AI agents are here. How afraid should workers be of losing their jobs?

Nearly one-third of workers already think that AI will lead to fewer jobs.

At Mobile World Congress, the telecom industry trade show held each March in Barcelona, AI agents were everywhere. Or rather, signs touting AI agents were everywhere. At the Google Cloud stand, telecom execs could watch demos showcasing how easily companies can build custom AI agents. At Microsoft’s stand, it was the same story. Qualcomm’s highlighted its “on-device agentic AI.”

It was a similar scene in January at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland—where signs pitching tech companies’ “agentic AI” offerings practically obscured the view of the surrounding snowcapped mountains. In fact, almost every place tech companies come to market their wares these days turns into an AI-agent fest.

There’s simply no buzzier topic in tech and business right now. AI agents are supposed to be what finally delivers AI’s long-promised productivity gains. It’s still early days, and businesses are being cautious, partly because AI agents carry more risks than other AI products. But if deployment ramps up rapidly, as many analysts expect, AI agents could radically transform how people work—and possibly lead to millions of jobs being cut.

But what are AI agents, and is the hype around them deserved? For starters, there is no agreed-upon definition of an AI agent—which is convenient if you want to claim to be selling one. But generally, it’s an AI-powered system that can complete tasks using other software tools. These systems have a generative-AI model at their core, but they can do more than the AI model can in isolation. A gen-AI model may be able to suggest an itinerary for an upcoming vacation. An AI agent could do that, too, but then actually make the bookings and reservations for you. This is obviously a more difficult task that involves multiple steps and use of the internet—and, to do well, quite a bit of reasoning.

This kind of automation is a perennial C-suite fever dream. Over the past decade, companies embraced “robotic process automation,” or RPA. This was software that could automate repetitive tasks, such as cutting and pasting between database programs. But traditional RPA systems are inflexible and unable to deal with exceptions, and can usually handle only one narrow task. RPA didn’t deliver what businesses wanted, says Amit Zavery, president of business software company ServiceNow, which is betting big on agents. He says agentic AI is different: “It can be flexible and adapt to how businesses want to operate.”

