Forensics Experts Challenged the FBI. So the FBI Tried to Censor Their Conference.

An FBI official urged the American Academy of Forensic Sciences to cancel a conference presentation titled “Taking on the FBI.” The post Forensics Experts Challenged the FBI. So the FBI Tried to Censor Their Conference. appeared first on The Intercept.

The FBI was not pleased. There were mentions of the agency in documents connected to an upcoming forensics conference that it deemed disparaging. So in the weeks before President Donald Trump took office and issued an executive order barring censorship by federal government employees, the FBI set out to do just that.

In mid-December, according to documents obtained by The Intercept, Ted Hunt, a senior policy adviser to the FBI crime lab, approached the president of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences — the nation’s premiere umbrella organization for scientists, academics, and attorneys practicing, researching, and litigating forensic science issues — with complaints and a demand.

According to the documents, Hunt argued that the AAFS should excise certain references to the FBI from two workshops scheduled for the organization’s annual conference, to be held later this month in Baltimore. One of the apparently offensive presentations was titled, “Taking on the FBI.”

In an email memo addressed to the AAFS Board of Directors, the chair of the conference workshops wrote that Hunt also complained about one of the workshop presenters, a former DNA analyst turned defense expert named Tiffany Roy who regularly challenges the work of front-line DNA practitioners working in government labs across the country, including at the FBI. According to the memo, Hunt told AAFS representatives, including its board president, that the agency was upset that Roy would be given any platform at the conference.

If the AAFS failed to take action, sources told The Intercept, Hunt told the Academy brass that the FBI, whose forensics leaders and front-line practitioners regularly attend the gathering, would boycott the organization’s famed annual meeting.

Hunt did not respond to a request for comment. In a statement, the FBI said that the agency “did not make any threats nor consequences” and that it “did not seek to censure any speaker nor have them deplatformed.”

The FBI said that it merely “brought to the attention” of the AAFS material mentioning the FBI that “seemingly violated AAFS’s own bylaws.” Specifically, the agency pointed to a section of the Academy’s Code of Ethics and Conduct that states that no member or affiliate of the Academy “shall issue public statements that appear to represent the position of the Academy” without first obtaining permission from the AAFS board.

It is hard to see, however, how that section could apply to conference materials. The Academy routinely issues disclaimers about the content of conference presentations as not necessarily representing the Academy itself. Moreover, the FBI statement elided the first section of the Code of Ethics and Conduct, which says that every member of the Academy “shall refrain from exercising professional or personal conduct adverse to the best interests and objectives of the Academy,” including to “improve the practice, elevate the standards, and advance the cause of the forensic sciences.”

The workshops at issue had been fully vetted by the Academy as part of its rigorous conference-program acceptance process, and the relevant details already published online. But documents obtained by The Intercept reveal that the AAFS Board of Directors — made up of influential members of the forensic science and legal communities — agreed that their organization should ask the presenters to scrub the offending references to the FBI and that if the presenters failed to do so, that their workshops should be canceled.

At least two members of the Academy leadership went so far as to suggest that the organization should apologize to the FBI for offending it. One opined that he didn’t think Roy, a full member of the Academy, should be allowed to present at all.

News of the incident spread quickly among AAFS’s large but tight-knit community. Some suggested parallels to Trump’s promises of retribution for his, and his administration’s, perceived enemies. The incident has also raised concerns that the Academy, whose vision and mission are to “promote justice for all” and to “elevate the standards and advance the cause of forensic sciences,” would seemingly abandon its critical focus in favor of a position of fealty to the FBI.

The AAFS’s current president, psychiatrist Christopher Thompson, did not respond to The Intercept’s repeated requests for comment.

Within the world of forensic science, the FBI’s laboratory has enjoyed an elevated status as a premiere facility — even though it has simultaneously endured criticism, as past practices in some forensic disciplines have been pilloried in the criminal legal system. In short, the FBI lab is not immune to the issues that have long plagued forensic science writ large. To date, false or misleading forensic evidence has been implicated in nearly 30 percent of the nation’s wrongful convictions.

