How a little-known Texas city turned into the energy export gateway of the country

The completion of a channel deepening and widening project is taking the booming Port of Corpus Christi to new heights—and depths.

On New Year’s Eve on the last day of 2015, the Port of Corpus Christi quietly exported the United States’ first crude oil barrels in 40 years just two weeks after Congress lifted the ban that dated back to the 1973 Arab oil embargo.

Less than a decade later, the sleepy Texas beachside city has expanded rapidly into America’s largest energy export gateway through a network of pipelines, storage tanks, docks and, this week, the completion of a prolonged ship channel dredging and widening project that should soon allow the single port to ship out almost as much crude oil as Iraq.

“It’s very similar to the real estate markets: Location, location, location,” Port of Corpus Christi CEO Kent Britton told Fortune, noting that the port’s total tonnage volumes have essentially tripled in a decade. “The growth has been just astronomical. It’s truly astonishing.”

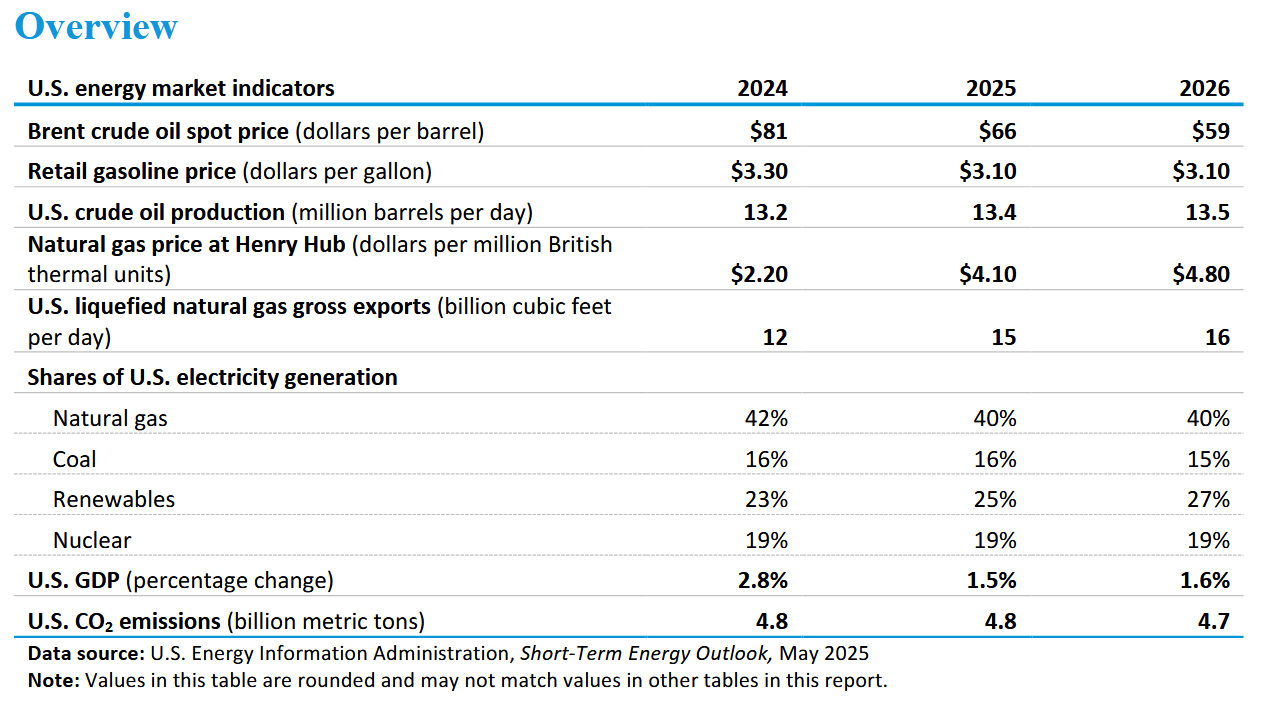

The port is now shipping out more than 2.4 million barrels of oil daily—roughly 60% of the entire nation’s crude exports—and almost 20% of the country’s liquefied natural gas exports. Those LNG volumes are expected to almost double in a couple of years once LNG pioneer Cheniere Energy completes a series of expansions.

