Contrails Are A Hot Topic, But What Is To Be Done?

Most of us first spot them as children—the white lines in the blue sky that are the telltale sign of a flight overhead. Contrails are an instant visual reminder of …read more

Most of us first spot them as children—the white lines in the blue sky that are the telltale sign of a flight overhead. Contrails are an instant visual reminder of air travel, and a source of much controversy in recent decades. Put aside the overblown conspiracies, though, and there are some genuine scientific concerns to explore.

See, those white streaks planes leave in the sky aren’t just eye-catching. It seems they may also be having a notable impact on our climate. Recent research shows their warming effect is comparable to the impact of aviation’s CO2 emissions. The question is then simple—how do we stop these icy lines from heating our precious Earth?

But How?

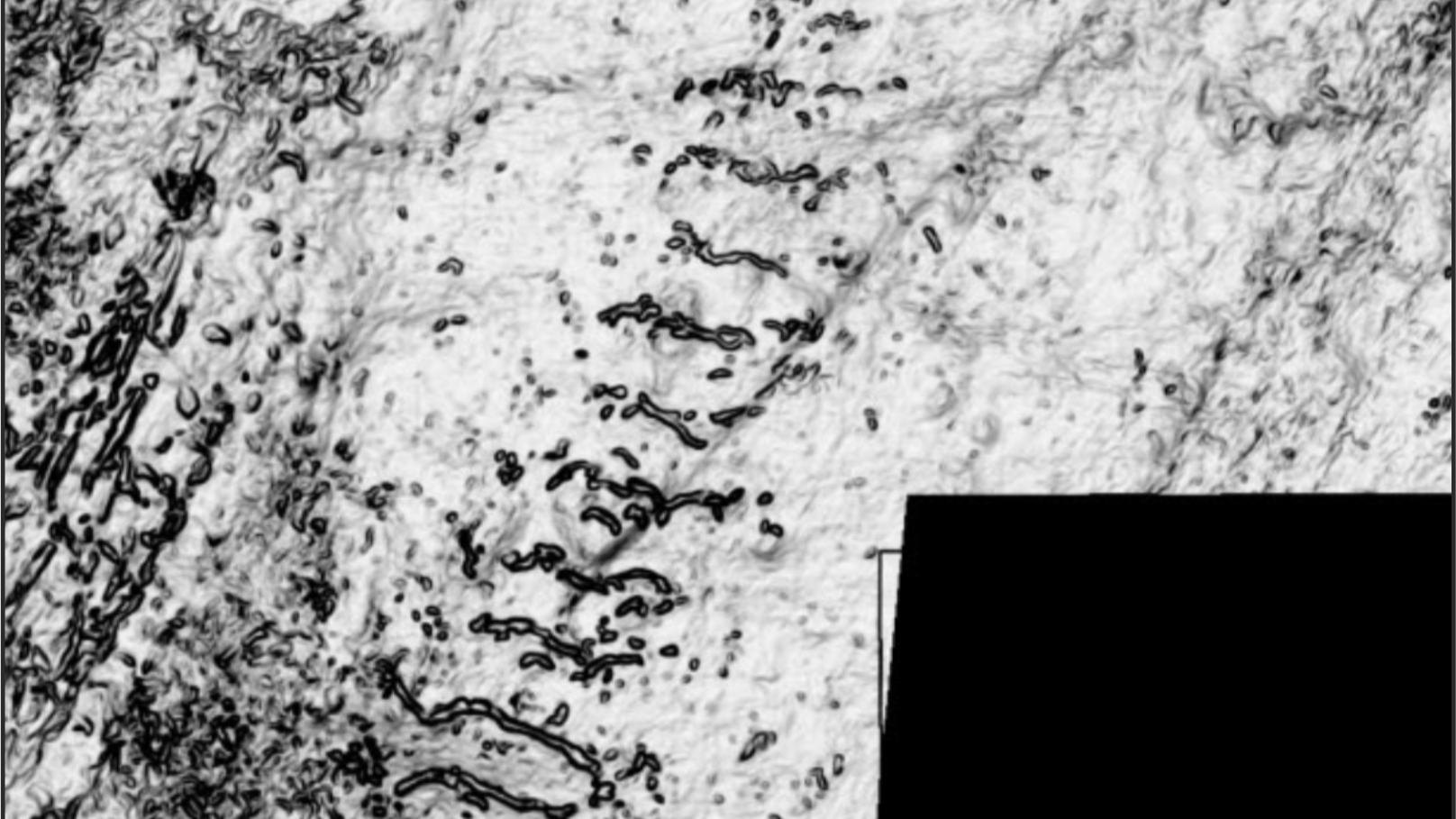

The name contrails is a portmanteau of “condensation trails,” which tells you everything you need to know. Those white streaks form when aircraft fly through cold, humid areas of the atmosphere. They come about when water vapor mixes with tiny particles of soot and sulfur in the aircraft’s exhaust, which act as nucleation points for forming water droplets. These then tend to freeze in low temperature conditions, creating icy particles behind the aircraft. The result? The telltale trail in the sky.