Many consider standard forensic practices — like fingerprint examinations, ballistics and toolmarks comparisons, or blood pattern analysis — to be foolproof. But these practices were developed by law enforcement agencies for law enforcement, and not by scientists first subjecting them to standard, rigorous testing processes designed to ensure they stand on a solid scientific foundation.

That was the dirty little open secret of forensics in the criminal legal system until 2009, when a groundbreaking report from the National Academy of Sciences laid it bare: With the exception of standard DNA analysis, the report read, “no forensic method has been rigorously shown to have the capacity to consistently, and with a high degree of certainty, demonstrate a connection between evidence and a specific individual or source.”

These criticisms were reiterated, even more bluntly, in a 2016 report from the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, or PCAST, which concluded that so-called pattern-matching practices — where an analyst examines a piece of evidence, say a bloody fingerprint found at a crime scene, and tries to match it to a sample from a suspect — were lacking sufficient scientific foundation. “Without appropriate estimates of accuracy, an examiner’s statement that two samples are similar — or even distinguishable — is scientifically meaningless: It has no probative value and considerable potential for prejudicial impact.”

These and other brutal assessments of long-standing forensic practices hit the community hard. Some practitioners took the findings to heart and quickly set themselves on a path to shore up the foundation of their disciplines. Still others dug in or pushed back — including in the Department of Justice. Shortly after the PCAST report was released, Loretta Lynch, who served as attorney general during Obama’s second term as president, publicly dismissed the concerns raised and recommendations outlined in the report.

A former front-line prosecutor in Kansas City, Missouri, Hunt served on the National Commission on Forensic Science, where he voted against even modest reforms, like reining in language that analysts use in their reports and court testimony to ensure they aren’t overstating the science or the significance of their findings. After assuming office in 2017, the first Trump administration essentially shuttered the NCFS, and instead Hunt was installed as the head of its quasi-successor, the vaguely named “forensic science working group.”

Hunt has remained inside the Justice Department since then. While he occasionally defended the forensics status quo quite staunchly during Trump’s first presidency, during Biden’s term in office he seemed to maintain a much lower profile — at least until the administration’s waning days, when he approached AAFS leadership about squelching negative mention of the FBI in conference materials.

There are two workshops that have apparently offended the oddly sensitive FBI. One, known as Workshop 19, is titled “Unmasking the Evidence: How Defense Experts Prevented Wrongful Convictions.” According to the workshop description, the point of the four-hour session is to “highlight the challenges faced by legal professionals who may lack the scientific background needed to assess forensic evidence accurately” and to highlight the “critical role that defense experts play in preventing wrongful convictions” by scrutinizing the work of the prosecution’s forensic experts.

