Did the Trump prosecutions backfire?

This story was originally published in The Highlight, Vox’s member-exclusive magazine. To get early access to member-exclusive stories every month, join the Vox Membership program today. Donald Trump’s return to the presidency will mark an end to eight years of his critics’ hopes that he could be taken down through the legal process. The Russia […]

This story was originally published in The Highlight, Vox’s member-exclusive magazine. To get early access to member-exclusive stories every month, join the Vox Membership program today.

Donald Trump’s return to the presidency will mark an end to eight years of his critics’ hopes that he could be taken down through the legal process.

The Russia investigation, four criminal prosecutions, and a conviction at trial on 34 felony counts ultimately did not dissuade voters from handing Trump another term in November.

So what did all those investigations and prosecutions of the president-elect amount to?

Some would argue that the answer is: nothing. Because voters ultimately shrugged off Trump’s legal woes, he won the election. This will let him end the two federal prosecutions of him and avoid consequences for the two state ones. Meaning: He’ll get off scot-free.

The outcome may even be worse than that. For years, many in the country’s liberal and centrist elite argued that these investigations were righteous attempts to hold a corrupt figure accountable for his rampant lawbreaking. They argued that Trump posed an imminent threat to democracy and that the best way to defend the rule of law was by thoroughly investigating and prosecuting him.

And yet the most salient legacy of the Trump cases may be that they’ve helped trap the country in a destructive tit-for-tat spiral of politicized lawfare, or legal warfare.

Trump now will take office far more embittered with the Department of Justice that indicted him — and perhaps more determined to weaponize that department against his opponents — than ever before. The investigations did not make Trump a corrupt person: He was pledging to send the DOJ after his political rivals before he was even elected in 2016. But his personal peril may have focused his resentment, so that he’ll be more hell-bent on making sure the department serves his whims.

Perhaps more consequentially, he’ll now have much more cover from the GOP. Republicans at all levels of the party have increasingly accepted Trump’s argument that he was being unfairly persecuted by Democrats and a politicized “deep state.” They’ve become polarized and radicalized against federal law enforcement institutions — and perhaps more likely to confirm nominees who would have seemed unthinkably extreme a few years ago.

It is far from clear that investigators could have followed some alternate path that would have avoided this outcome completely. A confrontation between Trump and the rule of law was likely inevitable as soon as he was first elected — he is who he is.

Investigators were regularly faced with the no-win choice between ignoring potential Trumpian wrongdoing, and thoroughly investigating in a way sure to invite attacks and reprisals. Letting real malfeasance, like Trump’s attempt to steal the 2020 election, go unpunished would have been galling.

But, as the saying goes, if you come at the king, you best not miss. They missed — and now the country will reap the consequences.

The threat to democracy: It’s time for some game theory

Many Democrats, and at least some among the country’s nonpartisan elite establishment, conceived of the threat to democracy in the past eight years this way: Donald Trump is an unethical, corrupt, and dangerous figure — possibly even a budding dictator — who poses grave threats to democracy, the rule of law, and the United States of America.

Therefore, the way to save the country was to stop Trump, either at the ballot box or by disqualifying him, either legally or in the eyes of the public. He could be expelled from politics through investigations, impeachment, prosecutions, removal from the ballot, or even imprisonment.

Of course, practically no one directly involved in the many investigations of Trump would publicly say their true motivation was to stop him from winning (one potential exception came in an FBI agent’s text to his affair partner). Many defenders of the investigations argue that they were simply an attempt to make sure Trump was not above the law, and that they wanted to prevent an obviously lawless person from endangering the country.

This way of thinking provides helpful moral clarity, but has inherent tensions. For instance: Are you truly standing up for democracy if, in effect, you’re trying to unseat the presidential election winner, or to prevent him from running again? Is there ever a risk that the line could be crossed — so that the threat to democracy would be coming from inside the house?

In a 2023 paper, Rachel Kleinfeld, a fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, pointed out the irony that many efforts to “save democracy” tend to loudly proclaim that their political opponents pose an existential threat to democracy. There are, Kleinfeld argued, a few problems with this.