Due to the chemical vagaries of combustion, aircraft exhaust pretty much contains all the ingredients for contrail production—primarily water vapor and tiny particulates. However, those alone aren’t enough to produce a bright and lingering contrail. Some contrails may only last a few seconds, or maybe a few minutes, in moderately cool zones of the atmosphere. However, in places where it gets particularly cold and humid, it’s possible for an aircraft to leave contrails that last for hours, slowly spreading out until they become many kilometers wide. Under these conditions, they functionally increase the level of cloud cover in the atmosphere.

The Problem

Unfortunately, contrails aren’t just pretty lines in the sky. Scientists have found they also have an impact on the climate—and not in the direction we’d like. Unfortunately, contrails tend to have a warming effect. While they increase the amount of sunlight reflected away from Earth, they ultimate trap more heat in the atmosphere than they bounce away.

It might sound like a minor thing, but the science suggests their warming impact is likely larger than that of fossil fuel emissions from global aviation operations. One study performed in 2018 suggested that contrails are doing more to heat up the Earth than all the CO2 emitted by aviation since 1940. The science is clear – these artificial clouds are a serious climate concern.

There is hope for tackling this icy problem, however. As most of us have noticed, not every plane leaves a bright, long lasting contrail. That’s because atmospheric conditions have to be within a certain range to produce them. Fly in warmer, less humid air, and your contrails won’t last as long—nor do as much harm to the climate.

