Finding the Beauty of Wabi-Sabi on Japan’s Kii Peninsula

Wabi-sabi is one of the most notoriously tricky Japanese terms to translate.

“The teacup in your hands is 400 years old,” the tea master told me. The ceramic vessel, glazed in soft yellow, bore a tiny crack snaking up one side. “Take a moment to contemplate the hands that have held it in the past — those of monks, poets, and samurai,” he said. Bald as a polished stone in a Zen garden and dressed in an immaculate black kimono, the tea master had spent decades studying wabi-cha, the traditional tea ceremony from Nara.

He whisked matcha in a ceramic bowl, and the emerald-green powder released a briny perfume into the small room adorned with wall scrolls and hinoki wood paneling. Before serving the brew, he asked me to examine my teacup again: “Every teacup has a face, where you place your lips.” My teacup’s face was directly opposite the thin crack, allowing me to admire the zig-zag-shaped fracture while savoring the matcha.

My teacup, the tea master explained, epitomized the ideal of wabi-sabi, a cornerstone of Japanese spirituality and aesthetics. The term loosely means “beauty in imperfection,” but it carries more nuanced meanings, like the bittersweetness of impermanence, pleasure in rustic design, and reverence for anything artfully weathered, aged, or imperfect. It’s one of the most notoriously tricky Japanese terms to translate, and a concept I was struggling to wrap my mind around even after weeks in Japan.

Tea ceremonies are an ancient art throughout Japan. Photo: Nakagawa Masashichi Shoten

As I studied my teacup and the matcha’s generous hit of caffeine kicked in, it finally clicked. I began to understand why the Japanese see profound beauty in lopsided stones, frayed vintage t-shirts, and ancient teacups. Like the creases etched into an elder’s face from a lifetime of joy and sorrow or a temple staircase polished from centuries of footsteps, imperfections allude to the stories and emotions intertwined with the passage of time. Wabi-sabi conveys a more poignant pathos than perfect symmetry ever could.

Many such insights into Japanese spirituality unfolded during my trip through the Kii Peninsula, a region south of Osaka that includes the Mie, Nara, and Wakayama prefectures. It’s sometimes known as the “Prayer Room of Japan” and is home to Ise Jingu (the most sacred Shinto shrine), as well as Todai-ji, one of the oldest Buddhist temples in Japan.

Coastline in Wakayama Prefecture, Japan. Photo: JinFujiwara/Shutterstock

While the peninsula is most famous for its holy sites, it’s growing in popularity with outdoorsy travelers who come to explore the region’s famous hiking trails, cliff-framed beaches, and renowned hot springs. Nara has long been one of Japan’s most popular destinations, but the Kii Peninsula’s smaller towns, most within a quick drive of a Shinkansen station, are almost free of tourists and offer a window into Japan’s rural culture. And with regional delicacies like spiny lobster, matsusaka beef, and multi-course kaiseki feasts in luxurious ryokans, the Kii Peninsula is as appealing to epicureans as spiritual seekers.

Mie Prefecture

The Tori Gate at Ise Jingu. Photo: iamlukyeee/Shutterstock

Mie is blessed with dazzling coastlines, verdant mountains, grassy plains, and cedar forests. It’s three hours by bullet train from Tokyo and home to large sections of the Kumano Kodo, an ancient pilgrimage route connecting various Buddhist and Shinto holy sites. In past centuries, emperors and samurai traveled the sacred trails alongside monks, farmers, and fishermen. Today, much of the Kumano Kodo is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. And just as the Camino de Santiago, Spain’s famous pilgrimage trail, has one site more important than all others (Santiago de Compostela), so too does the Kumano Kodo Trail: Ise Jingu.

Dedicated to Amaterasu Omikami, the Shinto sun goddess and mythical ancestor of the Japanese imperial family, Ise Jingu is the most hallowed ground on earth for Shinto practitioners. The shrine sits within Ise-Shima National Park, a 230-square-mile preserve in Mie encompassing forests and coastlines and laced with hiking trails.

The inner shrine of Ise Jingu, called the Naiku, allegedly houses the mirror Amaterasu used to see herself at the dawn of creation. Similar to how Muslims’ aspire to visit the Kaaba in Mecca, Shinto devotees (which includes a large majority of Japanese people in some fashion) aim to visit Ise Jingu at least once in their lifetimes.

The sacred forest around Ise Jingu. Photo: freedom-man3/Shutterstock

Note that the Naiku, where the Sacred Mirror is held, is strictly off limits to the public. Visitors can, however, come to the wall around the Naiku and tour the various minor shrines around the Isuzu River and its surrounding cypress forests.