Corpus Christi offers a series of logistical benefits for liquids that cannot be matched by the much larger Houston Ship Channel or any other ports. Corpus Christi is the closest to West Texas’ landlocked Permian Basin, which began to boom along with the lifting of the export ban. Corpus is much less congested than Houston, and Corpus easily opens up to the Gulf of Mexico’s deep waters, especially now that the port is dredged to 54-foot depths throughout.

“I think there’s a there’s a little bit of luck involved in just fortuitous timing,” Britton said. “But there was also a concerted effort on the port’s part to say, ‘We’re going to have the deepest ship channel on the Gulf Coast, and you should be coming here.’”

Long time coming

The federal feasibility study to expand the port started way back in 1990 only for the funding not to start flowing until 2018—such is the pace of bureaucracy, but well timed after the lifting of the export ban—when heavy construction began for the first of four phases—all of which are now finished.

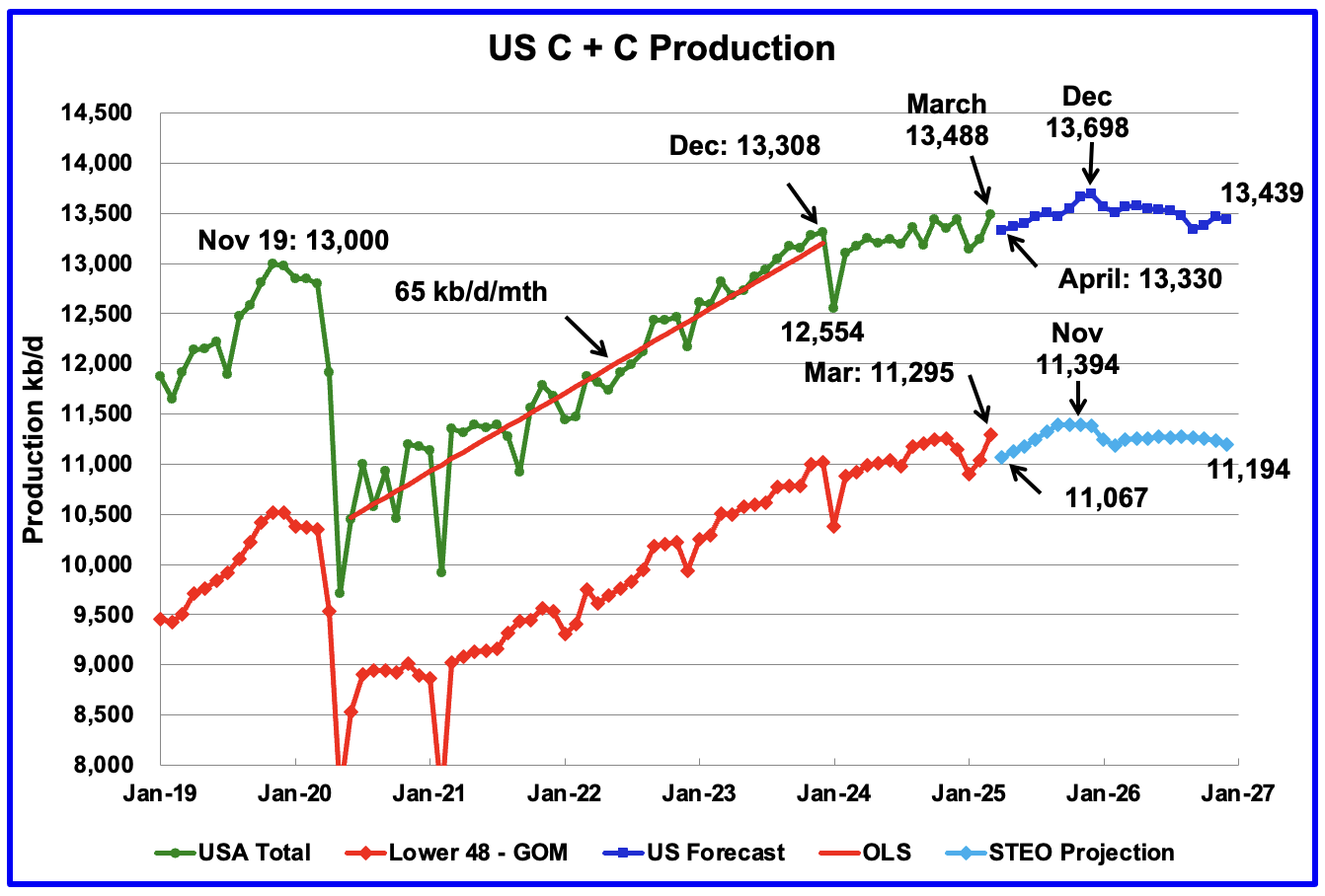

Likewise, Permian Basin and overall U.S. oil and gas production spiked to the record highs of today.