First off, partisans tend to “overestimate the willingness of the other side to break democratic norms.” Second, this overestimation “makes them more likely to support or even take antidemocratic practices for their side.” And third, these efforts can end up deepening polarization and inviting reprisals, which puts democracy in more danger.

Kleinfeld’s paper brings to mind international relations models of how unwanted wars can start: a two-sided process involving a spiral of escalations, as well as perhaps some misperception and miscalculation.

Trump’s critics generally have a one-sided view of the threat to democracy: believing it comes entirely from Trump and the GOP, that Democrats and the Trump cases were righteous attempts to enforce the rule of law, rein in abuses of power, or save the country from a possible tyrant.

A two-sided view of the threat to democracy in the Trump era would look different. It’s time for some game theory:

- Back in 2016 and early 2017, investigators inclined to be suspicious of Trump thought it was plausible he was being blackmailed or bribed by Vladimir Putin — or that he was involved in the Russian government’s plot to hack and leak Democrats’ emails — and that he posed a serious and imminent threat to American national security.

- Trump was outraged by this and viewed it as a politicized plot against him and struck back, including by firing FBI Director James Comey, more intensely meddling in the Justice Department, and turning Republicans against the investigation

- Democrats and other Trump critics, outraged he seemed to be getting off the hook, intensified investigations against him elsewhere, vowing to bring him to justice if Democrats regained power

- Trump, fearing prosecution if he left office, stunningly escalated by trying to overturn Biden’s victory and stay in power. That is, his own fear of legal jeopardy may have made him more likely to abuse power.

- The attempt to steal the election cemented Democrats’ belief that Trump is a uniquely dangerous threat, and when he did leave office, they intensified efforts to prosecute him on both that and other matters.

- The prosecutions cemented Trump and his supporters’ belief that the deep state will stop at nothing to get him, and they vowed to dismantle the FBI and DOJ if he returned to power.

- Since Trump has won, some Democrats, fearing political targeting by his Justice Department, have called on Biden to issue broad preemptive pardons to Trump’s enemies — something that, if carried out, would only cement the right’s belief of a corrupt conspiracy to cover up Democratic wrongdoing.

I think both of these views are worth grappling with. My own view is somewhat of a mix of the two.

Our political system has gotten stuck in a harmful cycle of tit-for-tat lawfare and that certain Trump investigators have at times overreached. However, I also believe the threat to democracy comes primarily from Trump himself and would not be solved by Trump’s opponents deciding to stand down — to unilaterally disarm, as some might say.

A confrontation between Trump and investigators was probably inevitable

To show how difficult it is to avoid this downward spiral, it’s worth going through the various Trump investigations and assessing if there’s anywhere they went wrong, or anything they should have done differently.

The cycle started with the Russia investigation. But that investigation existed because Russian intelligence officers really did illegally hack Democrats’ emails and have them leaked during the 2016 campaign. Then, the FBI really did get a tip that a Trump campaign adviser was bragging about having inside knowledge about that hack. And various Trump advisers really were making shady-looking Russian contacts during the campaign.

Prosecutors did not find, in the end, any conspiracy between Trump’s team and Russia about the email hacks. But should they not have even looked? And when Trump fired Comey, citing a comically false justification, should everyone have just pretended there was nothing unusual about that?

Investigators could have avoided various missteps and controversies that eventually became public and spurred intense criticism from the right. But I don’t actually believe there was a way to do a halfway rigorous Russia investigation without making Trump furiously want to shut it down. The problem was that he did not believe he should be investigated at all.

That’s a problem because Trump and the people around him did so many things prosecutors thought were worth investigating. Beyond the Russia claims, there were the hush money payments to Stormy Daniels and others before the 2016 election, intelligence claiming that the Egyptian government sent $10 million to Trump’s campaign that same year, and reports of potential wrongdoing regarding Trump’s inauguration committee. (Federal prosecutors eventually abandoned all three probes without charging Trump.)