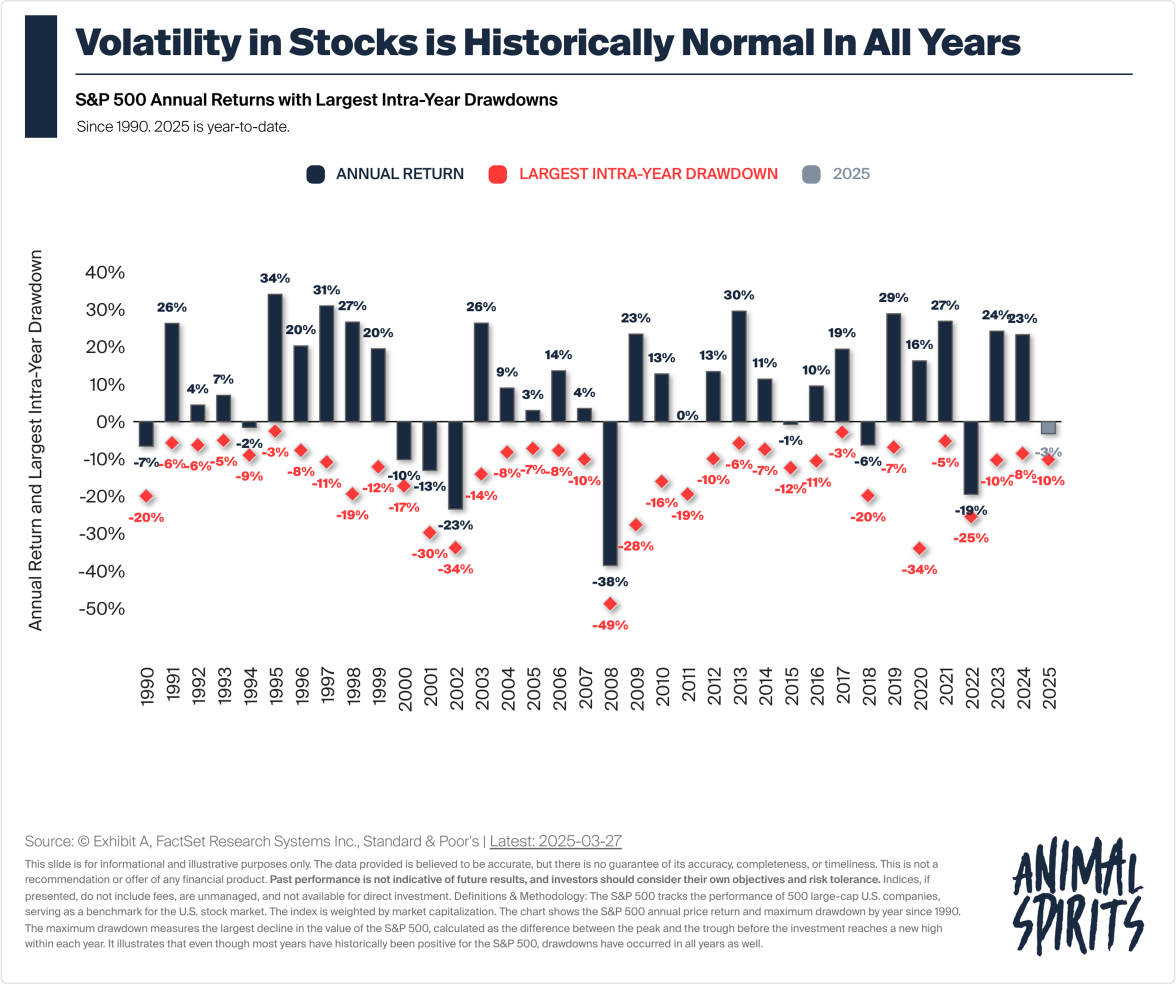

The U.S. market for AI agents is expected to reach $7.6 billion this year, according to Grand View Research, and that figure is growing at 46% annually. But those numbers likely underestimate the total impact. Consultants at McKinsey say AI could eventually unlock as much as $4.4 trillion in annual corporate productivity gains—with much of that coming from agentic AI.

For the moment, however, adoption remains nascent. “The AI-agent discussion is a mix of hype and real technical progress,” says Ruchir Puri, chief scientist of IBM Research. Meanwhile, Craig Le Clair, an analyst at research firm Forrester and the author of Random Acts of Automation, a book about the coming world of AI agents, says there are many “agent-ish” offerings, but few are truly autonomous agents that can adjust their approach to a task on the fly in response to changing conditions.

For now, agents are mostly being used for customer service and resolving internal IT support requests. They’re not yet good enough, however, to fully automate tasks like writing and debugging software, Puri says.

Because agents can take action, such as managing critical databases and engaging in financial transactions, the stakes are high if things go wrong. Big companies are therefore cautious about embracing the technology.

Still, agents are creeping into many domains—from helping onboard new employees to assisting lawyers to find and update language in contracts.

In a pilot project, McKinsey built an AI agent using Microsoft’s Copilot Studio software that can monitor an email address for incoming project proposals from potential clients. When one arrives in the inbox, the agent automatically assesses the job, estimating the staffing requirements, time to completion, and budget. It even suggests which available consultants should do the job. A human still must check what the agent produces, of course, but the technology has cut the time required to scope out a project from 20 days on average to just two days.

Double Agent

Spending on AI agents is soaring, but many fear they will kill jobs

32%Share of workers who believe AI will lead to fewer jobs

$7.6 billionExpected U.S. spending on AI agents this year

Sources: Pew Research Center; Grand View Research

What impact will AI agents have on workers? “I think it will be really disruptive,” Le Clair says. He knows of one Netherlands-based insurance company that had 15 contractors in Bulgaria helping to process claims-related emails. The contractors determined whether an email was about a new claim or an existing one, and made sure any information, including attachments, was uploaded to the appropriate databases. AI agents now do this work—and the company fired all the Bulgarian contractors.

But such cases may be the exception, at least for now. A recent study by two senior Bank for International Settlements advisors found AI agents underwhelming. While able to perform narrow tasks well, “they lack the self-awareness to know when they have gone wrong and change course in light of evidence,” the researchers wrote. People make mistakes, too, but they’re better at spotting and correcting their errors.

Of course, AI companies are racing to overcome these limitations. The new wave of reasoning models from the likes of OpenAI, Anthropic, Google’s DeepMind, and Chinese startup DeepSeek excel at making step-by-step plans and have some ability to reflect on these plans and make corrections. Adam Evans, the executive vice president heading up Salesforce’s AI efforts, says its latest AI agents, released in March, are starting to incorporate some reasoning capabilities. The company is also working on ways to help businesses orchestrate multiple agents to handle more complex tasks.

So, while most of our jobs are probably safe for the next year or two, we may all soon find ourselves shouting that old Hollywood shibboleth—“Call my agent!”—to renegotiate our employment contracts.

This article appears in the April/May 2025 issue of Fortune with the headline "AI agents are here. How afraid should workers be?"

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com