Blockchain projects fight for 23andMe user data amid bankruptcy

DNA testing firm 23andMe is bankrupt, and now the genomic data of its 15 million users is up for sale to the highest bidder. Could that data end up on the blockchain?The company announced on March 23 that it had filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection and that its CEO, Anne Wojcicki, had stepped down. The announcement sent waves of concern among 23andMe’s customers, many of whom are now scrambling to delete their data from the service.Privacy advocates and government officials alike have weighed in on the situation, urging users to download and then delete their data ASAP. The sense of urgency increased on March 26 when a judge gave 23andMe the official stamp of approval to sell user data. But there is still the question of where these users should move their data and whether there is ultimately a better alternative.In the wake of the bankruptcy, blockchain advocates have seized the opportunity to make the case that DNA is better off on the blockchain — whether directly stored on the servers of a decentralized network or using some elements of Web3 technology on the back end. The promise of a more private 23andMe, where users control their own data, is alluring to many — yet actually bringing the world of DNA sequencing onto the blockchain is not without its own unique challenges.23andMe’s complicated privacy history23andMe may be most known for selling DNA testing kits and offering ancestry and health reports, but its core business model is actually centered around selling its customers' genetic data to pharmaceutical companies and other researchers.The company’s privacy policy states that it will only share a user’s DNA with a third party if the user grants permission. Around 80% of its users ultimately opt into this agreement. 23andMe also claims that any user information is anonymized before being shared, though it’s not inconceivable that someone’s unique genetic data could still be linked back to them.A December 2024 study by data removal service Incogni found that 23andMe’s privacy policy was actually one of the strongest among its competitors. Critically, however, the agreement also states that user data can be sold or transferred if the company is acquired — and the new owner may not have the same privacy policy.How DNA testing services use genetic information. Source: IncogniDarius Belejevas, head of Incogni, told Cointelegraph that customers give their genetic data to companies like 23andMe under the assumption that it will be protected under the privacy terms they agreed to. “A bankruptcy sale fundamentally alters the terms of that agreement, potentially exposing their most sensitive biological information to use by the highest bidder,” he said.“Yet again, we see a regulatory gap in the data collection industry, which, in this case, will likely leave 23andMe users never knowing what really happens with their physical samples and sensitive information.”Privacy policy concerns aside, 23andMe has also faced data leaks. In 2023, hackers stole ancestry data for about 6.9 million users — roughly half of its entire customer base at the time. What was particularly concerning was that the hack may have specifically targeted users of Ashkenazi Jewish and Chinese descent.A user of an online forum claims to be selling stolen 23andMe data in October 2023. Source: ResecuritySecurity experts have warned that stolen genomic information could potentially be used to carry out identity theft or even design targeted bioweapons. Back in July 2022, US lawmakers and military officials issued a warning at the Aspen Security Forum that the data held by DNA testing services — specifically calling out 23andMe — were potential targets for foreign adversaries who want to develop such bioweapons.“There are now weapons under development, and developed, that are designed to target specific people,” said Representative Jason Crow, a Democrat from Colorado who sits on the House Intelligence Committee. “That's what this is, where you can actually take someone's DNA, you know, their medical profile, and you can target a biological weapon that will kill that person.”Putting 23andMe on the blockchainPutting DNA on the blockchain is not a novel idea; Genecoin pitched it as early as 2014. But 23andMe’s bankruptcy is making headlines, and several blockchain projects are capitalizing on the momentum to make their respective pitches for why they offer a better alternative than 23andMe.At least four potential buyers have publicly declared their interest in 23andMe, and one of them is the Sei Foundation — the organization dedicated to advancing the Sei blockchain. The exact mechanics of how the foundation would bring 23andMe onto the blockchain are not entirely clear, but it reiterated on March 31 that it would ensure “one of the nation’s most valuable assets - the health of its people, survives on chain.”Source: SeiPhil Mataras, founder of the decentralized cloud network AR.IO — which is built atop Arweave — said that the move was a “f

DNA testing firm 23andMe is bankrupt, and now the genomic data of its 15 million users is up for sale to the highest bidder. Could that data end up on the blockchain?

