Yields just hit peak housing bubble levels. Get ready for a world of higher borrowing costs

A ballooning deficit and higher inflation could keep long-term interest rates elevated.

- Long-term interest rates have mostly been in steady decline since the mid-1980s thanks to low inflation and the supremacy of the U.S. dollar. Deficit concerns and a slowdown in global trade, however, might continue exerting upward pressure on Treasury yields.

Proposed tax cuts in the GOP’s “big, beautiful” bill have investors dumping Treasuries like it’s 2007. This time, however, the recent spike in long-term bond yields might be less of a momentary uptick than a sign of what’s to come for American borrowers.

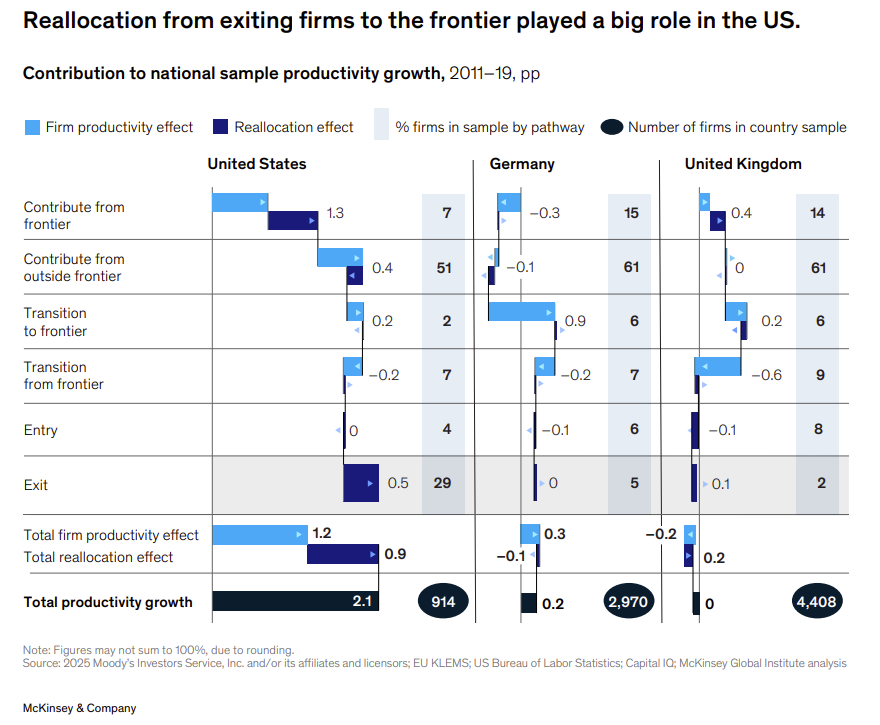

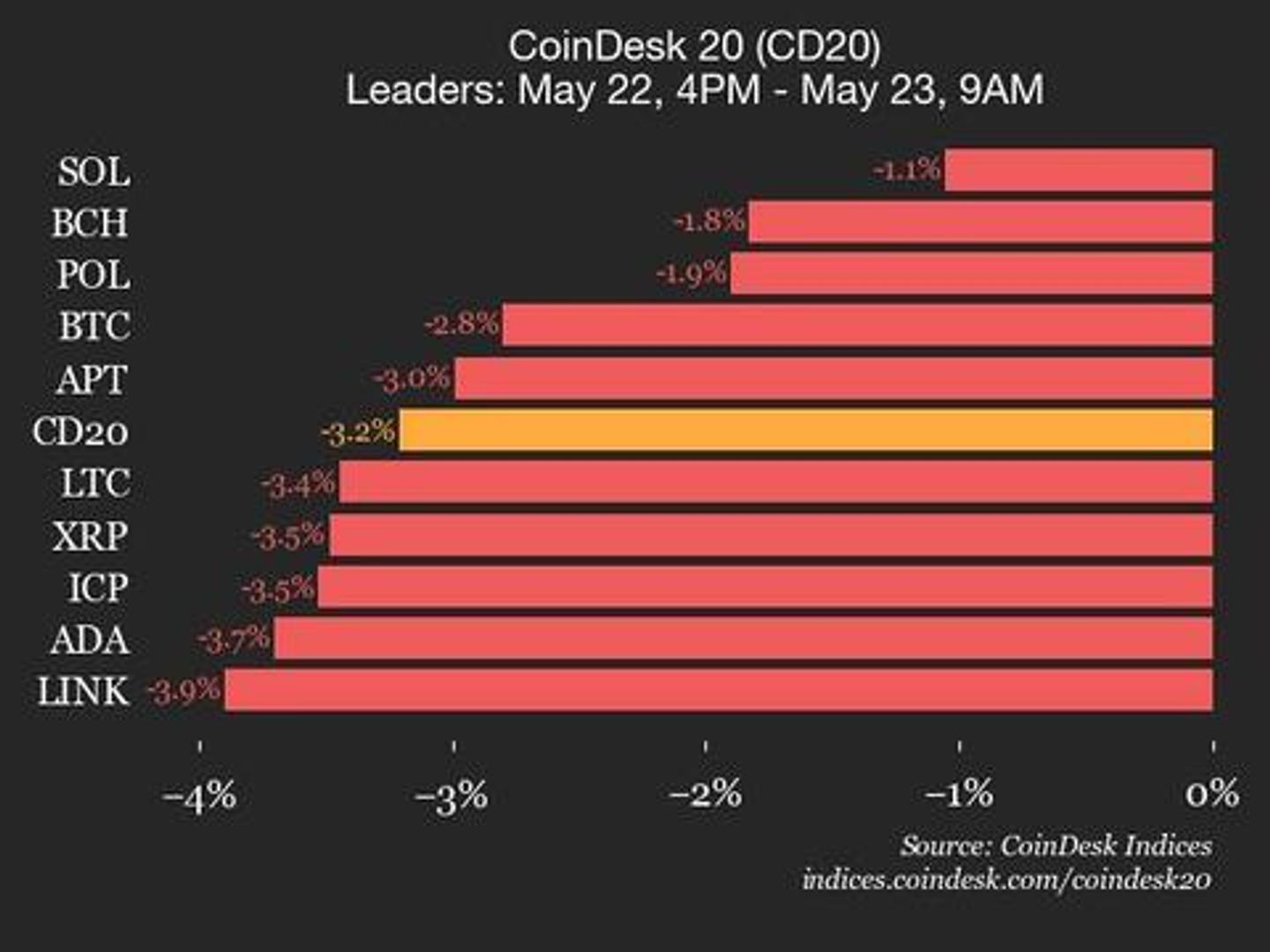

Take the 10-year Treasury yield, the benchmark for mortgages, loans to small businesses, and other common types of consumer and corporate borrowing. As the chart below shows, it has mostly been in steady decline since the mid-1980s, despite brief surges when the Federal Reserve raised interest rates before the Global Financial Crisis and after inflation surged following the COVID-19 pandemic.

But Jim Caron, chief investment officer for the portfolio solutions group at Morgan Stanley Investment Management, doesn’t see rates coming back down to historic lows.

“Get used to higher yields,” he told Fortune. “I mean, we have to get used to a steeper [yield] curve, and we have to get used to inflation not sitting below target for an extended period of time.”

Voters fed up with rising prices helped hand Donald Trump a second stint in the White House, and the president has pledged to lower borrowing costs for Americans. Despite his repeated criticism of Fed Chair Jerome Powell and the central bank for holding interest rates steady, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has said the Trump administration is focused on seeing the free-floating 10-year yield decline.

The president’s tariffs and push for tax cuts, however, have stoked fears about an inflation resurgence and a ballooning federal deficit, causing rates to jump. The 30-year Treasury yield closed above 5% Wednesday for the first time in nearly two years, hitting its highest level since the spring of 2007. The yield on the 10-year, meanwhile, briefly rose above 4.6%.

“There’s an additional risk premium that’s being attached to Treasury yields right now,” Caron said, “for good reason.”

Tariffs, tax cuts push yields higher

Yields first moved higher after the pandemic as the Fed raised interest rates to fight inflation, pushing bond yields up as the return on existing bonds became less attractive relative to new debt. The central bank then finally began cutting rates last year as price growth eased, and traders initially expected more of the same this year.

Powell, however, has made clear he and his colleagues are waiting for clarity on how tariffs impact the economy before making a move.

“Markets are starting to reprice what the Fed is going to do here in the near term and what the Fed might potentially do in the long term,” Matt Sheridan, lead portfolio manager for income strategies at AllianceBernstein, told Fortune.