The idea that Trump mainly abuses power if he feels legal jeopardy is also questionable — indeed, the opposite could be true. I’ve always found it noteworthy that shortly after the Mueller investigation wrapped up and Trump’s legal jeopardy seemingly evaporated, he hatched his idea to try and hold back aid from Ukraine unless President Volodymyr Zelenskyy provided him with dirt on the Bidens — the idea that earned him his first impeachment.

So would freedom from investigations have incentivized Trump to behave better, or would it just have encouraged him to try to get away with more corrupt stuff?

Now, some reports did claim Trump’s fear of prosecution was weighing on him before the 2020 election — the New York Times reported Trump was concerned about “existing investigations in New York” as well as “the potential for new federal probes.” But it’s hardly clear that this was the decisive factor spurring him to try and steal the election: He may have done it anyway.

Trump was actually prosecuted for specific things. Were those prosecutions justified — or overreach?

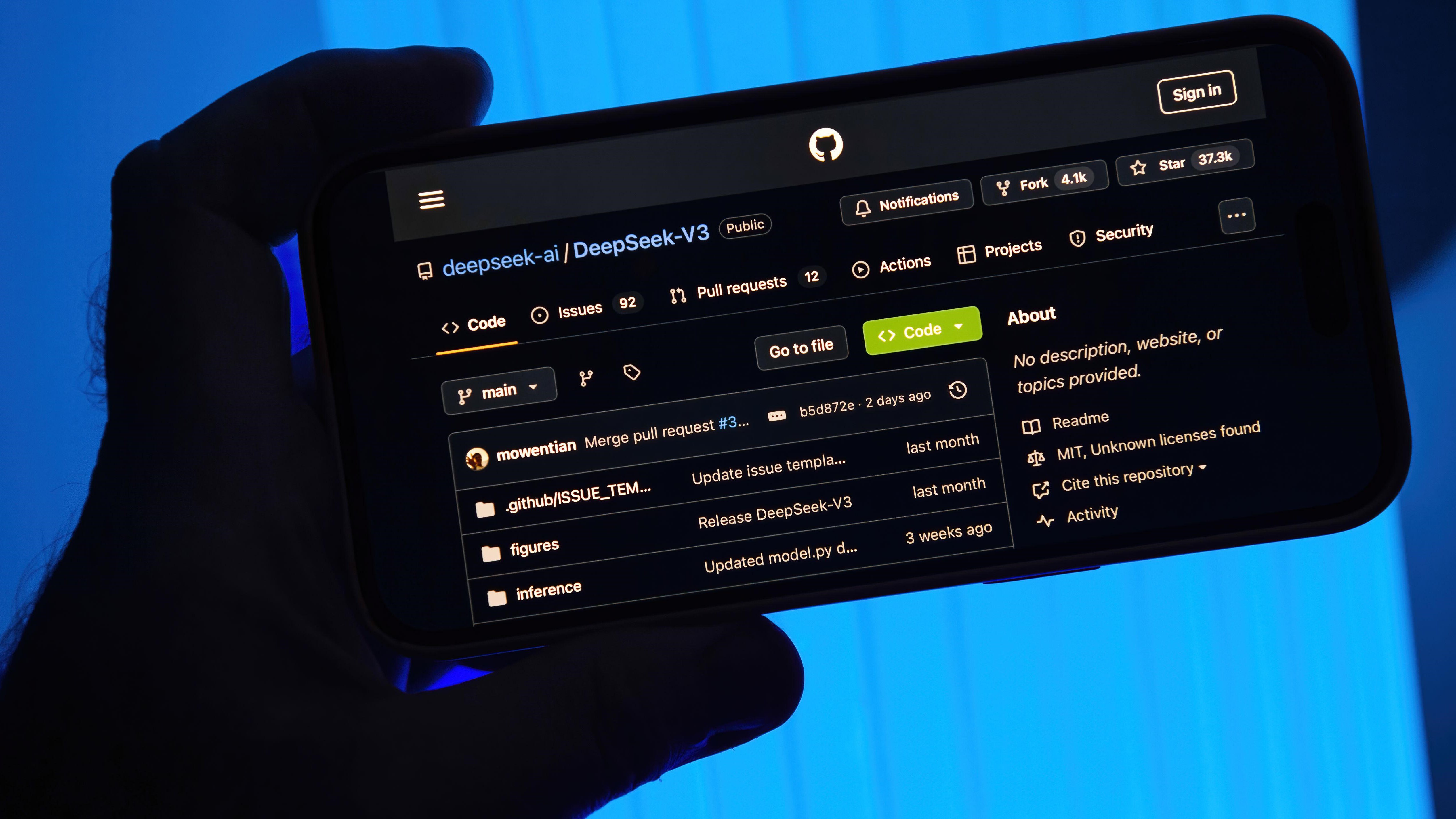

If Trump did try to steal the 2020 election in part due to fears of being prosecuted if he lost, those fears ended up being self-fulfilling — three of the four prosecutions he eventually faced were about actions he took after Election Day 2020. These are federal and Georgia state charges over his election-stealing effort, as well as federal charges over his refusal to return classified documents after leaving office. (I’ll address the fourth, the New York prosecution, further down.)

Regarding the classified documents strewn around-Mar-a-Lago: Trump pretty clearly seems to have violated the law. Some may argue that prosecutors should have continued negotiations with him over which documents he should give back rather than making the dramatic, headline-grabbing move of searching Mar-a-Lago. Perhaps the optics of other politicians like Biden having some classified documents stashed away were problematic in the court of public opinion. Ultimately, a Trump-appointed Florida judge bottled up the prosecution and it amounted to nothing.

Trump’s election-stealing attempt posed a different challenge to investigators: however appalling his conduct, there was no initial consensus that it actually was illegal. A situation like Trump’s attempt to stay in office had never occurred in US history and there was no clear precedent with which to ground this case.