With an M.A. from the Divinity School at Harvard University and a deep interest in global religions, I’ve long been drawn to Japan. And the former religious studies teacher in me couldn’t help but spend the hours following my visit thinking about Ise Jingu’s metaphysical mysteries. What’s the symbolism behind the story of Amaterasu gazing at herself in a mirror? It’s a Shinto story, but one reflected across cultures in tales of gods admiring themselves; similar stories are found in Sufi poetry and Hindu mysticism.

A section of the Kumano Kodo, and the author at Isekado Brewery. Photos: Johnny Motley

My mind started to reel, and without having Carl Jung nearby to explain psycho-mythic symbolism, I figured it was time to come back down to Earth with a beer. Fortunately, Isekado Brewery, one of my bucket-list Japanese breweries, was just a quick drive from Ise Jingu.

Founded in 1575, Isekado was originally a soy sauce kura (storehouse), but centuries of shoyu fermentation expertise proved just as useful for crafting masterful beer. Isekado has garnered craft beer awards in Japan and around the globe, and during my visit, seemed to embody the spirit of monozukuri: meticulous attention to detail and an unwavering pursuit of perfection. Isekado’s current head brewer moved to Mie from Belgium, and the brewery’s offerings include Trappist, Japanese, and hybrid styles. At the risk of sounding hyperbolic, you won’t find a tastier citrus lager in Japan, no matter how many cycles of birth and rebirth you experience.

Where to stay in Mie

A kaiseki dinner at Umi-no-Chou. Photo: Johnny Motley

Lodging options in Mie range from tranquil ryokans to grand, Western-style hotels. Umi-no-Chou is a hotel as renowned for fine dining as it is for panoramic views of the Pacific Ocean, situated on the easternmost part of the peninsula.

After donning silk yukata from their rooms, guests can settle in for a sumptuous kaiseki (multi-course) feast with Mie’s most famous proteins: spiny lobster and matsusaka beef. Like Kobe beef, matsusaka gyu (beef) comes from tajima cattle, but many connoisseurs and chefs claim it’s even better than its more famous counterpart from Kobe. Umi-no-Chou also has an impressive library of Japanese whiskies to pair with marbled slices of beef, and I was delighted to find rare whiskeys from beloved Japanese distillery Suntory, including Yamazaki and The Hakushu.

Resort Kumano Club is a compound of luxury cottages tucked in the mountains in the southern part of Mie Prefecture. Thoughtful touches include fine incense in each room and fridges stocked with local beers and sakes. Each cottage has its own kitchen and living room, and guests sleep on tatami floor mattresses – traditional bedding in Japan. The head chef at Kumano Club cut his teeth in kitchens in Italy and France, and his menu blends Japanese and continental specialties.

Wakayama

A woman in historical dress in Wakayama Prefecture. Photo: Mirko Kuzmanovic/Shutterstock

Blanketed with forests and laced with rivers, the mountainous prefecture of Wakayama is one of most sparsely populated pockets of Honshu, the main island of Japan. In addition to containing large sections of the Kumano Kodo, Wakayama is known for excellent soy sauce, persimmons, and sesame tofu, considered a rustic delicacy.

Denizens of Tokyo will tell you that Wakayama Prefecture is synonymous with inaka, the Japanese word for countryside. While it requires some effort to visit Wakayama as the prefecture lacks a bullet train station, visitors who make the trip are treated to quaint villages, stunning mountain drives, and the serene charm of Japan’s rural culture. I think of Wakayama as the South Dakota of Japan: an under-the-radar region that steals the hearts of travelers seeking natural splendor and authenticity instead of the sensory overload of places like Tokyo or Osaka.

Buddhism arrived in Japan in successive waves starting in the sixth century CE, with monks from Korea and China bringing varying interpretations of the religion across the Sea of Japan. In the early ninth century, a Japanese monk named Kūkai returned from China after studying an esoteric form of Buddhism with roots in Tibet. Kūkai championed a form of Buddhism that incorporated Shinto and mystical Japanese ideas, which became known as Shingon Buddhism. Around this time, nearby practitioners of an earlier Buddhism called Shugendō, which included Taoist principles and nature worship, embraced the teachings of Kūkai. While the two sects are still distinct today, both are present in temples and sacred sites around Koyasan and the Kumano Mountains.

Shegundo practitioners in Wayakama Prefecture, Japan. Photo: Johnny Motley

Many Shugendō and Shingon temples in Wakayama offer room and board to travelers, providing vegetarian meals and tatami mats. In these temple lodges, called shukubo, visitors may encounter yamabushi: Shugendō monks and nuns who live as hermits in the mountains. Traditional yamabushi garb includes a small box strapped to the forehead, somewhat similar to the prayer boxes (tefillin) worn by some Orthodox Jews.

