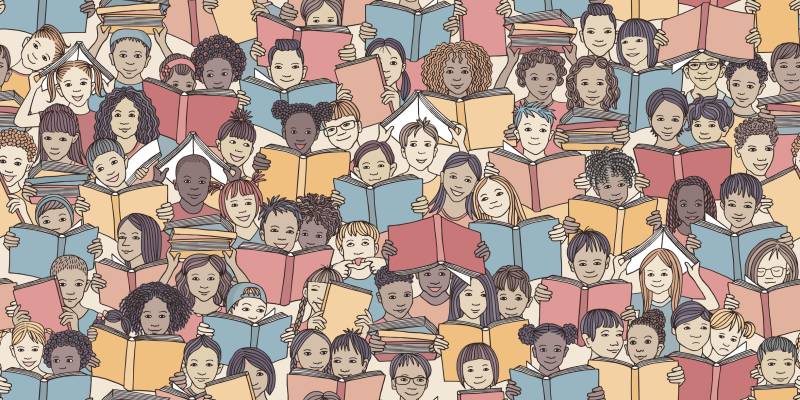

Hundreds of thousands of students are entitled to training and help finding jobs. They don’t get it

There’s a half-billion-dollar federal program that is supposed to help students with disabilities get into the workforce when they leave high school, but most parents — and even some school officials — don’t know it exists. As a result, hundreds of thousands of students who could be getting help go without it. New Jersey had […] The post Hundreds of thousands of students are entitled to training and help finding jobs. They don’t get it appeared first on The Hechinger Report.

There’s a half-billion-dollar federal program that is supposed to help students with disabilities get into the workforce when they leave high school, but most parents — and even some school officials — don’t know it exists. As a result, hundreds of thousands of students who could be getting help go without it. New Jersey had the nation’s lowest proportion — roughly 2 percent — of eligible students receiving these services in 2023.

More than a decade ago, Congress recognized the need to help young people with disabilities get jobs, and earmarked funding for pre-employment transition services to help students explore and train for careers and send them on a pathway to independence after high school. Yet, today, fewer than 40 percent of people with disabilities ages 16 to 64 are employed, even though experts say most are capable of working.

At a time when Americans have made clear that access to training and good jobs is a top priority, a program that could be providing that for one of the nation’s most vulnerable populations is, in many states, serving a fraction of the students it should. When it does reach students, the programming is often inadequate, and states like New Jersey face almost no accountability for their shortcomings.

Only about 295,000 students in the whole country received some form of the services — out of an estimated 3.1 million who were eligible — in 2023, the most recent year for which data is available. In New Jersey last year, that number was just 1,370 students out of more than 80,000 eligible. In New York, about 5 percent of eligible students got services.

“If young people have an opportunity to be exposed to the world of work, and they get services ahead of time, they can work independently in the community. They can be a part of society,” said Maureen McGuire-Kuletz, co-director of the George Washington University Center for Rehabilitation Counseling Research and Education. “That was the hope. If you got in early, then some challenges later on would not exist.”

Related: Become a lifelong learner. Subscribe to our free weekly newsletter to receive our comprehensive reporting directly in your inbox.

Officials at the U.S. Department of Education, which oversees vocational rehabilitation services and, by extension, pre-employment transition services, acknowledge that pre-ETS must be made available to all students with disabilities. They point out, however, that the law doesn’t mandate that all students receive the services. Not all students choose to get them, and some students may get the help they need from their schools, Danté Q. Allen, the commissioner of the department’s Rehabilitation Services Administration commissioner until last month, said in an email.

Bridgette Breece’s son did well with the hands-on work at his high school in western New Jersey, but his disabilities made reading difficult, and he struggled with textbook-based exams.

Worried about her son’s future, Breece tried to get him some career help before graduation. She saw a Facebook post about the state vocational rehabilitation agency set up for exactly that purpose. But she says the VR counselor told her that her son wasn’t eligible until he turned 18 — which was untrue.

