If Chemical Weapons Return, We’re All in Danger – Here’s Why

Although chemical weapons are technically and legally not allowed to be used in combat scenarios, several countries have or may attempt to do so should they believe they could get away with it. This would cause severe harm to the troops facing said weapons. But a research team from Washington University in St. Louis (WashU) […] The post If Chemical Weapons Return, We’re All in Danger – Here’s Why appeared first on 24/7 Wall St..

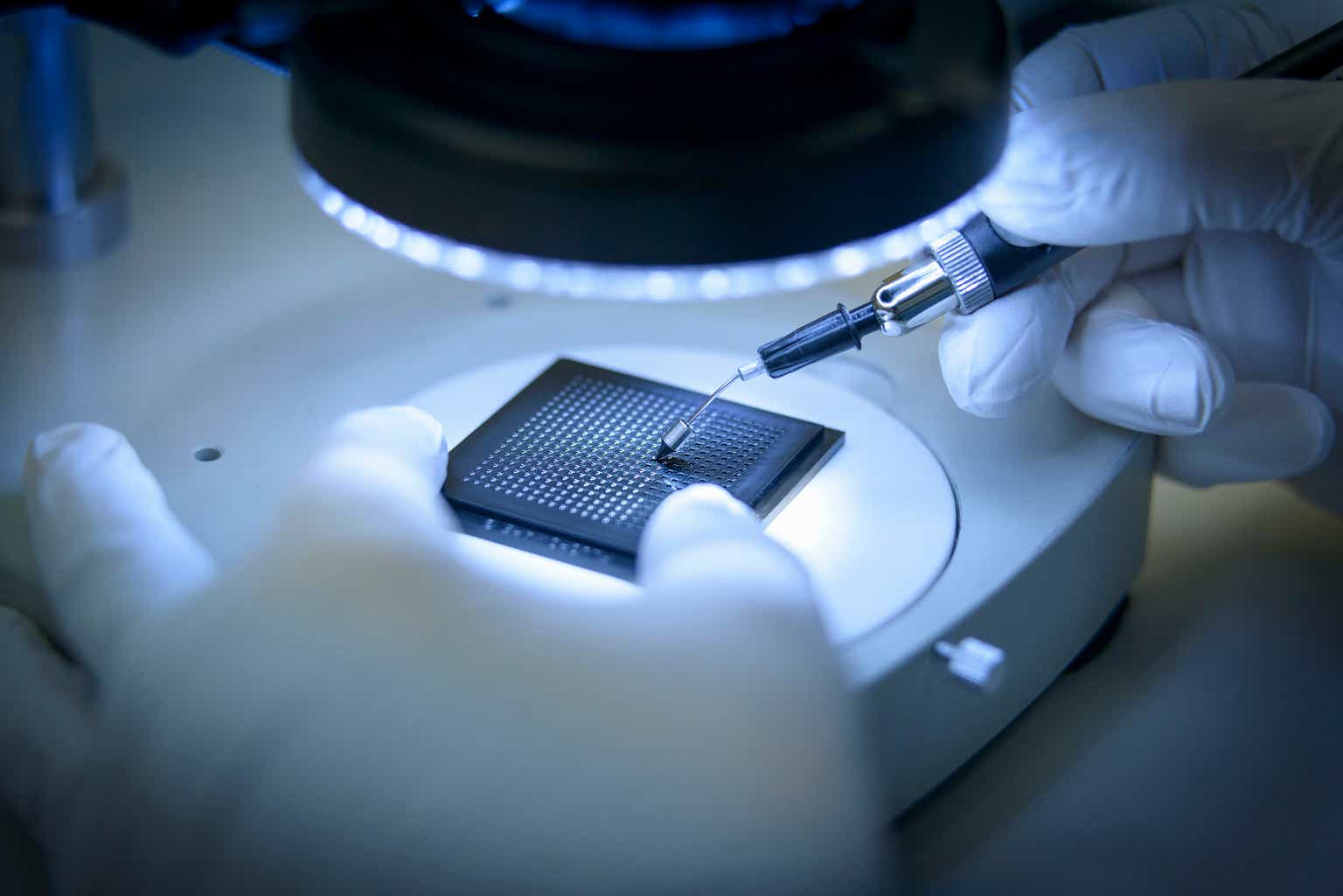

Although chemical weapons are technically and legally not allowed to be used in combat scenarios, several countries have or may attempt to do so should they believe they could get away with it. This would cause severe harm to the troops facing said weapons. But a research team from Washington University in St. Louis (WashU) was recently awarded a $1 million contract from the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) that could minimize damage for troops. Dr. Jennifer Heemstra, who will be the chief investigator on this research, will be exploring new detection methods for mustard gas. Mustard gas, also known as sulfur mustard, is a vesicant — an agent that causes blistering. Although not always immediately deadly, mustard gas has severe long-term complications, including moderate-to-severe lung and skin lesions, as well as eye damage and vision loss. Dr. Heemstra’s work could help U.S. troops identify potential toxins on the battlefield, which would allow military personnel to find ways to minimize risk. (Check out the world’s deadliest and most controversial weapons — and the global push to ban them.)

Today, many people seem more concerned about the potential for nuclear war than for chemical war. However, should chemical warfare make a resurgence, it could be highly damaging — not just n the United States, but across the globe. Here, 24/7 Wall St. put together an overview of chemical weapons, including a history of chemical weapons, types of chemical weapons, treaties in place to inhibit the use of chemical warfare, and which countries could potentially have a stockpile of weapons. To do so, we used several scholarly sources, Britannica, data from the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, and the Arms Control Association (among others).

This previously published article was updated on March 31, 2025 to reflect the recent and seemingly increasing use of chemical weapons in conflict zones such as Sudan.

Why We Need to Talk About Chemical Weapons Now

Despite a 1997 treaty on chemical weapons which eliminated 97% of global chemical weapon stockpiles, the use of these harmful tools continues to persist today. On March 24, 2025, World Without War, an international non-governmental organization (NGO) looking to end armed conflict, condemned the purported use of chemical weapons used by the Uganda People’s Defense Force (UPDF) against South Sudanese civilians. The organization’s press release suggests that the UPDF attacked citizens with ethyl acetate. This flammable chemical is toxic when inhaled and can