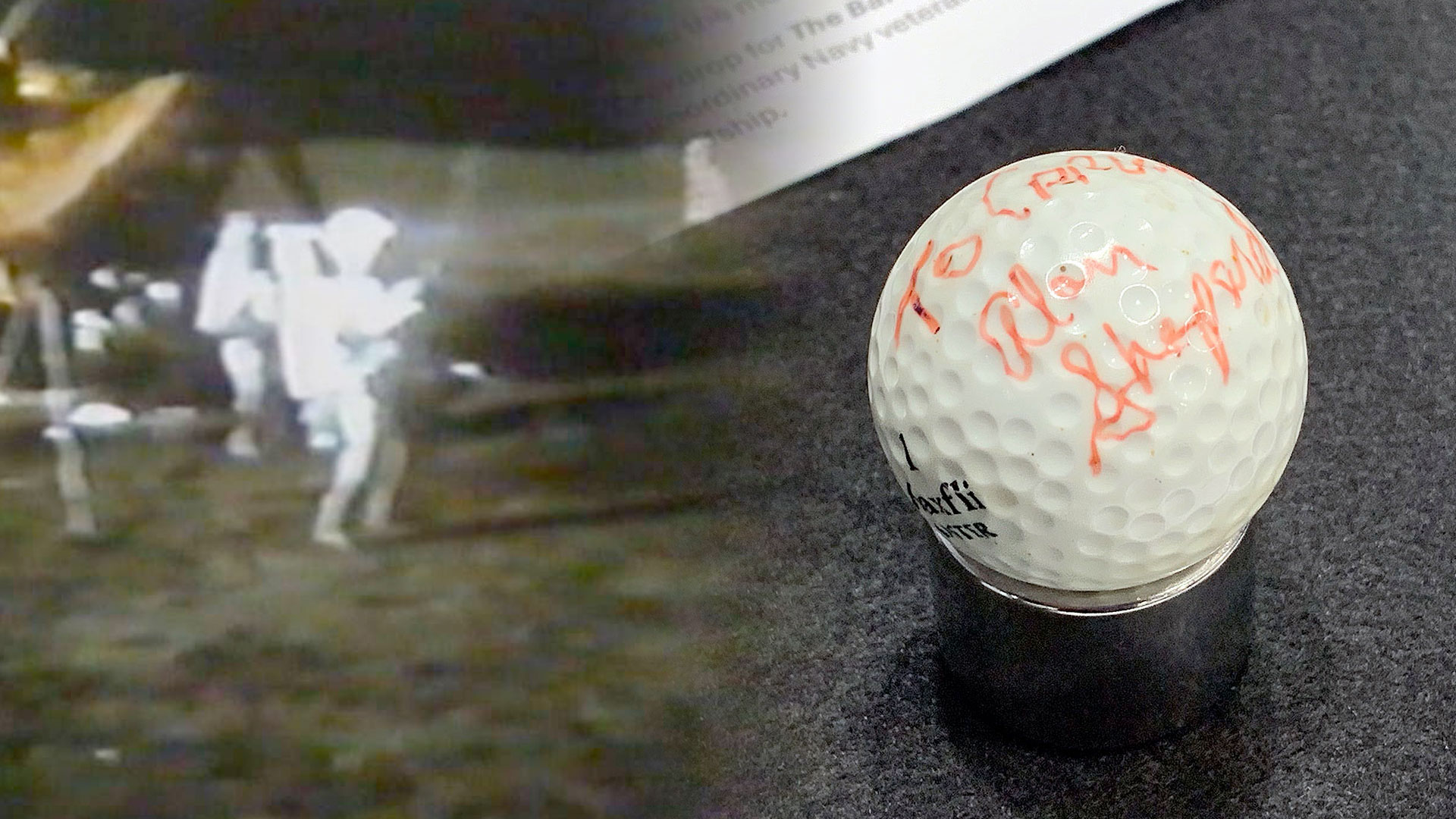

Within that workshop was a scheduled 45-minute talk titled “Taking on the FBI.” Among the “educational objectives” outlined by the workshop organizers was to explore “the impact of prestigious institutions like the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) on perceptions of evidence credibility.”

The second offending presentation, involving forensic document examination and known as Workshop 25, was titled “Death of an ‘Expert’ Witness: Discrediting Document Examiners Who Violate Acknowledged Standards or Binding Laboratory Policies or Who Express Handwriting Opinions With Low Levels of Certitude.” This workshop included an hourlong talk about how the work of a particular document examiner was discredited in a California civil case (the examiner at issue was not an FBI lab employee), along with a separate 20-minute talk titled “How the FBI Has Failed to Enforce Its Own Explicit Standards Applicable to Handwriting Comparison and Improperly Restricts the Use of Blind Verification in Handwriting Cases,” to be delivered by D. Michael Risinger, a veteran law school professor and expert in evidentiary matters.

According to an email memo to the AAFS board by Kevin Kulbacki, a document examiner and the chair of the Academy’s conference workshop committee, the FBI contacted the Academy after the workshop program was published to complain about “the content of these workshops and mentions explicitly of the FBI that were not made by FBI staff.” Kulbacki wrote that on December 16, 2024, he and other members of AAFS leadership took a 30-minute call with Hunt to hear the agency’s concerns.