After Breece’s son graduated last spring, he found a job as a tow truck driver, which he was good at and enjoyed. But the company required all employees to take turns periodically being on call for overnight emergencies. His anxiety disability made him terrified that he would miss a call, so he didn’t sleep for several nights in a row and had to quit.

Pre-employment training, which he should have gotten in high school, could have taught him how to request an accommodation or how to explore jobs that fit his abilities and interests. But he never got that. His mom — like most parents in New Jersey — had no idea the pre-ETS program existed. She’s had to apply for social security benefits for him, something neither of them ever wanted.

“He’s embarrassed,” she said. “My heart breaks for the kid. He wants to work, he wants to do good. I just wish we could have gotten help while he was still in high school.”

Related: Help The Hechinger Report investigate special education

For more than 30 years, federal education law has required schools to help students with disabilities plan for their transition out of high school. But there’s often a gap between what a school can provide and the kind of training or counseling a student needs. That’s where the pre-employment services — provided through state vocational rehabilitation agencies — are supposed to help. A student who is visually impaired may need to learn computer software that allows them to work in an office, for example, while a student with Down syndrome might benefit from receiving job coaching while working in a cafe.

“Every student, disabled or not, needs assistance in career planning and services,” said Daniel Van Sant, who is the director of disability policy at the Harkin Institute at Drake University. “It’s just that disabled students might have additional needs because of inaccessibility in our society. Our system generally is not accessible for people with disabilities to enter the workforce.”

Before 2014, state vocational rehabilitation agencies primarily worked with adults. That changed when Congress directed the agencies to offer services geared to employment for all students with disabilities, starting as early as age 14.

But most New Jersey students, through no fault of their own, never get the option. Interviews with dozens of advocates, educators and parents depict a confusing bureaucratic maze, one that leaves tens of thousands of students without services. For 10 years, the state’s pre-employment program has languished, with leadership turnover and bureaucratic infighting rendering it largely ineffective. And the state’s extremely decentralized school governance system has hampered haphazard efforts to get the services into schools.

New Jersey officials acknowledge that there’s a problem.

“We know that there’s not enough people who are fully aware of all of our services,” said Charyl Yarbrough, assistant commissioner of employment accessibility services at New Jersey’s Department of Labor and interim director of the state’s division of vocational rehabilitation services. “Nobody wants to be a best-kept secret.”

New Jerseyuses outside contractors — primarily nonprofit organizations and universities — to provide most of its services, and spent $14.6 million in federal and state funds in 2023, the last year that complete data is available.

Related: The ‘forgotten’ part of special education that could lead to better outcomes for students

New Jersey Department of Labor officials say they have boosted outreach and increased the number of students receiving services and that a core obstacle is inconsistent relationships with schools.

But at the district level, school staff say it’s difficult to reach overburdened state VR counselors and, when they do, delays leave parents and students waiting for months. Some eventually give up. In other cases, VR counselors assigned to the high schools say it’s difficult for them to reach school staff, and when they do, they are sometimes denied access, with the school claiming they’re already providing everything the students need. Either way, parents are left in the dark.

Maureen Piccoli Kerne, who started a transition program at a New Jersey high school and is now a consultant, has seen the program work, and says that the counseling before job placement is crucial.

“It’s important because then they know what they like to do,” she said. “They know what their strengths are. They know how to ask for accommodations at work.”

She recently worked with a young woman who loves libraries. Her developmental disability prevented her from attending a traditional college, but she took courses online and became a librarian’s assistant at a public library in Long Island.

“She was so excited about the courses,” said Kerne. “She has a job she loves, and she’s being productive, and that’s what can happen when you work with young people early, listen to them and set them up to succeed.”

Another fan of the program, Linda Mauriello, runs the transition and work-based learning program at Boonton Public Schools in northern New Jersey. Staff from community-based organizations come to school to train students on how to build relationships at work, create resumes and set career goals. They also provide support at workplaces.