The company announced on March 23 that it had filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection and that its CEO, Anne Wojcicki, had stepped down. The announcement sent waves of concern among 23andMe’s customers, many of whom are now scrambling to delete their data from the service.

Privacy advocates and government officials alike have weighed in on the situation, urging users to download and then delete their data ASAP. The sense of urgency increased on March 26 when a judge gave 23andMe the official stamp of approval to sell user data. But there is still the question of where these users should move their data and whether there is ultimately a better alternative.

In the wake of the bankruptcy, blockchain advocates have seized the opportunity to make the case that DNA is better off on the blockchain — whether directly stored on the servers of a decentralized network or using some elements of Web3 technology on the back end.

The promise of a more private 23andMe, where users control their own data, is alluring to many — yet actually bringing the world of DNA sequencing onto the blockchain is not without its own unique challenges.

23andMe’s complicated privacy history

23andMe may be most known for selling DNA testing kits and offering ancestry and health reports, but its core business model is actually centered around selling its customers' genetic data to pharmaceutical companies and other researchers.

The company’s privacy policy states that it will only share a user’s DNA with a third party if the user grants permission. Around 80% of its users ultimately opt into this agreement. 23andMe also claims that any user information is anonymized before being shared, though it’s not inconceivable that someone’s unique genetic data could still be linked back to them.

