Why Trump and South Africa Are at Odds

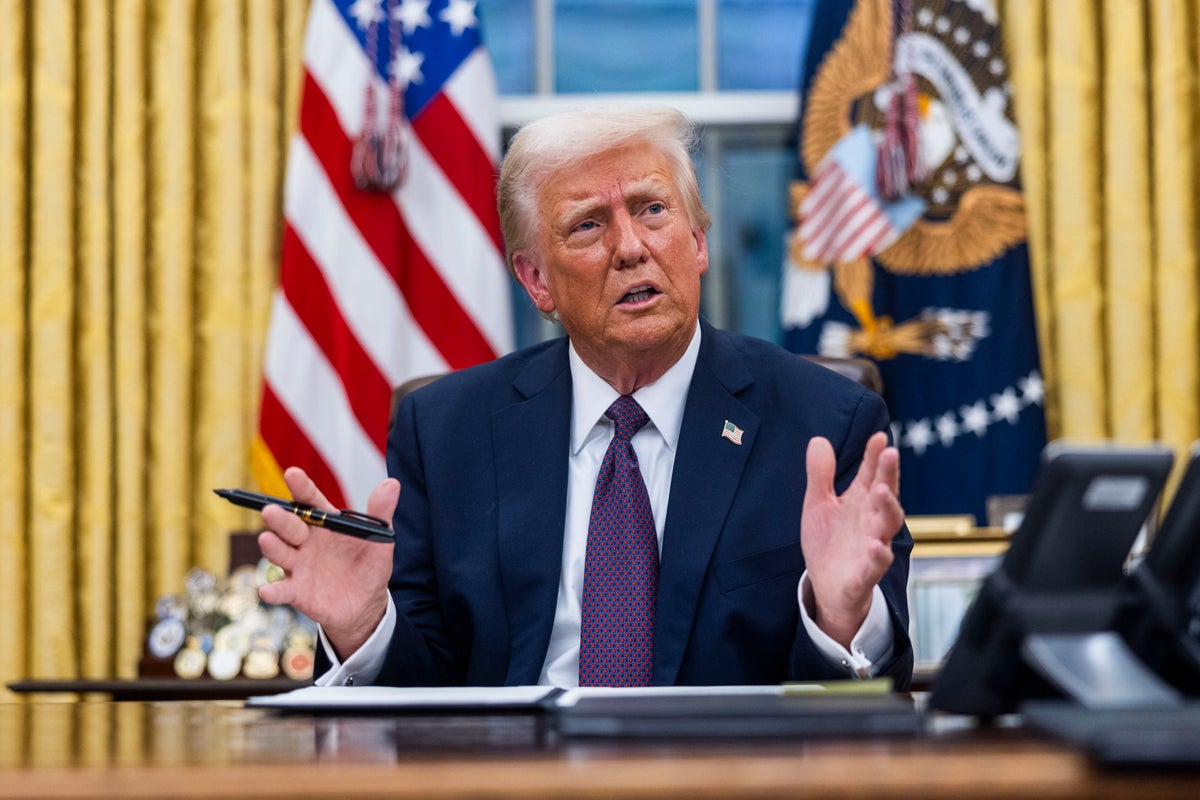

Trump and his allies have targeted South Africa, promoting the false narrative that white people are being mistreated by the nation’s post-apartheid government.

“We will not be bullied,” South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa emphatically told his nation’s Parliament on Thursday.

“We are witnessing the rise of nationalism, protectionism, the pursuit of narrow interests and the decline of common cause,” Ramaphosa said during his State of the Nation address. “But we are not daunted to navigate our path through this world that constantly changes. We will not be deterred. We are, as South Africans, a resilient people.” [time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

While he did not mention any bully by name, Ramaphosa’s remarks came just days after U.S. President Donald Trump threatened to cut all funding to South Africa, alluding to the long-running false narrative that white South Africans are being mistreated by the nation’s post-apartheid government.

Trump and his allies, particularly South African-born billionaire Elon Musk, have ramped up their rhetoric against South Africa in apparent reaction to the recently passed Expropriation Act of 2024, a controversial law aimed at solving the country’s longstanding land ownership inequality problem. The law has drawn criticism for supposedly risking and disregarding private property rights—particularly those of South Africa’s white minority—as it permits land seizures by the state without compensation.

Trump has similarly put “anti-white” policies in the U.S. in his new administration’s crosshairs, cracking down on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI)-related initiatives across the federal government and private sector.