Accordingly, Biden’s DOJ was hesitant to go after Trump for it. This reluctance lasted for about Biden’s first year in office, and outside criticism built over allegedly letting Trump off the hook. Word even leaked out that Biden himself was saying in private that he thought Trump should be prosecuted. (“I have never once — not one single time — suggested to the Justice Department what they should do or not do, relative to bringing a charge or not bringing a charge,” Biden later said publicly.)

Whether in response to the criticism or not, Biden’s DOJ came to embrace a legal theory in which Trump’s actions amounted to criminal conspiracy. This idea initially hinged on the idea that one part of the scheme — lists of “fake electors” — amounted to forgery of documents, though it broadened to other aspects of Trump’s conduct in special counsel Jack Smith’s eventual indictment.

But as I wrote at the time, the indictment was not so much clear proof that Trump’s conduct was indisputably criminal; it was effectively an attempt to set a new precedent that conduct like his should be considered criminal.

This sounded appropriate to me — politicians shouldn’t try to steal elections! But many on the right were less persuaded by this legal creativity. The skeptics included the six Republican appointees on the Supreme Court, who issued a ruling that effectively prevented the federal election case against Trump from happening this year. (Meanwhile, a case brought in Georgia by Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis used the legal theory that Trump’s attempt to steal the election was racketeering, but it got bogged down for separate reasons).

The New York case is the least defensible

And then there is New York — where the idea that investigators were high-mindedly trying to defend the rule of law regardless of politics is least persuasive. There, Democrats elected to top law enforcement positions spent years digging into Trump’s history and his company to search for charges that might stick to him. “We will use every area of the law to investigate President Trump and his business transactions and that of his family as well,” state Attorney General-elect Letitia James vowed in December 2018.

James’s office worked with Manhattan district attorney Cyrus Vance Jr., who in 2019 opened a criminal probe about the Stormy Daniels hush money, after federal prosecutors indicated they were no longer pursuing the case. Eventually, Vance put that aside in favor of probing the Trump Organization’s real estate valuation practices. He attempted to “flip” the company’s chief financial officer Allen Weisselberg against Trump by charging him with tax fraud. (Weisselberg eventually pleaded guilty and served a brief jail sentence but never provided bombshell cooperation implicating Trump.)