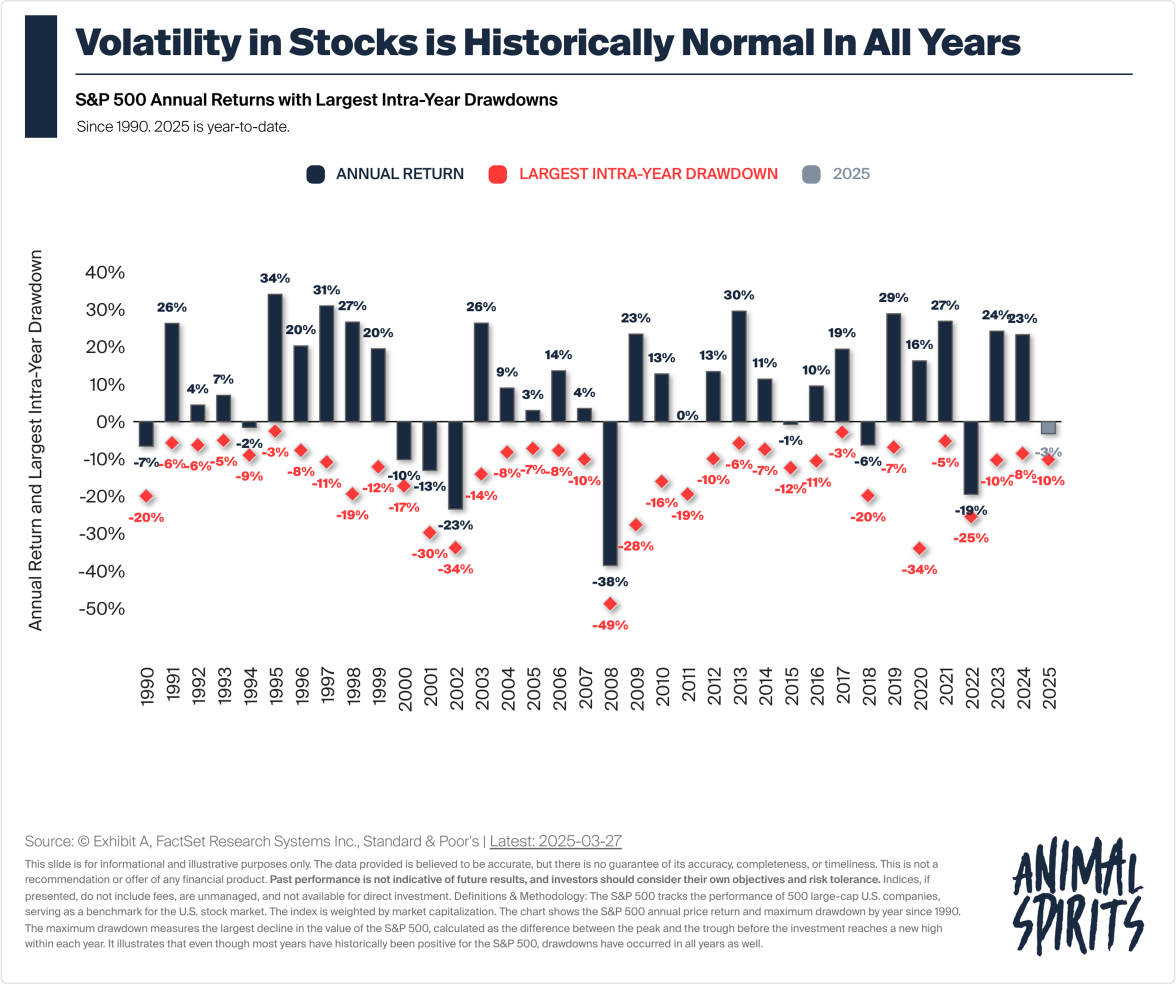

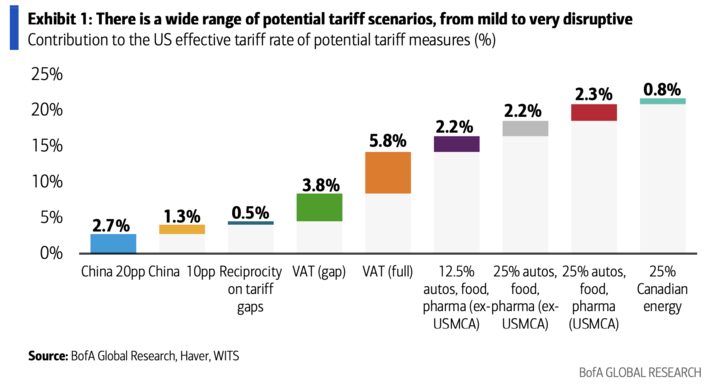

A December 2024 study by data removal service Incogni found that 23andMe’s privacy policy was actually one of the strongest among its competitors. Critically, however, the agreement also states that user data can be sold or transferred if the company is acquired — and the new owner may not have the same privacy policy. How DNA testing services use genetic information. Source: Incogni

Darius Belejevas, head of Incogni, told Cointelegraph that customers give their genetic data to companies like 23andMe under the assumption that it will be protected under the privacy terms they agreed to. “A bankruptcy sale fundamentally alters the terms of that agreement, potentially exposing their most sensitive biological information to use by the highest bidder,” he said.

“Yet again, we see a regulatory gap in the data collection industry, which, in this case, will likely leave 23andMe users never knowing what really happens with their physical samples and sensitive information.”

Privacy policy concerns aside, 23andMe has also faced data leaks. In 2023, hackers stole ancestry data for about 6.9 million users — roughly half of its entire customer base at the time. What was particularly concerning was that the hack may have specifically targeted users of Ashkenazi Jewish and Chinese descent. A user of an online forum claims to be selling stolen 23andMe data in October 2023. Source: Resecurity

Security experts have warned that stolen genomic information could potentially be used to carry out identity theft or even design targeted bioweapons. Back in July 2022, US lawmakers and military officials issued a warning at the Aspen Security Forum that the data held by DNA testing services — specifically calling out 23andMe — were potential targets for foreign adversaries who want to develop such bioweapons.

“There are now weapons under development, and developed, that are designed to target specific people,” said Representative Jason Crow, a Democrat from Colorado who sits on the House Intelligence Committee. “That's what this is, where you can actually take someone's DNA, you know, their medical profile, and you can target a biological weapon that will kill that person.”

Putting 23andMe on the blockchain

Putting DNA on the blockchain is not a novel idea; Genecoin pitched it as early as 2014. But 23andMe’s bankruptcy is making headlines, and several blockchain projects are capitalizing on the momentum to make their respective pitches for why they offer a better alternative than 23andMe.