The center of Shingon Buddhism is Koyasan, a temple complex deep in Wakayama’s misty mountains. Koyasan houses the earthly remains of Kūkai, who Shugendō devotees claim never died, but instead, rests in an eternal state of meditation. Today, the faithful pay their respects at Kūkai’s tomb in the Okunoin Mausoleum in the Koyasan temple complex.

A temple in the Kumano Nachi Taisha complex. Photo: Sean Pavone/Shutterstock

A three-hour drive from Koyasan is the temple complex of Kumano Nachi Taisha, which illustrates the mingling of Shinto and Buddhism so characteristic of Shegundō. In the temple complex, you’ll find statues of the Buddha and bodhisattvas (people who have reached enlightenment), but also images of Shinto nature deities. A large hollow tree stands in the temple’s courtyard, through which the faithful climb in a symbolic act of rebirth. After marveling at the temple halls and enjoying spiritual rebirth through the arboreal cervix, most visitors make the short walk to the majestic Nachi Falls. It’s the highest waterfall in Japan and a sacred site for both Buddhists and Shinto devotees.

Where to stay in Wakayama

Photo: Ryokan

It would be easy to conclude that Wakayama is a land of self-denying monks and hermits, but its high-end ryokans, rich cuisine, and inviting onsen will convince you otherwise. At Ryoken Adumaya at Kawayu Onsen, one of the oldest hot springs town in the world, guests can soak in both indoor and outdoor onsen (or day-trippers can use the baths between 1 and 3 PM). Before a nocturnal soak, enjoy a dinner of masterfully prepared jellyfish, sesame tofu, or even whale meat sashimi — three iconic delicacies from Wakayama.