cause serious organ damage. Just weeks earlier, remarks at a UN Security Council briefing centered around the prior use of chemical weapons by the Assad regime in Syria. The remarks argued that “all elements of the Assad regime’s chemical weapons program must now be secured, declared, and safely destroyed under international verification,” both to ensure Chemical Weapons Convention compliance and make sure any remaining chemical weapons cannot be used in violent or damaging ways.

Given the recent resurgence of these conversations, discussing chemical warfare — and how chemical weapons could be deployed, and by whom — is incredibly important. Understanding the threat these weapons pose can help prevent their spread and use. In addition, understanding which countries could potentially develop chemical weapons helps in assessing risks and where to allocate resources for national defense.

Learn more about chemical weapons and the treaties in place to prevent their use:

What are Chemical Weapons?

A chemical weapon is a device intended to kill or injure people by disbursing toxic chemicals. They are considered weapons of mass destruction, along with nuclear or biological weapons, because they are intended to inflict large numbers of casualties. Many chemical weapons injure by irritating the eyes and lungs. But these weapons are dangerous because of the breadth of their effects, which may include:

- Blistered and burnt skin

- Internal bleeding

- Confusion

- Blindness

- Vomiting

- Convulsions

- Loss of consciousness / coma

- Paralysis

- Death

Mild Chemical Weapons

Mild versions of chemical weapons, such as tear gas, mace, and pepper spray, are legal around the world. You might have seen them deployed by riot police for crowd control, or in a smaller setting such as hand-held canisters for self-defense. However, if these weapons were instead deployed on a larger scale during a military conflict, this would be considered an illegal use of chemical weapons in warfare.

Militarized Chemical Weapons

The Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) explains that chemical weapons may include precursors to chemical weapons, fully developed weapons and their components, chemicals used to cause intentional harm or death, dual-use items, munitions and devices to deliver toxic chemicals, and equipment for those munitions and devices. If you’re more looking for specific ways chemicals have been weaponized — and what those effects may be — then check out the following list. Some of these weapons are so potent that they can kill quickly with as little as a drop on the wrist:

- Chloropicrin: irritation to the eyes, skin, and lungs, loss of consciousness

- Cyclosarin: muscular and respiratory problems, confusion, loss of consciousness

- Lewisite: blindness, respiratory problems, painful blistering of the skin and eyes, vomiting, diarrhea, pulmonary edema

- Methylphosphonothioic acid (VX): convulsions, respiratory failure, paralysis, loss of consciousness

- Nitrogen mustard: blisters, nausea, secondary cancer risk, internal bleeding, eye irritation, cough