One of her students with multiple disabilities trained at the school cafeteria; he was hired and five years later is still working there. Another student with autism did his work-based learning at the local Walgreens, learning time management as well as working with customers. He was hired and is now in charge of opening up the store.

“I think the pre-ETS program is a great program,” Mauriello said. “My students have really benefited from it.”

Some schools in New Jersey have forged good relationships with state VR counselors, enabling families to find outside providers who help students connect with trial work experiences. And some provide high-quality transition services on their own, without the help of the state’s vocational rehabilitation agency. But in most cases, the disjointed system is broken.

“We’re now 10 years out, but everybody’s still struggling to get pre-ETS accessible across the state,” said Gwen Orlowski, executive director of Disability Rights New Jersey. “It’s just dysfunctional. For so many, it’s just not working.”

The Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act in 2014 mandated that vocational rehabilitation agencies dedicate at least 15 percent of the money they receive from the federal government to providing transition services to young people. But many states balked at being asked to offer services to thousands of additional people without a budget increase.

Gradually, some states forged a smoother process that eases the burden on schools and creates a partnership between agencies. In Iowa, for example, students can get pre-employment counseling at school and then be connected to internships or job trials that need to happen outside of school. In 2023, more than 40 percent of eligible students in Iowa received some kind of pre-employment services — the highest proportion in the country.

“The school-based employees have been the most successful,” said Mary Jackson, Iowa’s transition services bureau chief for vocational rehabilitation services. “Students and parents see them immersed in the culture of the school. They get to know the students, and it builds knowledge and trust.”

In New Jersey, in-school services are the exception. Most students are referred for services elsewhere. Once a referral is made, a VR counselor (who more often than not is carrying a caseload of more than 100 clients) must approve the student for services. After that, the student is usually referred to an outside provider who then has to circle back to the student to set up an appointment. The process can take months.

In some areas there’s also a shortage of providers who can work with young people.

Some nonprofits that used to offer services went out of business in the wake of Covid. Some students don’t have the internet access they need to work with counselors remotely. And because pre-ETS for the most part doesn’t pay for transportation to a job site or a training program, schools and parents are left to figure out how to get students to the offsite services.

“As we better understand what isn’t working in how we’re delivering these services and what is working,” Yarbrough said, “we are including the growth of these services as a core component of our strategic priorities.”

Policy advocates say lack of oversight by the federal government — as well as by state agencies — has meant that there is little consequence for the massive gaps in access to services. The Rehabilitation Services Administration conducts annual reviews of vocational rehabilitation agencies, but some states go years without fixing problems.

“We’ve been wanting greater oversight, meaning RSA itself needing to take a much stronger role in terms of accountability and oversight of what’s going on with states,” said Julie Christensen, executive director of the Association of People Supporting Employment First, “because it shouldn’t be the wild, wild west.”

Education Department officials say that existing oversight mechanisms are leading to improvement. In 2021, 23 states were spending less on pre-ETS than the 15 percent required by law. That number dropped to 10 states in 2022, the most recent year for which data is available.

Zoe Sullivan, who has Down syndrome, has been saying since she was in ninth grade that she wants to go to a four-year residential college program, but her mom, Kim Brooks, says no one really listened.

“I want to go to a college,” said Zoe, now a senior at Collingswood High School, as she sat outside a cafe near her home on a sunny fall afternoon. “I want to take classes and learn to be independent.”

Last spring, Brooks found out, very much by accident, about a nonprofit college prep program for students with developmental disabilities — she saw it on a friend’s Instagram post. Last fall she was scrambling to submit applications to programs that she and Zoe have found only through word of mouth and hours of research.

“It’s like a secret society,” said Brooks. “You don’t know what you don’t know. We really missed a lot of years.”

Sarah Butrymowicz contributed reporting.

Contact staff writer Meredith Kolodner at 212-870-1063 or kolodner@hechingerreport.org.

This story about pre-employment transition services, or pre-ETS, was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger Higher Ed newsletter.

The post Hundreds of thousands of students are entitled to training and help finding jobs. They don’t get it appeared first on The Hechinger Report.