Caron, meanwhile, doesn’t see tariffs causing a recession, which would presumably make the Fed cut rates. It’s no secret, however, that the $36 trillion national debt is on an unsustainable path, particularly after the lavish spending of the first Trump and Biden administrations.

“The Biden administration’s reckless fiscal policies ran up our national debt and fueled inflation, forcing the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates and borrowing costs for both everyday Americans and the federal government,” White House spokesman Kush Desai said in a statement. “Rising bond yields only underscore the importance of passing The One, Big, Beautiful Bill—the largest spending reduction in nearly 30 years—to get our fiscal house in order and turbocharge America’s economic resurgence under President Trump.”

According to the Congressional Budget Office, the federal deficit for the 2025 fiscal year is $1.9 trillion, or 6.2% of GDP, the deepest shortfall in the country’s history outside of a war or recession.

Extending and expanding Trump’s 2017 tax cuts likely won’t help. The CBO projects the “One, Big, Beautiful Bill” that narrowly passed in the House Thursday will add $3.8 trillion to the deficit through 2034.

A tougher fight awaits in the Senate, where Republican fiscal hawks might have more of a say. Running a big deficit is easier, however, when one party controls Congress and the presidency, Sheridan said.

Markets, he added, are increasingly nervous Republicans will fall into that temptation. Moody’s cited deficit concerns when it became the final major credit agency to downgrade U.S. debt from its top rung of borrowers last week.

Some believe so-called “bond vigilantes” could ultimately force Trump’s hand, though. Since sudden, dramatic increases in borrowing costs can be painful, the theory goes, fixed-income investors can pressure politicians to be more disciplined by unloading government debt.

The role of inflation and U.S. dollar supremacy

Caron, however, doesn’t see rising yields as a momentary phenomenon. Borrowing costs have fallen since the 1980s, he said, in large part because inflation declined and mostly stayed low. He attributes much of that to globalization, with cheaper goods from growing economies like China keeping a lid on prices.

“What we’re seeing today is the exact opposite,” he said.

And that’s not just because Trump has hiked tariff rates to their highest level since World War II.

“It’s more onshoring of manufacturing,” Caron said. “It’s more worry about supply chains from a national-security standpoint.”

Meanwhile, the U.S. borrows at much better rates than its underlying finances would normally allow, thanks to the dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency. Rising debt concerns and a decline in global trade, however, could reduce demand for Treasuries, pushing yields higher.

“There’s a whole host of kind of uncomfortable questions that I think investors are asking,” Sheridan said.

The answers could ripple through the entire U.S. economy.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com