Here’s what to know about Trump’s issues with South Africa.

What Trump and his allies have said about South Africa

On Feb. 2, Trump announced on his social media site Truth Social that South Africa has been “confiscating land, and treating certain classes of people VERY BADLY.” He then said that he “will be cutting off all future funding to South Africa until a full investigation of this situation has been completed.” He later told reporters that South Africa’s “leadership is doing some terrible things, horrible things.”

It’s not the first time Trump has made such claims: back in 2018, during his first term, Trump said he’d ordered then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to look into land seizures from and killings of white farmers in South Africa.

These comments echo a longstanding false narrative pushed by right-wing groups in South Africa that white people are being dispossessed of their lands and are even victims of genocide.

Musk, who was born in South Africa’s Pretoria, has repeated the myth in multiple posts on X throughout the years, including one in 2023 accusing left-wing South Africans of “openly pushing for genocide of white people” and another the same year saying “They are actually killing white farmers every day. It’s not just a threat.”

Ramaphosa rejected Trump’s claims, arguing in a post on X on Feb. 3 that the government “has not confiscated any land.” The South African President said the new Expropriation Act is “not a confiscation instrument” but a legal process that “ensures public access to land in an equitable and just manner.”

Musk responded on X, asking: “Why do you have openly racist ownership laws?” The South African government then said Ramaphosa spoke with Musk over the phone to dispel “misinformation.”

Nevertheless, Secretary of State Marco Rubio posted on X on Wednesday that he will not attend the G20 Summit later this year in Johannesburg, claiming that host South Africa is “doing very bad things. Expropriating private property.” Rubio suggested that to visit South Africa would be to “waste taxpayer money” and “coddle anti-Americanism.”

What is the Expropriation Act of 2024?

The Expropriation Act of 2024 is South Africa’s latest land reform policy aimed to resolve ownership inequality issues created by the pre-1994 apartheid system of white minority rule. Ramaphosa assented to the law on Jan. 23 after five years of public consultation and parliamentary debate.

According to the government, the law “outlines how expropriation can be done and on what basis.” The law allows the government to take in land or “for a public purpose or in the public interest.”

The law mandates generally “just and equitable” compensation, but one clause states that the government may not provide compensation in certain cases, including when land is not in use and the main purpose is appreciation of market value, or when the land has been abandoned.

Under the law, an expropriating authority—an organ of state or person empowered by it or any other legislation—should have first tried to reach an agreement with the land owner or right holder to acquire the property “on reasonable terms.” However, a property can be used temporarily without the need to reach an agreement if it “is required on an urgent basis for public purpose or in the public interest.”

In the weeks since the legislation has taken effect, no land has yet been expropriated.

A history of land ownership inequality in South Africa

Despite the official end of apartheid in 1994, South Africa is still reeling from widespread racial inequality in land ownership.

A 1913 law forcibly removed thousands of Black families from land they owned, limiting African land ownership to just 7%, later revised to 13% in 1936. These quotas largely allowed white people to own large swathes of land, while forcing the Black majority into crowded townships.

Racially-based land measures were repealed in 1991, but, according to economists Johann Kirsten and Wandile Sihlobo of Stellenbosch University, white farmers owned some 63% of land: “The new [post-apartheid] government set a target of redistributing 30% of this within five years. This target date has been moved several times and is now 2030,” they wrote in 2022. But progress has been challenging.

According to a 2017 land audit, white people, who comprised 8% of the population, owned about three-quarters of farms and agricultural holdings, while Black South Africans only owned 4%. Advocates for the Expropriation Act say that’s because, until the new law, the government was only able to buy land for redistribution to Black owners under a “willing-seller, willing-buyer” model, while large amounts of white-owned land remained unutilized.

How has the Expropriation Act of 2024 been received in South Africa?

The Expropriation Act of 2024 was passed before South Africa held national elections last year in which the ruling ANC party lost its majority for the first time since it came into power post-apartheid. While there’s scant public polling on the issue, the Democratic Alliance, the second-largest party in South Africa’s government of national unity (GNU), has opposed the law, saying it “wrongly enables nil compensation in the public interest within the limited scope of land reform and redress but ignores the public interest in economic growth and jobs.” The Freedom Front Plus, a right-wing white party also a member of the GNU, said it will challenge the constitutionality of the law, as it not only “poses serious risks” for South African’s property rights, but also sends “an extremely negative message to the international community” since “investors will not easily be persuaded to invest in a country where their property could be expropriated.”