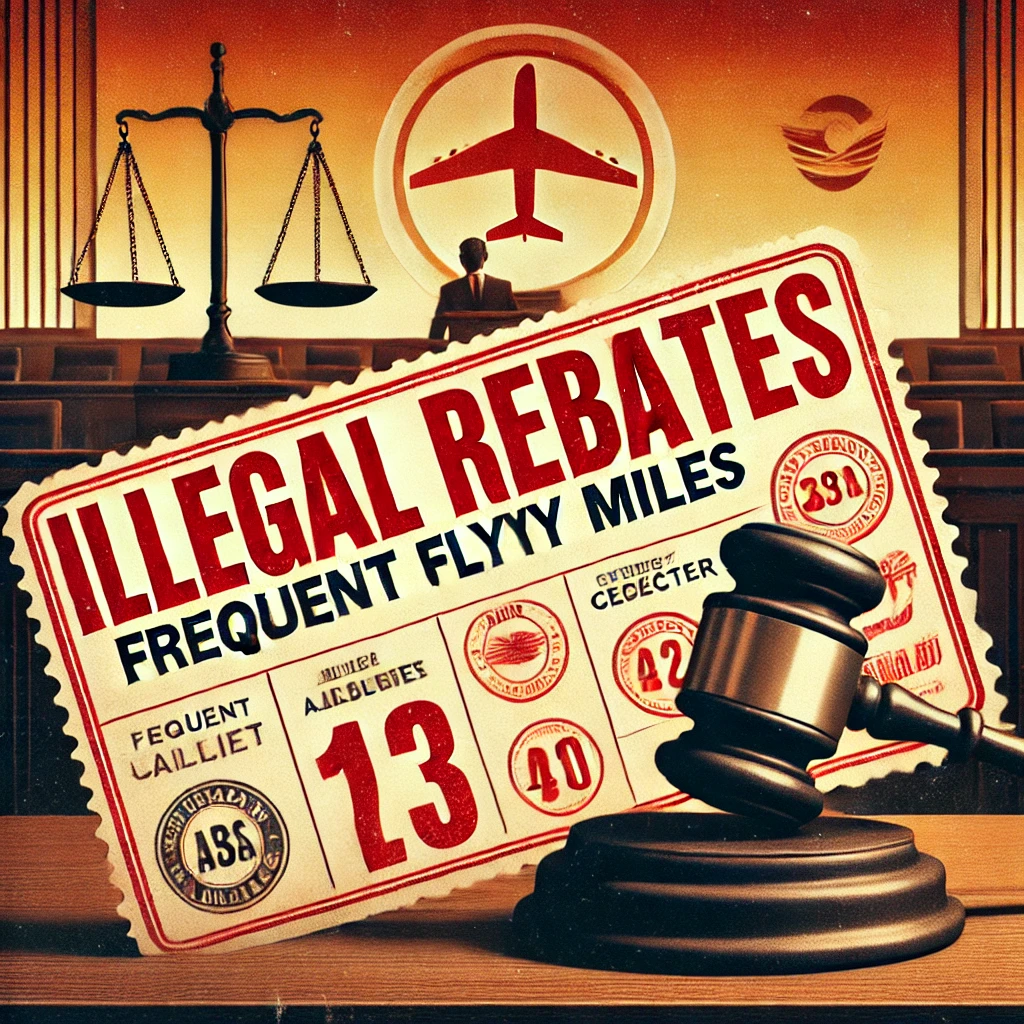

As it turns out, less than 3% of global flights generate 80% of contrail warming. The effect is particularly pronounced in regions like North America, Europe, and the North Atlantic, where high-altitude flights are common. Night flights also cause the most warming, because the clouds are just trapping heat. Daytime flights create less damaging contrails because they reflect some sunlight to offset the heat they’re trapping on Earth.

The good news is that relatively simple solutions exist. By making minor adjustments to flight paths – climbing or descending slightly to avoid the cold, humid atmospheric layers where contrails form – airlines can significantly reduce their climate impact. In a 2023 trial, tests by American Airlines and Google showed that it was possible to cut contrail formation by 54% with only a 2% increase in fuel use. With only some flights having to adjust their routes to reduce contrails, the effect could be as little as an 0.3% increase in fuel burn across an airline’s fleet. In fact, one study suggests that the benefits of producing less contrails would be 100 times greater than the penalty of added greenhouse gas emissions from the greater fuel burn. Cost-wise, estimates suggest avoiding contrails would add just €3.90 to a Paris-New York ticket or €1.20 to a Barcelona-Berlin flight.

The aviation industry now faces a clear opportunity: by targeting the small number of flights causing most contrail warming, they could make a major dent in their climate impact at minimal cost. With appropriate weather forecasting and flight planning, contrail avoidance could be one of aviation’s most cost-effective climate solutions.

It’s not an instant solution—there is still a great deal of work to be done before this is a routine practice in the industry. Ultimately, more fuel burn will still cost airlines money, as will the administrative overhead of predicting pro-contrail conditions and tasking aircraft to avoid them. Regardless, addressing contrails offers a smart, immediate way to reduce aviation’s contribution to global warming. The science is solid, the solutions are available, and the costs are theoretically manageable. The next step is putting this knowledge into action—the question remains as to which airlines lead the charge.

![[DEALS] iScanner App: Lifetime Subscription (79% off) & Other Deals Up To 98% Off – Offers End Soon!](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)