“As the Permian production grew, your exports grew, and the Corpus docks grew,” said Kristy Oleszek, director of crude oil at East Daley Analytics. “They were all growing in tandem. And not by coincidence.

“The Permian barrel is a very desirable quality to export,” she added. “One thing Corpus really provides is direct access from the Permian to the docks.”

The Permian and Corpus may be more than 450 miles apart across most of Texas connected via long-haul pipelines, but it’s still a straight path without much traffic in between.

The Corpus channel improvement project cost $625 million and is projected to save customers up to a combined $200 million per year by speeding up the trips of crude carriers and using fewer vessels. Smaller ships will no longer be needed as much to top off the bigger crude carriers in deeper waters because they couldn’t fully load at the shallower 47-foot depths—a time-consuming and expensive extra step.

“We’re moving more crude oil now than we were five years ago with fewer ships,” Britton said, with traffic now more focused on very large crude carriers (VLCCs) and Suezmax tankers. The Suezmax, which holds 1 million barrels, can now fully load at the deeper depths.

Even amid weaker crude prices and the Permian maturing and its production potentially plateauing, Britton still sees Corpus’ export volumes growing to as much as 3 million barrels a day in the next couple of years as more pipeline and dock expansions are completed.

“Other than the original creation of the port, this is probably the most significant project we’ve ever done, both from a cost perspective and from an impact on world markets,” he said.

Fortuitous occurrences

Before the port’s improvement project started, there were two key and somewhat serendipitous events initiated separately by Occidental Petroleum (159 in the Fortune 500) and Cheniere (275 in the Fortune 500).

Already positioned with an OxyChem petrochemicals facility by Corpus, Occidental bought the shuttered Naval Station Ingleside by the port in 2012 for just $82 million to transform it into an export terminal for its products.

After the lifting of the crude export ban, Oxy focused on making its renamed Ingleside Energy Center a prime oil-exporting hub. After building it out, Oxy sold it as part of a terminals and pipelines package for $2.6 billion in 2018.

Enbridge, the largest midstream pipeline and terminal company in North America, then bought it for $3 billion in 2021 and has continued to grow it ever since, including new storage tank construction ongoing now. Enbridge also is expanding its Gray Oak Pipeline to transport even more oil from the Permian to Corpus for export.

The Enbridge Ingleside Energy Center is by far the largest oil-exporting terminal in the Americas, able to simultaneously load two VLCCs—the largest oil tankers that can carry 2 million barrels of oil each.

And Enbridge is just one of several oil exports at the port.

Likewise, Cheniere first began planning Corpus Christi LNG way back in 2003, but it was designed as a gas-import project long before the U.S. was approaching any degree of energy security following the shale oil and gas boom that took off shortly thereafter.

Cheniere soon pivoted, building Corpus Christi LNG as the first large, greenfield LNG export project built in the country. Construction started in 2015 and exports commenced in 2018.

“They did such a fabulous job pivoting from that import play when the shale revolution started, and everyone realized that we were going to have excess gas to become an exporter,” Britton said of Cheniere. “They just they just hit it right. They get a little lucky on the timing as well, but it was a lot of vision and recognition of what’s going on in the market to flip that switch.”

As a result, the U.S. became a net energy exporter for the first time ever in late 2019—a position that’s only been strengthened ever since.

Cheniere is currently completing a third phase of Corpus Christi construction by late 2025 or early 2026, and then a midsized follow-up project is planned to take Corpus Christi LNG to an export capacity of 16.5 million metric tons of LNG annually now to more than 30 million metric tons. Cheniere has the acreage for a fourth phase of expansions but has not yet made any decisions.

“LNG is really taking off,” Oleszek said. “Crude oil kind of had its day in the sun and now it’s moved over to LNG. Crude oil is still growing, but not nearly as much [as gas].”

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com