Goldman Sachs says Trump’s spending plan won’t stop the national debt from hitting ‘unsustainable’ highs not seen since World War II

If borrowing costs remain high, future lawmakers could be left in a tough spot.

- The U.S. will pay $1 trillion in interest on the $36 trillion national debt next year, more than it spends on Medicare and defense. If lawmakers wait too long to address deficits, Goldman economists warn, a historic austerity push could be needed to avert disaster.

President Donald Trump has claimed the GOP’s “Big, Beautiful” bill will put the U.S. on a sustainable fiscal path. Economists at Goldman Sachs say it won’t prevent the nation’s debt from surpassing levels only seen during World War II.

The spending bill passed by House Republicans, combined with increased tariff revenue, will slightly lower the budget deficit when excluding interest payments, Goldman’s Manuel Abecasis, David Mericle, and Alec Phillips acknowledged in a note Tuesday. Coupled with rising borrowing costs, they said, the bill leaves the total deficit’s course essentially unchanged.

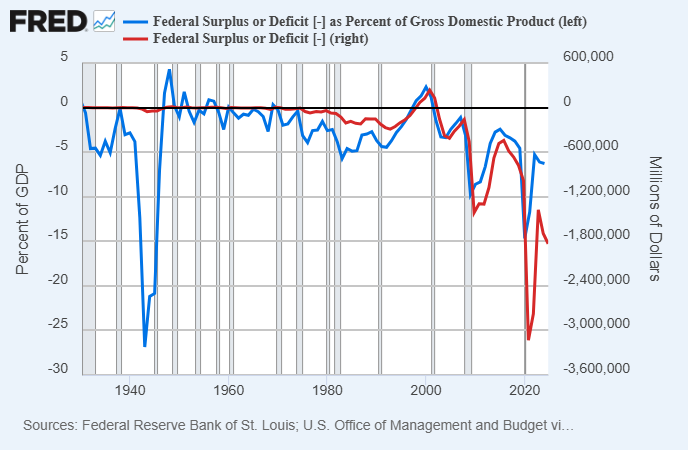

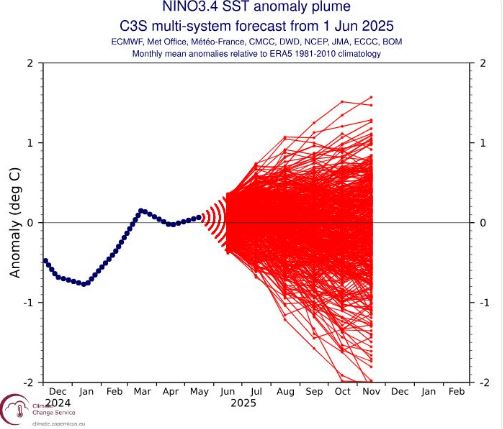

“But that path remains unsustainable: the primary deficit is much larger than usual in a strong economy, the debt-to-GDP ratio is approaching the post-[WWII] high, and much higher real interest rates have put the debt and interest expense as a share of GDP on much steeper trajectories than appeared likely last cycle,” the Goldman team wrote.

