A new book makes the case for putting money supply at the center of the U.S. economy and re-empowering commercial banks

“Making Money Work” argues that policymakers should once again make banks the centerpiece of the financial ecosystem.

In the path-breaking book “Making Money Work,” a pair of leading economists present a manifesto for fixing the financial regime that took America on a careening post-COVID ride through rampant inflation, ballooning values of homes and stocks, and spiking income inequality.

In a rush to reverse course and tame prices, the pair argues, a clueless Fed clamped down much too hard, and doesn’t even know it. To make matters worse, heavy-handed regulation has hamstrung the commercial banking system, slowing the flow of credit just as the central bank’s throttling back. The upshot: These dual, wrongheaded policies are already saddling the U.S. with tepid growth, and could easily trigger an unnecessary, self-inflicted recession.

Their solution: Putting the long-ignored “money supply” at the center of U.S. economic policy. To make that happen, the authors say, Washington must recharge the weakened players that create the flow of dollars––the commercial banks––to move this nation back where we should and can be once again: on a path of stable prices and strong, sustained economic growth.

The authors are Steve Hanke, founder and professor at the Johns Hopkins Institute of Applied Economics, Global Health and the Study of Business Enterprise, and Matt Sekerke, a fellow there. Hanke’s renowned as a hardcore “monetarist” who won the nickname “the money doctor” by advising Estonia, Lithuania, Bulgaria, and Bosnia-Herzegovina on establishing currency boards, and Montenegro and Ecuador on dollarization. Those reforms helped successfully smash inflation and establish stability.

The book is an extremely intensive, data-rich work of economic analysis, and a must read for anyone interested in how our economic policy has gone rogue since the Global Financial Crisis. For this review, I conducted an in-depth interview with Hanke where he cuts through the details, and highlights the broad sweep of his and Sekerke’s template for reform. I also refer specifically to passages in “Making Money Work,” which I read carefully. But unless otherwise noted, the capsule summary of its themes come from my talk with Hanke.

What went wrong?

So what is this book all about? “It’s about getting the money supply back into the game. The Fed does not adhere to the quantity theory of money,” says Hanke. The central bank, he charges, incorrectly focuses only on controlling interest rates. He insists that it’s really growth in broad money that determines the levels of economic expansion and inflation, just as an altimeter regulates the altitude of an aircraft. “The Fed’s been using post-Keynesian models that ignore the money supply and hence put us on a rollercoaster,” he says.

In our conversation and in his book, Hanke argues that the Fed’s easy money policies post-COVID hugely inflated all asset prices including land, real estate, and stocks, and eventually created near-double digit inflation. Those policies penalized the middle class and made the wealthy far richer. “In January of 2020, billionaires held 14% of the wealth in America as a share of GDP,” he says. “Today, it’s 21.1%.”