At least four potential buyers have publicly declared their interest in 23andMe, and one of them is the Sei Foundation — the organization dedicated to advancing the Sei blockchain. The exact mechanics of how the foundation would bring 23andMe onto the blockchain are not entirely clear, but it reiterated on March 31 that it would ensure “one of the nation’s most valuable assets - the health of its people, survives on chain.” Source: Sei

Phil Mataras, founder of the decentralized cloud network AR.IO — which is built atop Arweave — said that the move was a “flashy, but exciting prospect” in comments shared with Cointelegraph. “The data would be more secure and tamper-resistant than any other kind of centralized data storage solution.”

AR.IO has itself been pushing for 23andMe users to download their data and move it over to the ArDrive decentralized storage solution, which has published a step-by-step guide explaining how to upload the data to an encrypted drive.

“This is something you can do right now, and then you won’t have to even worry about what will happen to your data, since it will no longer be in the 23andMe database,” said Mataras.

Blockchain project Genomes.io, which describes itself as “the world’s largest user-owned genomics database,” has seen new users flocking to the platform since 23andMe’s bankruptcy. “Hundreds of new users per week are joining us,” its CEO, Aldo de Pape, told Cointelegraph.

According to de Pape, “This is a clear use case for decentralized technology to improve a process that has been flawed from the beginning, and which is this essence of bringing data sovereignty back to individuals, giving the health information back to an individual, making sure that the owner and the health data are one.”

Genomes.io uploads users’ genomic data into what it calls “vaults,” which are end-to-end encrypted so that only the user holds the private keys needed to access the data. This also means that users' DNA will still be secured if the company is ever hacked or sold.

Users can then opt into specific studies on a case-by-case basis, and they get paid in the project’s native token when their data is used.

Related: Stop giving your DNA data away for free to 23andMe, says Genomes.io CEO

Another solution, GenoBank, has an alternative approach: tokenizing genetic information onchain as “BioNFTs.” The company offers DNA testing kits linked to non-fungible tokens that are self-custodied by the customer, meaning they can have their DNA sequenced anonymously.

“What if this moment of disruption could actually become a catalyst for positive change?” asked its CEO, Daniel Uribe, in a March 24 blog post. Much like Genomes.io, Uribe laid out a vision where everyone owns their data, controls who accesses it, captures its value and maintains privacy.

“This isn’t science fiction. The technology exists today.”

Blockchain comes with its own concerns

Despite the current hype around bringing blockchain to DNA, there are still challenges in doing so, and decentralized solutions offer their own set of potential risks.

If a customer misplaces the private keys to their genomic data, there is only so much any project or company can do to help them. Perhaps more terrifying is the idea of a user having their private keys hacked and their genomic data stolen.

De Pape said that Genomes.io, for its part, will work with customers to secure their vaults if their private keys are compromised, although they are unable to actually unlock a user’s vault.

Then there are additional privacy concerns at the laboratory level. Even if the final data is stored in the most private, secure manner possible, the sequencing laboratories themselves may not follow the same strict guidelines.

In terms of uploading DNA data directly to the blockchain, there could be an astronomical cost associated. A raw whole genome sequencing file a laboratory generates can be up to 30 GB. This means uploading the raw files for 15 million customers — the total number of people who have given their DNA to 23andMe — to a decentralized storage solution like Arweave would cost upward of $492 million as of April 1.

450,000 TB of raw DNA data would cost nearly half a billion dollars to upload to Arweave. Source: Arweave Fees

“Don't upload it [DNA] to the blockchain. That is the biggest mistake you could make,” argued de Pape. In addition to the cost, he said there are privacy concerns.

Blockchain, more often than not, is a public space, right? So, even if you put it on the blockchain, it doesn't mean that it's entirely private to you. There is a track record of you uploading the data there.

Finally, regulations add another layer of complexity to the matter. A 2020 study written in part by GenoBank’s Uribe found that regulatory frameworks like the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation, which sets strict guidelines for the handling of user data, have “generated some challenges for lawyers, data processors and business enterprises engaged in blockchain offerings, especially as they pertain to high-risk data sets such as genomic data.”

So, while blockchain certainly offers several advantages over centralized companies like 23andMe, it’s no panacea, and it may not be for everyone.

But regardless of where users choose to move their data, the message from privacy advocates and security experts remains clear: Don’t leave it with 23andMe.

Magazine: Crypto fans are obsessed with longevity and biohacking: Here’s why