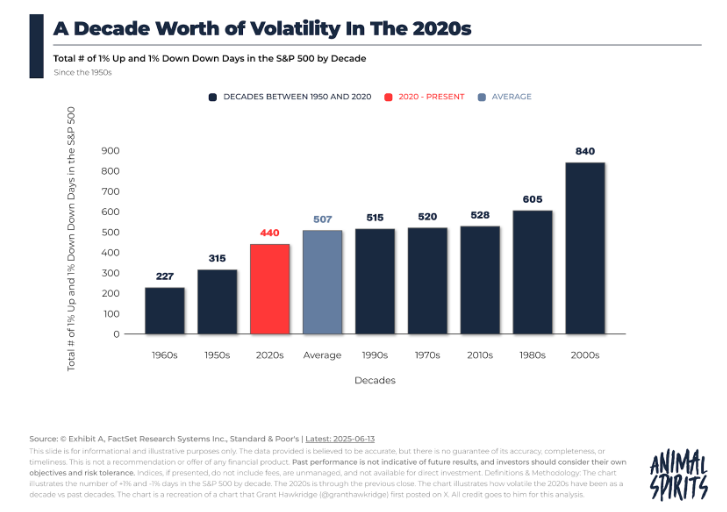

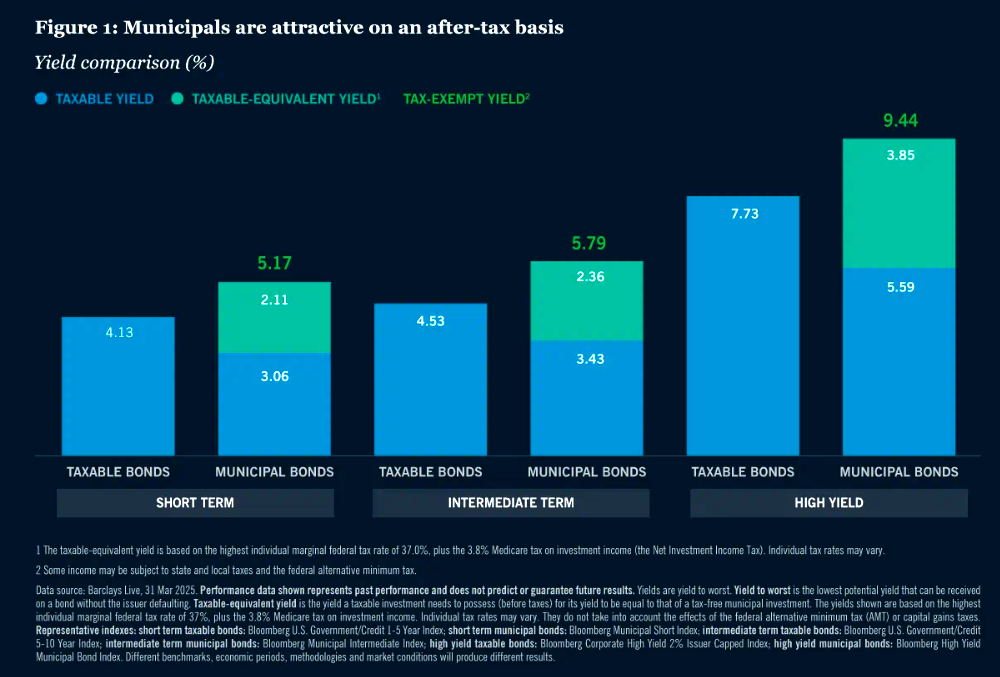

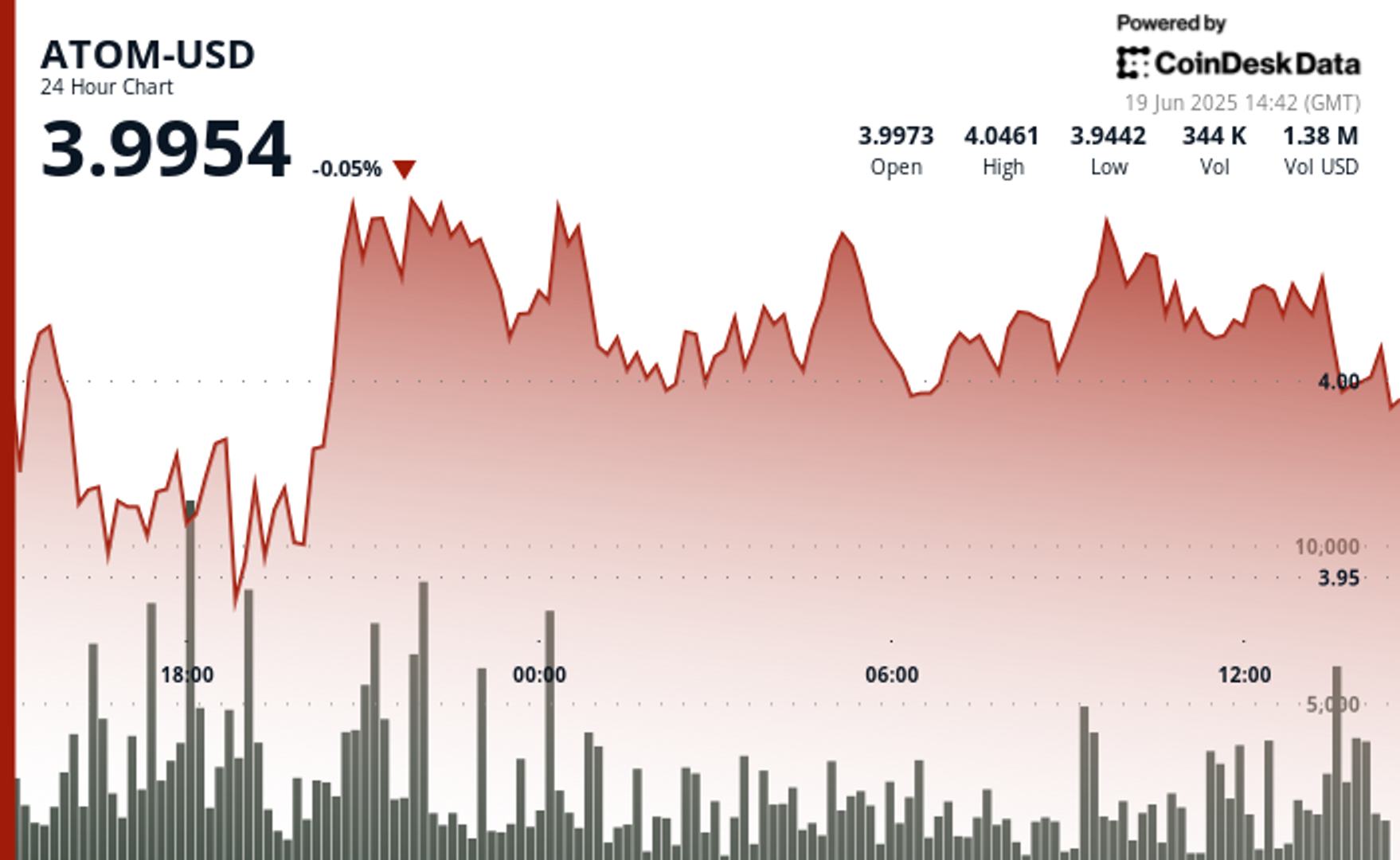

As the charts above show, the scale of the debt going forward depends greatly on how interest rates move over the next couple decades. Right now, the $36 trillion national debt accounts for roughly 120% of GDP, and the Treasury Department finds itself borrowing more just to meet the rising cost of servicing it.

The U.S. pays more in interest on its debt than it spends on Medicare and defense. Those interest payments will hit $1 trillion next year, trailing only Social Security as the government’s biggest outlay, according to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, a think tank.

“If the debt grows large enough,” the Goldman team wrote, “interest expense could become so large that stabilizing debt-to-GDP would require running persistent fiscal surpluses of a size that has seldom been sustained historically because it is economically costly and politically difficult.”

The first Trump and Biden administrations responded to the COVID-19 pandemic with a wartime-like budget. But the spigot never got turned off, even when the U.S. economy moved back to full employment.

The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimates the version of the GOP spending bill passed by the House would increase deficits by $2.8 trillion over the next decade. The White House and some Republican lawmakers argue that projection should not include the cost of extending Trump’s 2017 tax cuts, which are set to expire this year without the bill.

But the crux of the $36 trillion problem is that no one knows at what level the debt becomes unsustainable, Gennadiy Goldberg, the head of U.S. rates strategy at TD Securities, told Fortune.

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has said the U.S. government has a “spending problem,” but not a “revenue problem.” Goldberg agrees with the former argument, but he said the U.S. also does not tax much compared to both the size of the country’s GDP and government outlays.

“So either taxes have to go up, spending has to come down, or some combination of the two,” Goldberg said last month. “And it sounds simple, but it’s politically very, very complicated to figure out.”

Higher interest rates would increase deficit pressure

Continuing to avoid taking action puts future lawmakers in a tighter spot, however, especially if borrowing costs rise.