Nara

Photo: ESB Professional/Shutterstock

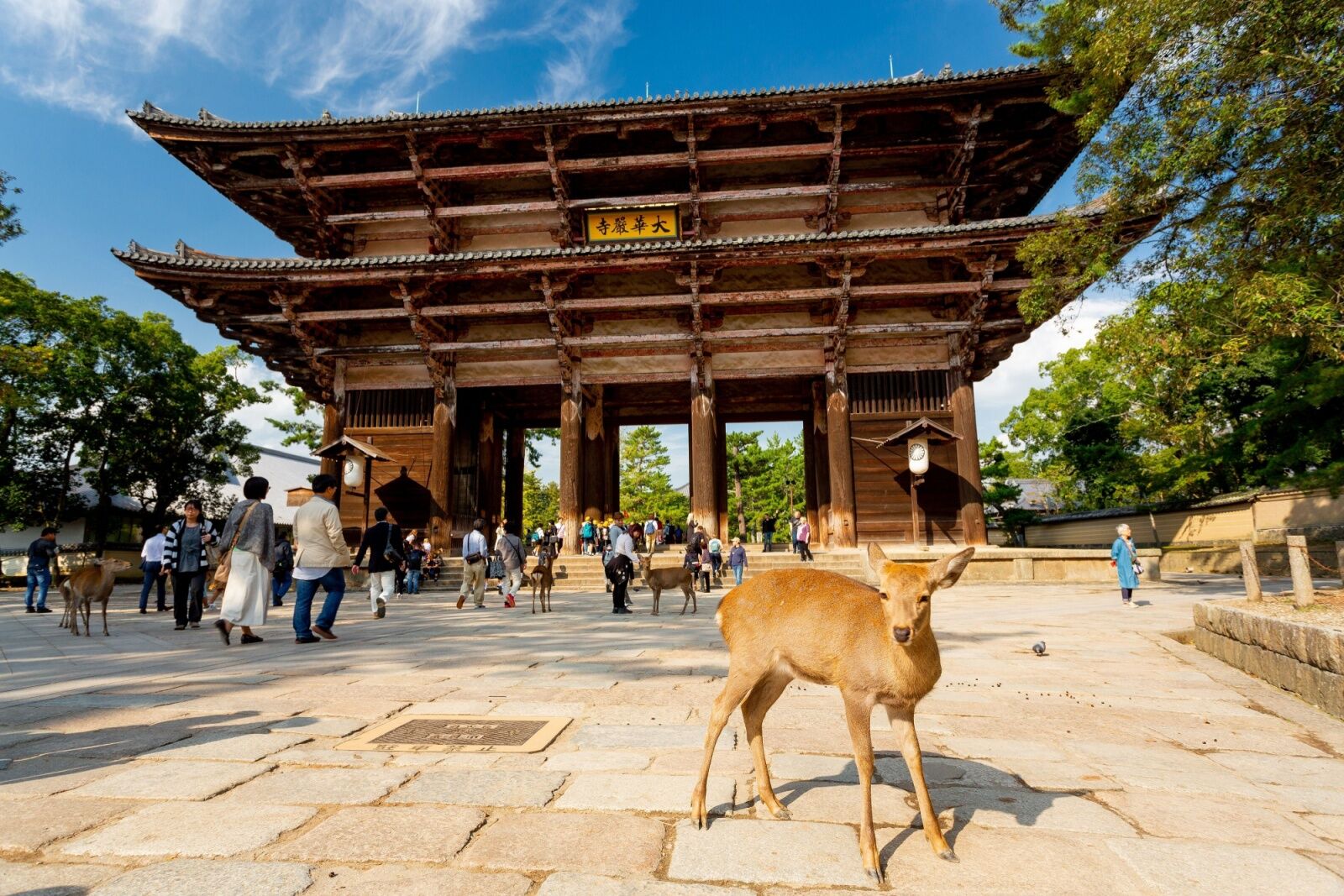

Nara refers both to the prefecture and its largest city, which was Japan’s first permanent capital, established in 710 CE. Many visitors to Tokyo or Osaka make day trips to Nara to visit the Great Buddha at Todai-ji Temple, but Nara is so saturated with history (as well as traditional artisan shops, charming towns, and excellent cuisine) that it’s best to try to spend at least two or three days there.

The most iconic image of Nara is the Great Buddha of Todai-ji Temple, one of the largest Buddhas in Japan. It was constructed in the eighth century from bronze, stands 15 meters high, and weighs approximately 500 tons. Look carefully at the statue’s pedestal to find etchings illustrating the various heavens and hells of Buddhist cosmology, including animals, angels, demons, and humans whirling through cycles of birth, death, and rebirth. Todai-ji is a skyscraper of cedar and hinoki wood, with much of its architecture — including the curved eaves, multi-tiered roofs, and large courtyards — inspired by Tang Dynasty China.

Deer in front of the Nandai-mon, or Great South Gate, leading to Todai-ji Temple in Nara. Photo: Florian Augustin/Shutterstock

Within walking distance of Todai-ji is Nara Park, encompassing a large swath of forest, a clutch of shrines, and more than 1,200 roaming deer. The deer are tame enough to pet and feed, and tradition holds that they’re messengers between humans and the Kami (Shinto gods). While it’s always best not to pet wild animals, many people do.

After visiting the temples, visitors with extra time should spend time wandering through narrow streets, charming craft shops, and the enticing restaurants of Naramachi, Nara’s old town. Nakagawa Masashichi Shoten is a two-story store selling artisan and local crafts, garments, and gourmet specialties; it’s an excellent shop for souvenirs and gifts. Visitors can also take part in a traditional wabi-cha tea ceremony at Nakagawa Masashichi Shoten. It lasts about an hour, leaving plenty of time to savor the ceremonial-grade matcha and gaze out onto the immaculate surrounding Zen gardens.

Where to stay in Nara

A private Onsen at FUFU Nara. Photo: FUFU Nara

Yukawa is a 300-year-old ryokan that could have been replicated from a Victorian-era British painter’s fantasy of Japan. Yukawa’s geothermal baths overlook unbroken stretches of forest, and the hotel’s interior is graced with priceless wall scrolls, ornately painted screens, and elegant flower displays following the strict rules of ikebana flower arranging. After deep post-onsen slumber, I spent the morning strolling through the town of Yoshino, a historical village renowned for its exceptionally beautiful cherry blossoms. Basho, one of Japan’s most celebrated poets, was so enamored with Yoshino that he returned to the town several times during his solitary wanderings across Japan.

FUFU Nara, designed by renowned architect Kengo Kuma, epitomizes omotenashi, traditional Japanese hospitality. Every detail of the property seemed meticulously considered, from the coveted whiskeys in the lobby bar to the herbal satchets to infuse in your private onsen to the yukata hanging in the closets.

FUFU Nara houses several upscale restaurants, and my favorite was the teppanyaki counter. Seated in front of a grill, you choose from locally sourced delicacies, the likes of wagyu, spiny lobster, or abalone, for the chef to cook á la minute. The menu includes French wine, rare whiskey, and Japanese craft beer to pair with charred beef and seafood. Imagine the Benihana of your childhood, but with Michelin-level glamour. ![]()

![[DEALS] iScanner App: Lifetime Subscription (79% off) & Other Deals Up To 98% Off – Offers End Soon!](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)