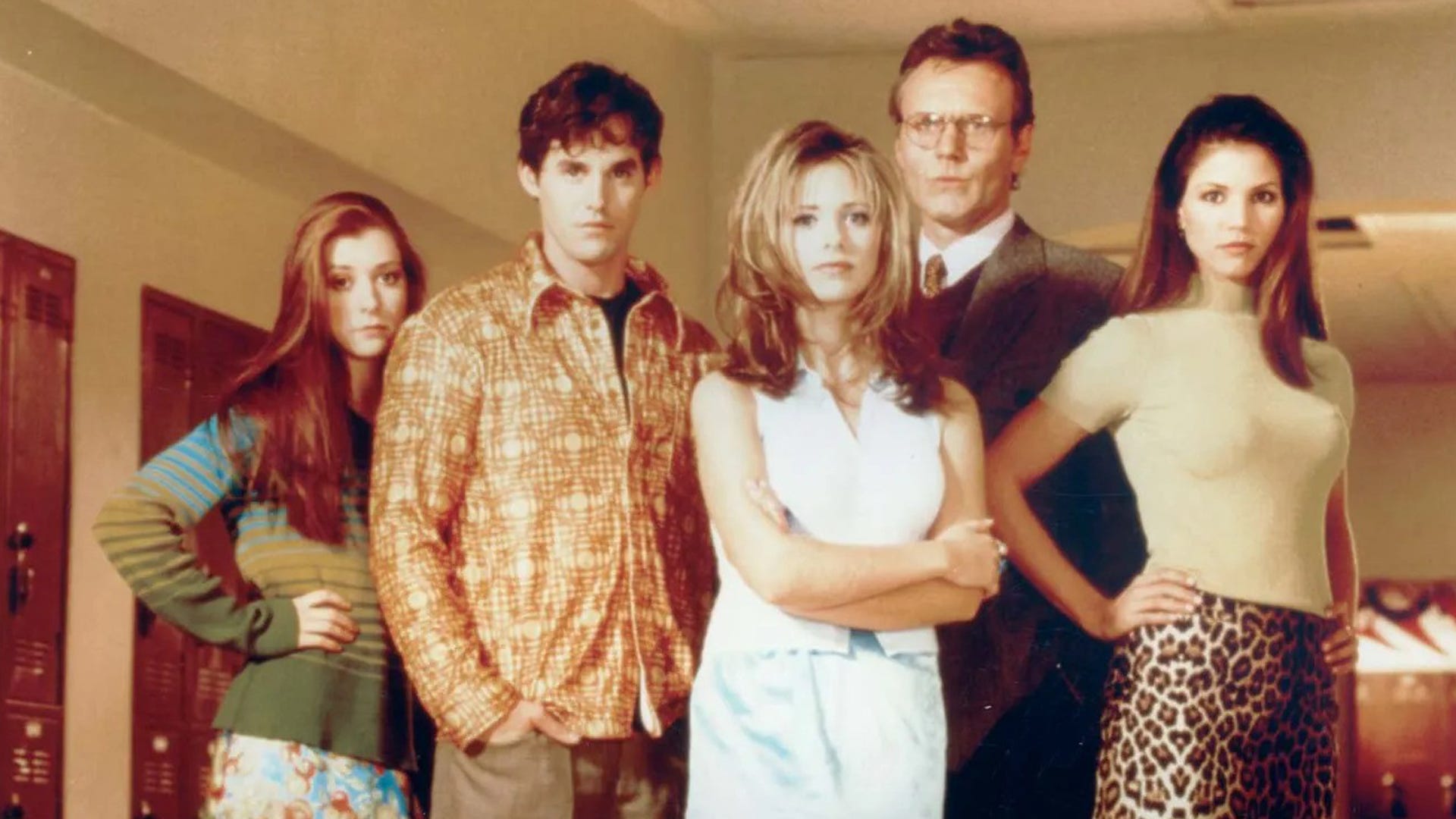

Kiss of the Spider Woman has a rich and varied history, from Manuel Puig’s 1976 novel to the 1985 Oscar-winning drama by Héctor Babenco to the 1992 stage show on which this latest film is based. This makes viewing it in isolation nearly impossible, but even on its own terms, the 2025 musical movie by Bill Condon is a difficult sell.

Set during the latter years of Brazil’s late-twentieth century military junta, it’s a tale of two wildly different prisoners and the escapist cinema they collectively imagine. The story is ripe for visual re-invention — or at the very least, visual panache. And while Condon’s version aims for something grandiose (while featuring updated sexual politics), its execution fails to capture the imagination, let alone anything resembling time and place.

What is Kiss of the Spider Woman about?

The film begins when an imprisoned Marxist revolutionary, Valentin Arregui (Diego Luna), is introduced to his new cellmate, Luis Molina (Tonatiuh), a queer and distinctly apolitical hairdresser arrested for public indecency. Condon’s film makes it much more explicit than in other versions — which is to say, through more direct dialogue — that Molina is a trans woman, even though she may not have the right terms to label herself in the movie’s 1981 setting.