Regarding the mentions of the FBI in Workshop 19, Kulbacki opined that they aren’t even disparaging of the FBI. “It is common sense that prestigious organizations like the FBI affect perceptions of evidence credibility,” he wrote. “This isn’t controversial, and it takes one look at past discredited methodologies and case failures to see this.” The mentions of the FBI in the workshop “are valid criticism that the Academy should welcome as promoting justice for all and integrity through forensic science, even if potentially uncomfortable conversations arise. This is how we, as a field, get better by acknowledging and addressing issues.”

Where Workshop 25 was concerned, Kulbacki acknowledged that the references to a particular document examiner and to the failures of the FBI’s questioned documents unit “are certainly more antagonistic,” and he suggested that perhaps the Academy should ask the workshop organizers to remove the examiner’s name and to retitle Risinger’s talk to omit direct reference to the FBI in favor of the more anodyne “How an organization has failed” to enforce its own handwriting comparison standards.

“The point is that the FBI’s primary concerns are not with the content of the Workshops but with one of the people associated with one of the Workshops.”

However, Kulbacki was also clear that “99% of the specific complaints raised by the FBI” were about Tiffany Roy, one of the organizers of and presenters in Workshop 19. Kulbacki recalled that Hunt complained about something Roy said during the 2024 AAFS conference in Denver — the gist of which was that real forensic science reform would begin once the old guard, so wedded to past ways of doing things, had passed on. Hunt also took issue with comments she’d posted on LinkedIn regarding the questionable testimony of an FBI DNA analyst in a case where she was serving as a defense expert. (The prosecution ultimately decided against having the FBI’s expert testify in court.)

Kulbacki also noted that the “FBI voiced displeasure at Mrs. Roy’s efforts to hold the FBI” to the standards detailed in a new report from the National Institute of Standards and Technology regarding DNA analysis that seek to mitigate the impact of human biases. Roy was a member of the working group that developed and authored the “Forensic DNA Interpretation and Human Factors” report.

The FBI’s specific grievances about Roy were unwarranted, Kulbacki opined. “The point is that the FBI’s primary concerns are not with the content of the Workshops but with one of the people associated with one of the Workshops,” he wrote. “That is not and should not be grounds for a threat by AAFS of content removal simply because they don’t like someone affiliated with the workshop.” (Emphasis in original.)

“This needs to be a far more nuanced decision than giving the FBI their wish carte blanche.”

Kulbacki wrote that workshop vetting is designed as a blind process to keep such biases out of the mix. “By ensuring that reviewers are unaware of the authors’ backgrounds, blind reviews focus solely on the quality, relevance, and rigor of the content, leading to fairer and more objective evaluations.” Both workshops at issue went through this process, Kulbacki wrote. “I am not here to tell you, the Board of Directors, how you should act” on Hunt’s complaints, he wrote but said that he would be “remiss if I, as the Workshop Chair … did not firmly voice that this needs to be a far more nuanced decision than giving the FBI their wish carte blanche.”

On December 17, the AAFS board voted unanimously (with one member absent) to ask the organizers of the two workshops to censor their presentations or face cancellation. Two members of the board also suggested an apology to the FBI might be in order. “This will go a long way in mending fences,” one board member suggested in an email. Kulbacki’s memo — with all its context regarding Hunt’s complaints — was sent to the board in the wake of their vote. It is unclear whether the full board knew all the details before casting their votes, and minutes from the meeting are brief and spare. Still, it appears Kulbacki’s memo did not give the members any pause about carrying out their plan.

In a statement to The Intercept, the FBI denied that it acted to censor or deplatform anyone and said “there was no discussion” of the Human Factors report.

Kulbacki declined to comment. But sources have confirmed for The Intercept that at least one other Academy member on the call with Hunt verified the details of the conversation memorialized in Kulbacki’s email.

The situation infuriates Andrew Sulner, an attorney and document examiner who is one of the organizers of Workshop 25. He first caught wind that something peculiar was going on when he received an email from the Academy’s executive director a day after the board vote, letting him know that Christopher Thompson, the organization’s president, wanted to have a “short conversation” with him.