When Alvin Bragg succeeded Vance as district attorney in 2022, he wasn’t particularly impressed with the real estate valuation case and put a hold on it. This spurred the two top prosecutors on the case to resign in protest, which brought intense public criticism of Bragg for purportedly letting Trump off the hook.

Whether because of the criticism or not, Bragg’s team ended up returning to the matter of the hush money payments to Daniels. The payments had been made by Trump’s fixer Michael Cohen, and Trump later repaid Cohen for them — but, in internal company documents, the Trump Organization called these repayments legal expenses. Bragg’s indictment alleged that this amounted to felony falsification of business records.

As I wrote at the time, the Manhattan DA’s case always looked quite a bit to me like an attempt to “get Trump” for crimes to be determined later. It was a fishing expedition that lasted years, the charges were somewhat obscure and technical, outside analysis were skeptical of its legal theories, investigators were internally divided on the case’s strength, and those in charge of it had pretty obvious political motives (needing to win Democratic primaries in heavily Democratic territory).

But the New York charges did not succeed in sinking Trump; if they had any impact at all, it was the opposite. Before the indictment, Trump led his closest GOP primary rival, Ron DeSantis, by about 15 points in the polls — but just one week afterward, Trump’s lead skyrocketed to nearly 30 points as Republicans rallied around him. (His eventual conviction didn’t budge general election polls; ultimately, the public looked at this case, and yawned.)

When I’ve warned about the dangers that Trump will weaponize law enforcement against his political enemies, a common response from his supporters is: That’s already happened, to Trump, from Democrats. With the Russia probe, the election cases, and the classified documents case, I think it’s more complicated than that. But the New York case is the one where Trump’s argument that he was the victim of politicized lawfare is strongest.

Is there any way to get out of the spiral?

Even if one accepts the premise that we’ve gotten trapped in a cycle of politicized lawfare, it’s much harder to figure out how we escape it.

Kleinfeld, the democracy researcher, reviewed existing research about what makes people more or less likely to support antidemocratic ideas. “The only interventions that currently appear to have a valuable effect on antidemocratic attitudes,” she wrote, “focus on correcting the particular misbeliefs about the other side’s willingness to break democratic norms.”

That is: If you’re less likely to believe the other side presents a lawless threat to democracy, you’re less likely to embrace lawless practices from your own side.

But what if the other side does pose a threat?

Many of the Trump investigations and prosecutions were justified — either implicitly or explicitly — with the idea that Trump was a corrupt and dangerous figure posing grave threats to democracy and the rule of law.

There were always good reasons to worry about this. On the debate stage in October 2016, Trump told Hillary Clinton he’d appoint a special prosecutor to go after her. One week after being sworn in as president, Trump told FBI Director Comey that he wanted “loyalty.”

Not every fear about Trump was vindicated. Trump was not a deep-cover Russian agent. He did not actually manage to lock up his critics during his first term. Various guardrails of democracy constrained his worst impulses. Elections proceeded as scheduled.

But many fears about the threat he posed to democracy and the rule of law were proven right. Foremost among those was his attempt to steal the 2020 election, of course. But at other times in his first term, he repeatedly attempted to send the Justice Department after people he didn’t like. He tried to enlist the DOJ to help him steal the election. He has always wanted to weaponize the legal process against his (real or perceived) enemies. Just last month Trump filed a lawsuit over a poll he didn’t like.

So while mistakes were made in the Trump investigations, it’s hard for me to see why a more lenient approach from investigators, or a less confrontational approach from Democrats, would have alleviated Trump’s threat entirely.

Still, the real damage that eight years of investigations has wrought is the polarization that has occurred — as both Republican voters and elites have become increasingly polarized against the DOJ and the FBI, and increasingly willing to empower Trump to tear those agencies down.

And soon, we’ll find out just how justified those darkest fears about Trump’s intentions really are.