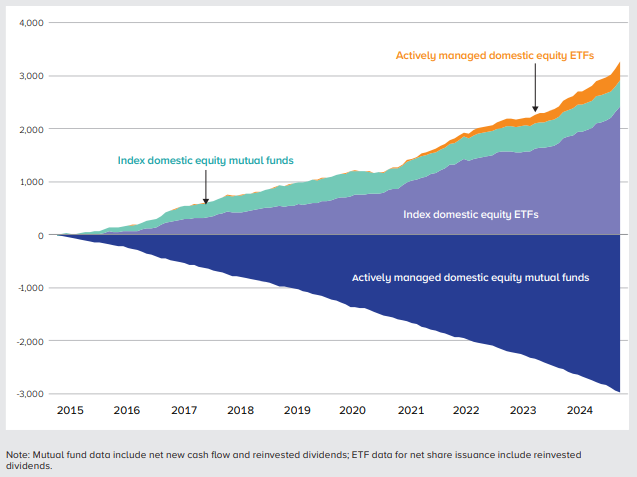

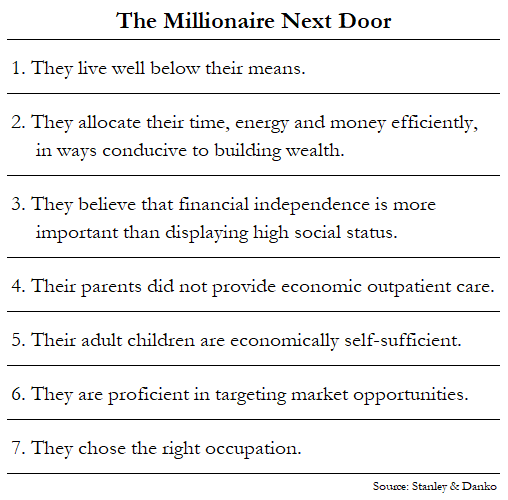

He and Sekerke argue that to get the money supply growing at the correct, steady speed, policymakers need to render commercial banks once again the centerpiece of the financial ecosystem. They point out that these lenders, not the Fed, are the real elephant in the room. About 80% of broad money in the financial system has been produced by commercial banks via their lending to businesses and households.

The book takes a new, holistic view of monetary policy as a three-legged stool. Traditionally, the field’s narrowly focused on the Fed. But Hanke and Sekerke emphasize and integrate the roles of two key players that typically get left out of the picture: bank regulation and fiscal policy. “Bank regulation and the Fed are the two most significant legs,” he adds, with fiscal policy still potentially playing an important role.

Following the GFC, Hanke argues, the rules went haywire on banking. Two reforms hit the banks hard: Dodd-Frank legislation and the Basel III international regime both forced lenders to hold far higher reserves as a cushion. “As a result, the banks became strangled and sharply cut back loans,” says Hanke. After going negative in the months following the GFC, loan growth only gradually recovered, but Hanke and Sekerke argue that it’s still much too low. “Banks are not creating enough money,” Hanke told me. “The growth of their loan books remains relatively anemic, at rates lower than their levels prior to the GFC.”

How to fix it

The authors propose two fixes to get the U.S. back on track for steady prices and steady robust growth.

The first: dismantling the “universal bank” model by “divorcing” the lending business from investment banking. “The rates of return are higher in investment banking than lending, so the capacity to make loans at the universal banks gets sucked away,” explains Hanke.

Second, Hanke and Sekerke avow that Dodd-Frank and Basel III went much too far by imposing onerous “risk weightings” that mandate excessive and discriminatory reserves, on different kinds of loans. “The weightings are too high,” says Hanke. “They’re not fine-tuned. The banks should be given much more leeway in determining the reserves. They know much more about their business than the bureaucrats in Washington and Basel.”

One such regulation that the book contends greatly increased the burden on banks is the “Supplementary Leverage Ratio,” enacted in 2014 as part of the extensive post-GFC reforms. It mandates extra reserves on top of the Dodd-Frank and Basel III requirements that impose relatively high weights for holding even super-safe assets such as Treasuries. Secretary of the Treasury Scott Bessent has called SLR reform “a top priority,” and it’s strongly favored by such banking titans as JPMorgan’s Jamie Dimon. In “Make Money Work,” Hanke and Sekerke assert that the SLR “binds” loan growth, and that reforming it would fit their prescription for unshackling bank lending.

By pursuing policies that undermine and distort lending, Hanke and Sekerke insist, the Fed and Congress are curtailing an overlooked gift embodied in the banking system. When folks invest in stocks, bonds or real estate, that “savings” is channeled through investment banks and other non-bank financial institutions. Those savings are money the investors aren’t spending on consumption––that’s not going to groceries, cars or vacations. But when banks provide credit, as Hanke puts it, “they create money out of thin air” in the form of loans. That money doesn’t come out of new savings that forces investors to forego buying stuff. “It’s the magic no one understands,” says Hanke. Or as the book puts it: “The ability of banks to create deposit money out of nothing is one of the great forgotten facts of monetary economics.”

“The banks act as a type of phantom savers that enable good bankable projects to be financed without having to forego consumption,” Hanke says.

“Making Money Work” writes a new chapter in money and banking, and mounts a compelling case for learning from the post-GFC mistakes, letting the money supply rule by putting the banks back in charge. Because to paraphrase the great bank robber Willie Sutton, “that’s where the money comes from.”

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com