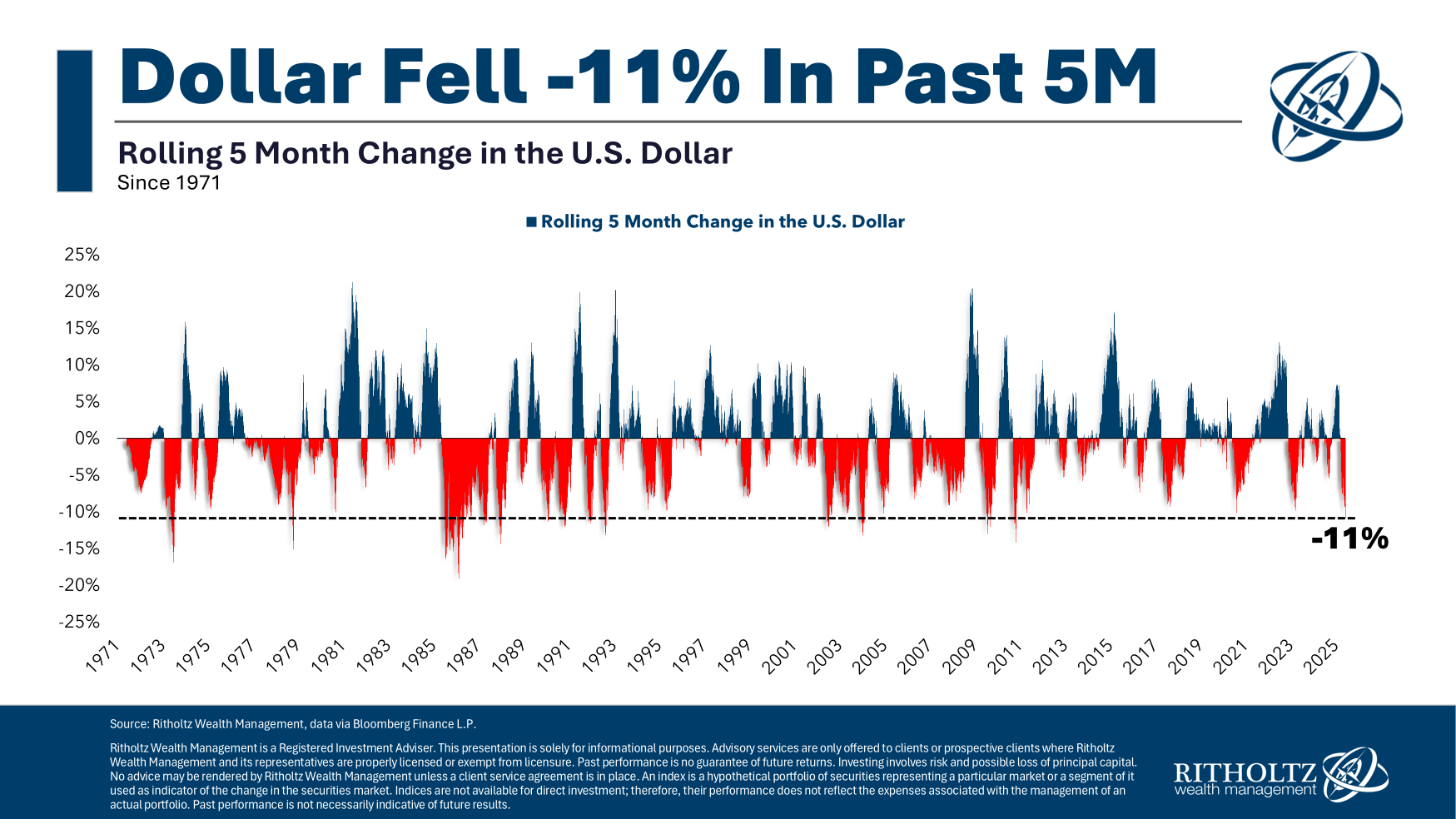

Yields on long-term U.S. Treasury bonds have remained elevated as investors wait for a patient Federal Reserve to cut interest rates, and concerns about the burgeoning deficit and a possible resurgence of inflation might also continue to put upward pressure on rates.

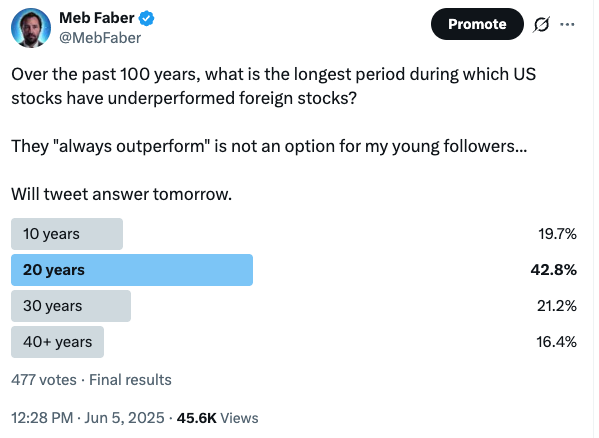

Fixed-income experts are also closely monitoring any changes to foreign demand for U.S. debt. If rising trade and geopolitical tensions undermine the dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency, the U.S. government would also find itself borrowing at higher rates than it’s become accustomed to.

That means Congress may eventually be forced to make increasingly tough choices when it comes to both spending and taxes. If lawmakers wait too long, a historic austerity push could be needed to avert disaster, the Goldman team said.

“In that scenario, one might worry either that a large fiscal consolidation and a persistent fiscal surplus could be self-defeating—if GDP declines enough, the debt-to-GDP ratio might not shrink,” they wrote.

Of course, politicians would also face the temptation of printing way more money to pay the government’s bills. Germany’s Weimar Republic tried that tactic in the aftermath of World War I. It resulted in ruinous hyperinflation, fueling the economic malaise and social unrest that led to the rise of the Nazi Party.

That warning from history, however, is not always heeded by governments.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com