Sulner said Thompson told him that Hunt wanted mention of the FBI removed from Risinger’s presentation to “avoid having a title memorialized in print and online that disparages the FBI,” he recalled. Thompson also suggested that removing mention of the agency “would maintain ‘congeniality,’ but I informed him that congeniality has nothing to do with such a request,” Sulner said. Risinger’s presentation was solely about the questioned documents unit of the FBI lab “and not some other crime lab, and that’s why the FBI should be mentioned in the title,” Sulner said he told Thompson.

“They’re operating as a trade union for prosecutors and law enforcement.”

Sulner said he was appalled to see the organization “buckle under pressure from the FBI — but that’s what they do, and that’s the problem. They’re operating as a trade union for prosecutors and law enforcement,” he said, and less like the scientific organization they’re supposed to be. “It is unacceptable and violates the long-standing educational mission of the Academy, which is to improve forensic sciences by promoting good practices and exposing bad practices, period.”

Sulner and his co-organizer, who is also on the AAFS board, agreed to several small changes to their workshop language, but Risinger refused to remove the FBI from the title of his talk and instead opted to pull his presentation from the workshop. For his part, Risinger said that the incident underscores the main point of his presentation — and the underlying paper on the same topic that he intends to publish this year. Risinger said he’ll be using “the history of this development, that would not allow me to have the ‘FBI’ in the title, in the article that I’m writing as more evidence of the extreme nature of the cultural problem at the FBI laboratory.”

“You’ve got censorship on the one hand and an unwarranted revenge campaign on the other.”

Sulner also takes issue with the complaints Hunt made about Roy. He said that he sees the effort to muzzle Roy as vindictive. “I see the requests to excise references to the FBI and to silence Tiffany Roy as raising two separate issues, both very troubling,” he said. “You’ve got censorship on the one hand and an unwarranted revenge campaign on the other.”

In response to the AAFS vote in favor of Hunt’s complaints, Roy and her fellow workshop organizer, also a former DNA analyst, removed the portion of the workshop titled “Taking on the FBI,” which her co-organizer was slated to present, and tweaked the workshop objectives to remove mention of the FBI.

Still, after learning about Hunt’s personal complaints about her, Roy penned a lengthy email of her own to the AAFS board accusing them, in part, of disparate treatment.

In the run-up to the 2024 conference, Roy had approached Academy leadership with technical concerns she had regarding a particular workshop. Specifically, she alleged that the workshop presenters would be providing inaccurate instruction on an emerging field of DNA analysis, but her concerns were summarily dismissed. In contrast, she noted the board appeared to jump through hoops to address Hunt’s concerns — without ever reaching out to her or her co-presenter. And she noted the irony in their actions regarding the decision to excise the “FBI” from the educational objective in Workshop 19 that references exploring the impact of institutions like the agency’s lab on the perceived credibility of forensic evidence. “You all are putting on a MASTERCLASS on exploring the impacts of prestigious institutions like the FBI and I cannot WAIT to present this series of events during our workshop,” she wrote.

In response to Roy’s email, the AAFS board has offered her 10 minutes to speak during one of its scheduled meetings during the Baltimore conference.

For Roy, the incident also points to another serious flaw in the way forensic sciences are deployed in the criminal legal system: Control over forensics and crime labs is largely left in the hands of law enforcement agencies — like the FBI — with little to no independence, which hinders efforts to ensure fidelity to science comes first. One of the as-yet unfulfilled recommendations of the 2009 NAS report was that labs should exist as independent government entities out from under the thumb of police or prosecutor oversight.

“The actions of the FBI in their effort to silence me as an advocate for oversight underscore the dangers of governmental control of the forensic sciences,” she wrote in an email to The Intercept. “Only when science is independent and objective can it serve truth or justice. Science beholden to an adversarial entity is a pawn in a game with no winners.”

The post Forensics Experts Challenged the FBI. So the FBI Tried to Censor Their Conference. appeared first on The Intercept.