- Phosgene oxime: respiratory irritation, eye and skin pain

- Sarin: muscular and respiratory problems, convulsions, confusion, loss of consciousness

- Soman: muscular and respiratory problems, convulsions, paralysis, loss of consciousness

- Sulfur mustard (Yperite): blisters and burns, blindness, vomiting, shock

- Tabun: muscular and respiratory problems, convulsions, paralysis, loss of consciousness, pinpoint pupils, abnormally high or low blood pressure

Chemical Weapons in Battle

While many people believe that Germany was the first country to use chemical weapons after firing 150 tons of chlorine gas at French troops in 1915, this is actually incorrect. In actuality, France launched bromine ethyl acetate tear gas grenades the year before in August 1914. The Allies then began weaponizing chemicals on a greater scale. By the end of World War I, approximately 1.3 million people were victims of chemical warfare. 90,000 people died — and many dealt with lifelong disabilities.

Chemical weapons were not used on the battlefield in World War II, but Germany used them to commit mass murder during the Holocaust. In modern times, Iraq and Syria are both notorious for having used chemical weapons against their own people. The United Nations estimates that chemical weapons have caused more than 1 million casualties globally since World War I.

What Military Strategy Could Chemical Weapons Serve?

As weapons of mass destruction, chemical weapons could potentially serve some of the same functions as nuclear weapons in a country’s military strategy. These include:

- Deterrence: the threatened use of chemical weapons could prevent a country from being attacked by an enemy or force them to make peace.

- Countries without nuclear capacities could use the threat of chemical weapons to potentially deter attacks by nuclear power.

- Retaliation: taking revenge against a country that used chemical, nuclear, or biological weapons against a chemically-armed country.

- Mass Casualties: in a situation where a country faces a much stronger or more numerous foe, chemical weapons could even the playing field by neutralizing large numbers of troops.

Chemical weapons have not been decisive in previous conflicts, however, and have just brought international condemnation and sanctions down on countries that use them. Moreover, unlike technologically more complex nuclear or biological technologies, any country with an adequate industrial base can produce toxic chemicals that could be weaponized. Therefore, any battlefield advantage of using them would be short-lived.

Treaties Against Chemical Weapon Use

Post World War I, soldiers returned home with terrible, life-threatening injuries — and this sparked a huge outcry against the use of chemical weapons. This eventually led to the Geneva Protocol, also known as the Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare. Drafted and signed in 1925, the treaty prohibited the use of chemical weapons and some biological weapons. However, several countries opted not to sign the treaty, and several countries who did sign the treaty continued producing chemical weapons regardless.

Nearly 70 years later came the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC). This 1993 treaty set out to once again ban the use of chemical weapons. 193 parties are subject to the treaty, though there are only 165 signatories; several countries have ratified or accepted the CWC, though did not initially sign it. The Chemical Weapons Convention required the destruction of all chemical weapons by 2012. These eight countries declared that they had chemical weapons stockpiles and agreed to destroy them under the supervision of international monitors:

- Albania

- India

- Iraq

- Libya

- Russia

- Syria

- United States

- An anonymous country; probably South Korea

The Only Country With Known Chemical Weapons

As of 2023, North Korea was the only country known to still have chemical weapons. Military analysts believe this hostile country has 2,500-5,000 metric tonnes of chemical weapons, including mustard, phosgene, and nerve agents. They are also suspected of having biological weapons such as anthrax, smallpox, and cholera. They have about 50 nuclear weapons and can produce 6 to 7 more every year. Their ballistic missiles have the range to strike anywhere on Earth except South America.

Countries That Could Have Chemical Weapons

In addition to North Korea, three other countries are not yet fully part of the Chemical Weapons Convention treaty. Although Israel signed the treaty in 1993, the country’s parliament never ratified it; this means that Israel has not formally accepted the rules and regulations of the treaty. Egypt and South Sudan have also not chosen to sign the Chemical Weapons Convention.

Moreover, these 14 countries all declared a total of 97 chemical weapons production facilities that have now been deactivated or converted to civilian use. Of course, it is possible that converted or destroyed facilities could be converted back again or rebuilt. The significance of this list is not to say these countries are still producing chemical weapons, but that they have the proven technical capability to do so.

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- China

- France

- India

- Iran

- Iraq

- Japan

- Libya

- Russia

- Serbia

- Syria

- United Kingdom

- United States

The post If Chemical Weapons Return, We’re All in Danger – Here’s Why appeared first on 24/7 Wall St..