Whatever qualms Arregui might have about Molina’s identity fade rather quickly, which allows the duo to quickly become friends, despite their opposing natures. Arregui is a quiet, studious learner, while Molina is a gossip and a chatterbox. However, the former becomes entranced by Molina’s stories about Technicolor Hollywood musicals, especially one titled Kiss of the Spider Woman starring her favorite Latin American starlet, Ingrid Luna (Jennifer Lopez). As Molina narrates the film to Arregui, the two picture themselves as supporting characters in its plot, while Condon cuts back and forth between this imagined cinematic landscape and the more dour prison reality they share.

Molina has also been conscripted as a snitch by the prison’s warden, who forces her to inform on Arregui if she wants to get out and see her mother again, though the duo’s growing closeness makes her question this commitment. This broad plot is not unlike all other versions of the story (with some minor deviations: both films are set in Brazil, while the book and the stage show unfold in Argentina), but the major difference is how central and self-reflexive the very idea of musicals is to the duo’s retellings.

Kiss of the Spider Woman is a musical about musicals.

Arregui, a grump and an academic, thinks of musicals as distracting propaganda and an opiate of the masses, while Molina finds beauty and acceptance in them. It’s a simple setup that should, in theory, bring the two characters closer together as Arregui grows more intrigued. However, the film’s Arabian Nights by way of Busby Berkeley telling unfolds in unconvincing ways.

The more Arregui complains about the fantastical nature of musicals (especially the escapism of people bursting out in song), the more Kiss of the Spider Woman ought to counter his assertions with examples of the opposite, but its form is never self-evident enough to be convincing. Instead, during its musical numbers, its frame is too crowded to draw the eye — rarely does Condon use blocking either to tell the story, or to deliver maximum impact — and the film lacks the energy of the golden age Hollywood landmarks it attempts to ape.

This lethargic use of visual form cross-pollinates between the real and the imagined. On one hand, Lopez’s Luna is a dazzling presence, but she seldom elevates Kiss of the Spider Woman beyond its impressions of other movies. Back in the real world, Arregui and Molina’s cramped cell certainly makes for a downtrodden setting, but Condon rarely films it with a sense of space in mind. Tonatiuh is just as impressive as Lopez, but their attempts to imbue their character with a sense of physical struggle, within four walls inching ever closer, is often undone by a haphazard edit.

Something both classical Hollywood musicals and Babenco’s version have over Condon’s version is their use of wide shots, and two-shots, meant to capture actors’ evolving relationships to one another. A major problem with the 2025 movie is that its actors rarely feel as if they’re playing in the same space, so their relationship lands only logistically — as dictated by their dialogue, when they state how they feel about one another — rather than emotionally. This is where it becomes especially hard not to compare this latest iteration to previous versions.

Kiss of the Spider Woman fails where other versions succeeded.

The gender politics of Babenco’s film certainly haven’t aged well — few mainstream films from the 1980s do when it comes to trans representation — but it had an emotional authenticity Condon’s version lacks. While William Hurt’s version of Molina was more caricatured on the surface, the writing and editing also allowed his performance more breathing room, resulting in tremendous dramatic depth. Tonatiuh is just as showy (the way a musical-loving character like Molina ought to be), with panther-like movements that create a sense of physical intrigue. And while their baseline harbors a tug-of-war between optimism and uncertainty, this dilemma is something the film’s construction rarely allows them to access. The editing renders their performance too extreme, with its zero-to-sixty gesticulations and emoting. It has a starting point and an ending point, but rarely does it have a path.

These extreme bookends also guided Hurt and co-star Raul Julia, who played a more reserved, more simmering Arregui, but their journey from one end to the other was the entire crux of Babenco’s film. Theirs was a much more rocky relationship, even though we were dropped into it in medias res. While a more bigoted Arregui might make for a less pleasant viewing experience — especially in an escapist musical — Julia’s incarnation results in complex layers to the character being gradually unearthed. Luna, while fine in the same role, is shouldered with something far less rigorous and remarkable, as a man whose inward and outward discomforts are quickly brushed under the rug.

The duo becoming comrades so quickly not only robs the story of its sense of discovery, but also prevents the 2025 film from accessing a fundamental aspect of Puig’s novel. The author’s formal experimentation meant that both characters’ dialogue was presented free from delineation or attribution, separated only by dashes, leaving you to decipher who’s speaking from context clues. They feel, at times, like one and the same person. Babenco’s drama captures the spirit of this flourish by telling a story of two souls gradually becoming one..

In contrast, any hint of romance in the new Kiss of the Spider Woman is dulled and distant, and its sense of optimism has few ugly depths that allow it to stand out through greater contrast. Forty years after Babenco’s film, Condon’s musical may be more palatable and progressive, but his versions of Molina and Arregui never feel like halves of a whole, leaving the movie feeling emotionally incomplete.

Kiss of the Spider Woman was reviewed out of the 2025 Sundance Film Festival.